To expand the economy, invest in Black businesses

For the descendants of enslaved Africans in the United States, entrepreneurship represents more than just owning a business and pursuing the proverbial American Dream. Instead, the ability for Black people to participate in local, regional, and global markets represents a dream deferred by systemic racism and discrimination. Consequently, an analysis of Black business ownership can offer insight into the degree to which America is truly the land of opportunity.

Inspired by the work of the Path to 15|55 initiative, this research explores the state of Black-owned employer businesses (hereafter referred to as Black businesses). Using the Census Bureau’s 2018 Annual Business Survey (ABS), which replaced the Survey of Business Owners (SBO), we analyzed data at the national and metropolitan levels to compare Black and non-Black businesses.

The purpose of this research is to provide the empirical context that will make way toward a set of business development goals. Future goals will provide a shared vision among key players that can drive capital to Black entrepreneurs to start, maintain, and grow their businesses. This includes capital from corporations and philanthropies, support from political leaders, investment and products from financial institutions, and venture and startup capital investment from high-net-worth individuals. The potential economic and social returns that strategic investments in Black businesses can have for individual business owners, local communities, and the overall economy warrant an analysis.

According to the most recent Census Bureau data available, Black people comprise approximately 14.2% of the U.S. population, but Black businesses comprise only 2.2% of the nation’s 5.7 million employer businesses (firms with more than one employee).

Black-owned businesses are much more likely to be sole proprietorships. According to the 2012 SBO (the last year reported), 4.2%of Black-owned businesses had employees, compared to 20.6% of white-owned businesses. Black adults are much more likely to be unemployed, and Black businesses are much more likely to hire Black workers. This shortage of Black businesses throttles employment and the development of Black communities. Furthermore, the underrepresentation of Black businesses is costing the U.S. economy millions of jobs and billions of dollars in unrealized revenues.

Fueling Black business growth is broader than just providing capital. It will require leaders in financial institutions, philanthropy, government, corporations, and investors to align and collaborate towards a clear set of goals that address systemic barriers. From supportive policy to representative leadership, it is critical that we work together to build the economy that reflects America’s promise.

Tynesia Boyea-Robinson President and CEO of CapEQ

We have yet to experience an economy that is inclusive. We can’t predict what would happen if the drag of racism was removed from various markets, but if Black businesses posted similar numbers to non-Black businesses, the country would realize significant economic growth. We assume an expansion in the size of the economy such that no gains in Black business revenue or size come at the expense of non-Black businesses.

Introduction

The underrepresentation of Black businesses does not come from a lack of will or talent. Gallup psychologists developed an assessment (Builder Profile 10) to measure the enduring characteristics that predict success as an entrepreneur, including appetite for risk, creativity, and determination. There are no statistically significant differences in performance on the Builder Profile 10 between non-Latino or Hispanic whites and Latino or Hispanic and Black people, according to Gallup’s analysis. Rather, the underrepresentation of Black businesses encapsulates a myriad of structural barriers underscoring America’s tumultuous history with structural racism.

One of the principal barriers to the growth and development of Black businesses is that Black households have been denied equal opportunities for wealth accumulation. The median Black household’s wealth ($9,000) is nearly one-fifteenth that of non-Black households ($134,520), according to our analysis of 2018 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data. Because of historic discrimination in housing and lending, would-be Black businesses owners have significantly less startup capital than their non-Black peers.

According to our analysis of the American Business Survey, 90% of new businesses among all races do not receive any outside investors. Most people use the equity in their homes to start their firms. Prior Brookings research has shown devaluation of property in Black neighborhoods, which throttles this method of business development. Homes in Black neighborhoods across the country are devalued by an estimated sum of $156 billion—the equivalent of more than 4 million firms, based on the average amount Black people use to start their businesses. Declining home ownership rates also hamstring Black business growth.

According to a 2010 Department of Commerce report, “[Minority owned businesses] experience higher loan denial probabilities and pay higher interest rates than white-owned businesses even after controlling for differences in credit-worthiness, and other factors.” Limited access to investment capital in its many forms (e.g., private equity, secured and unsecured loans, philanthropic dollars) is inextricably linked to systemic discrimination in lending, housing, and employment. Past and present housing segregation limited Black entrepreneurs’ access to customers and critical business networks. And the civic infrastructure for business—chambers of commerce, economic development organizations, merchant associations—have long operated along separate and unequal tracks by race.

The COVID-19 pandemic is exposing the painful impacts of structural racism, including Black mortality rates from the virus that are two to three times higher than white rates. COVID-19 does not discriminate, but our housing, health care, and business policies do, influencing neighborhood and market conditions that are correlated with negative outcomes. For instance, the first round of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans (part of the CARES Act, the federal COVID-19 relief package) gave relief only to employer firms. This framework disproportionately excluded Black businesses: 95% of Black-owned firms are nonemployer businesses, compared to 78% of white-owned firms. Additionally, the geographic coverage of the subsidy showed bias. According to a Bloomberg analysis, 27% of businesses in white-majority congressional districts received loans, compared with 17% of businesses in districts where minorities make up more than half the population.

Improving outcomes requires that we remove the drags of racism within various markets. These factors led McKinsey & Company researchers to look at ways to build a supportive ecosystem for Black-owned U.S. businesses.

But nothing grows without investment, which the corporate sector recognizes. Fortune 100 companies are committing billions in the fight for racial equity, and much of that money is open to Black proprietors and businesses and Black-led investment firms. Because racism is systemic and structural, our response to it must be as well.

Establishing a basis for industry and sector goals

In his book Why Leadership Sucks, business writer Miles Anthony Smith wrote, “If you don’t have paying customers, you have a hobby.” Revenue and profit are primary goals for an entrepreneur, so an examination of where money is made is warranted. The highest revenue industries per business are the same for Black and non-Black businesses: wholesale trade, manufacturing, and utilities. That is not to say that these businesses are necessarily the most profitable, but higher revenue generation creates jobs and infuses capital into the communities where these businesses exist.

These categories make up a smaller percentage of Black businesses than of non-Black businesses. For example, the total revenue of Black businesses in utilities—the industry with the highest revenue per firm—is only $85 million. Non-Black utility businesses have a total revenue of $5.6 trillion. This is because there are only 18 Black businesses in the utilities sector. The employment and capital infusion that these types of high-revenue business generate do not exist as heavily in Black communities. Consequently, targeted investments in Black entrepreneurs in high-growth industries are needed for overall community development.

| Total Revenue by industry | Average Revenue Per firm | Black Business Revenue | Non-Black Business revenue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utilities | 93,784,206 | 84,824,000 | 5,596,824,310,000 |

| Wholesale trade | 28,370,415 | 11,809,954,000 | 570,873,420,000 |

| Manufacturing | 22,272,853 | 9,408,794,000 | 8,601,646,746,000 |

Nearly a third of all Black firms in the U.S. are in health care and social assistance fields, and Black women own 54% of these businesses. In contrast, only 11% of non-Black firms are in the health care and social assistance fields. There are a number of economic and social reasons why Black businesses are concentrated in fields different than non-Black businesses—investment capital is one. Businesses in utilities, wholesale trade, and manufacturing (not to mention many tech sectors) require substantial amounts of startup capital, which home equity and individual wealth can’t easily support.

We know large corporates and others have publicly committed many billions to support Black businesses and communities, but most of them aren’t organically connected to Black people or places. The best way to leverage those is to invest in Black-led financial firms with a history and strategy to invest in high growth business led by Black people. This is the delicious low-hanging fruit of U.S. economic recovery.

Stephen Deberry, Founder and Chief Investment Officer at Bronze Investments

| Top Industries for Black businesses | Revenue per firm | Black Firms | Percent of Firms | Non-Black Firms | Percent of firms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health care and social assistance | $3,446,204 | 39,714 | 32% | 619,685 | 11% |

| Professional, scientific, and technical | $2,389,497 | 16,392 | 13.2% | 800,985 | 14.3% |

| Administrative, support, waste management, and remediation | $2,729,916 | 10,136 | 8.2% | 340,401 | 9.4% |

According to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, only 1% of Black business owners were able to obtain loans in their founding year, compared to 7% of white business owners. Black entrepreneurs are denied or given lower bank loans at more than twice the rate of their white peers: 53% to 25%, according to research from the Federal Reserve. When people of color do get loans, they pay higher interest rates on average than white credit recipients: 7.8% to 6.4%, based on a 2010 analysis from the Minority Business Development Agency. Only 1% of funded startup founders were Black, according to the data analytics firm CB Insights.

Research from the Urban Institute demonstrates that Black entrepreneurs’ lack of access to startup capital relative to the resources needed to start a business and lack of access to business networks that inform technical developments leading to industry selection can influence which industries Black entrepreneurs start their firms in. Historically, Black, Latino or Hispanic, and other people of color who owned businesses were more likely to serve a local market than the average for all U.S. firms, restricting the kinds of companies they operate. Black, brown, and Asian American firms are more likely to report that their neighborhood is the site of most of their business transactions, which points to a willingness to serve a community as well as restricted markets.

Public/Private partnerships are key. Relief dollars did not reach the businesses in Black and Brown Communities. The federal government has a role in building capacity among lending institutions that serve disenfranchised business owners.

Luz Urrutia, CEO of Accion Opportunity Fund

Investments can build upon current assets to reinforce industries that have a higher share of Black businesses. The proliferation of Black businesses suggests there is a supportive ecosystem relative to the kind of businesses they operate. For instance, there were about 137,000 barbershops in 2012, according to the most recent data available from the Census Bureau. Nearly half (48%) were Black-owned. That’s more than the number of white-owned barbershops (about 56,000) as well as every other racial group. However, white-owned barbershops employ more people and generate more revenue—about $1 billion more. Receipts for white-owned barbershops in 2012 yielded $1.8 billion, while Black-owned barbershops yielded $800 million.

Building upon strong assets makes sense. Likewise, we must have a strategy to build capacity in industries that show a lower share of Black entrepreneurs. Investments in industries should aim to develop Black entrepreneurs in those sectors as well as the ecosystem where those businesses are situated. A bookend strategy is needed.

Age and size

Black businesses employ fewer people and are younger in terms of their founding date than non-Black businesses, based on our analysis of 2018 ABS data. (See Table 1.) The literature suggests that young businesses are associated with innovation, dynamism, and productivity, but they are also more vulnerable to closure during recessions. Brookings’s Sifan Liu and Joseph Parilla found that small businesses experienced disproportionate job loss during the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. The authors note that smaller firms have more credit constraints and greater sensitivities to consumer fluctuations. Consequently, strategic investments in young firms can help them weather economic storms, improve survival rates, and incite innovation.

| Business Age and Size | Black | Non-Black |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 124,004 | 5,620,639 |

| >100 Employees | 1,587 | 111,308 |

| % >100 Employees | 1.3% | 2% |

| Average number of employees for New firms (Less than two years) | 3.8 | 4.4 |

| Average number of employees for Older firms (More than 16 years) | 17.1 | 53.3 |

| Firms <5 years old | 59,817 | 2,035,733 |

| % Firms <5 Years old | 48.2% | 36.2% |

Black-majority neighborhoods are home to over 3 million business, according to 2018 Census Bureau data. In addition to garden-variety consumer shifts, Black businesses have to deal with consumer declines due to racism. A Brookings analysis of Yelp reviews found that businesses owned by people of color in Black neighborhoods score as high or higher on the consumer ratings platform, but get less revenue as the concentration of Black people increases in a ZIP code. This suggests that customers avoid quality as they dodge Black neighborhoods, costing high-quality businesses upwards of $4 billion a year.

Investments that don’t strategically consider place and sector are not real investments; it’s charity. Black communities and entrepreneurs across the U.S. need investments to reach specific industries in particular regions to maximize growth.

Derrick Johnson, President and CEO of the NAACP.

Highest percentage of Black businesses by metro area

St. Louis has largest representation of Black businesses among the 112 metropolitan areas with data for Black businesses.

Leveraging public and private institutions as guarantors for main street businesses, at scale, is how we build and grow a new generation of businesses and finally close the racial wealth gap.

Nathalie Molina Niño, CEO of O³ and author of Leapfrog: The New Revolution for Women Entrepreneurs

| Top metro areas for Black businesses | Number of Black Businesses | Black businesses percentage |

|---|---|---|

| St. Louis, MO | 6,208 | 10.8 |

| Fayetteville NC | 342 | 7.8 |

| Albany, GA | 172 | 6.8 |

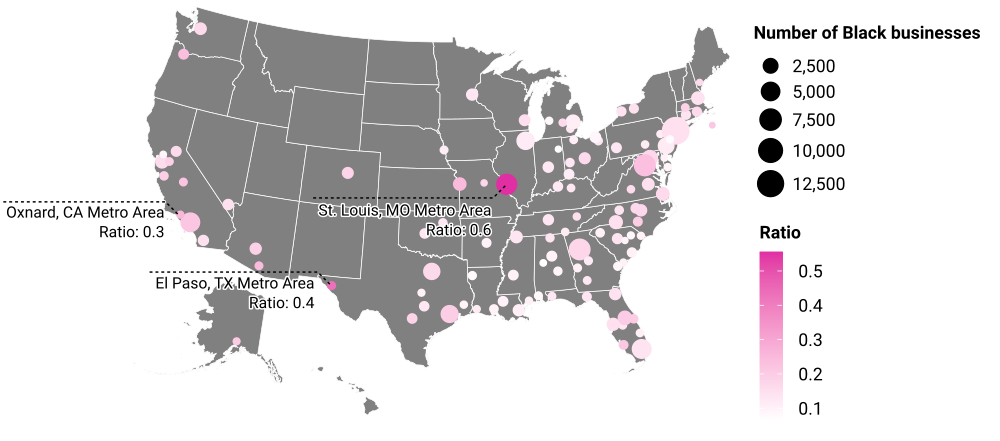

Perhaps a more relevant metric, however, is the ratio of Black businesses to the share the Black population. St. Louis also has highest representation of the Black population reflected in its share of Black businesses. The size of the metropolitan area’s dot is the number of Black businesses and the color of the dot in the map below is the percentage of the metropolitan area’s population that is Black divided by the percentage of businesses that are Black-owned. Therefore, if Black businesses were representative of their population, the ratio would equal 1.0. St. Louis has the highest ratio (0.56), demonstrating that while it is doing the best, it still has ample room to improve.

St. Louis has the best representation of Black population in businesses

Black businesses population representation in business

Note: A ratio of 1 would signify perfect representation. Source: Brookings analysis of 2018 ABS and 2018 ACS data

| Metro areas with highest representation of the Black population | Number of Black Businesses | Black business percentage | Black population percent | Ratio of Black businesses to population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis, MO-IL Metro Area | 6208 | 10.8% | 19.5% | 0.6 |

| El Paso, TX Metro Area | 204 | 1.8% | 4.2% | 0.4 |

| Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA Metro Area | 122 | 0.7% | 2.7% | 0.3 |

Highest average employee pay by metropolitan area

Businesses help communities build wealth across a number of fronts. They provide financial returns for owners and investors, serve the needs of the patrons, and provide wages for workers.

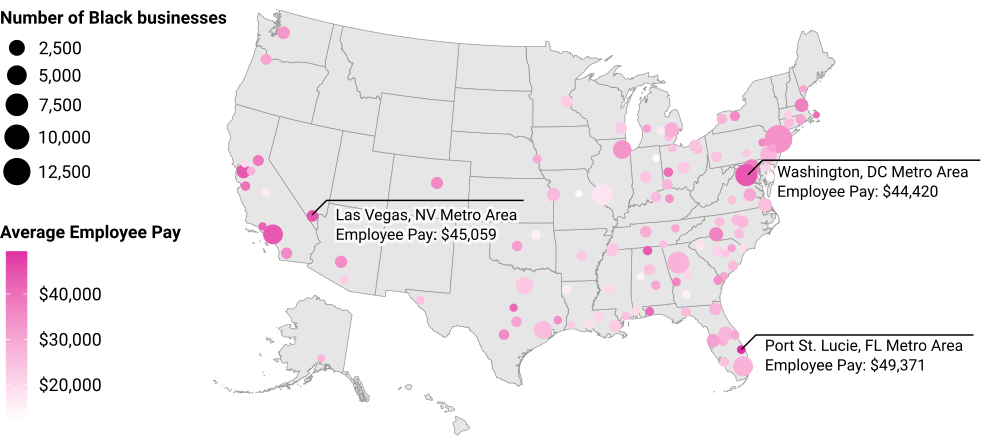

In the map below, the size of the metropolitan area’s dot is the number of Black businesses and the color of the dot represents that metropolitan area’s Black business average employee pay.

Port St. Lucie, Florida has the highest employee pay for Black businesses

Black businesses average employee pay by metro area

Brookings analysis of 2018 ABS data

The metro areas with the highest pay for Black businesses are different than the tech hubs that pay the highest wages for non-Black businesses. The Port St. Lucie, Fla. metro area has the highest average pay for Black businesses, but it only has 158 Black businesses, potentially skewing the findings. Data that tells us the sectors those businesses represent is unavailable for Port St. Lucie—however, nearly one in four (23%) Black businesses there have been in operation for more than 16 years, which is greater than the national average for Black businesses. These older, more established business have greater capacity to increase their payroll over newer businesses.

Similarly, the Las Vegas metro area has only 697 Black businesses. Despite having higher pay, these businesses actually have more employees, with an average of 16. One in four Black businesses in Washington, D.C. are in the professional, scientific, and technical services industry, which is a high-revenue and high-wage industry.

| Highest pay metro areas for Black businesses | Average employee pay |

|---|---|

| Port St. Lucie, Fla. | $49,371 |

| Las Vegas, Nev. | $45,059 |

| Washington, D.C. | $44,420 |

| Highest pay metro areas for non-Black businesses | Average employee pay |

|---|---|

| San Jose, Calif. | $114,881 |

| San Francisco, Calif. | $86,459 |

| Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, Conn. | $77,084 |

The need for business goals

The aforementioned analysis forecasts potential economic gains if Black businesses posted similar numbers to non-Black businesses. Our nationwide analysis assumes the economy can absorb growth in Black businesses without losses in non-Black business. Nationally, the gains in employment, revenue, and overall productivity would fuel an expansion of the economy, lifting all boats. However, different metro areas present varying needs, necessitating nuanced benchmarks. Forthcoming reports will offer benchmarks by metro area.

DBE programs and small business training will never be enough to close the racial wealth gap in America—that’s just tinkering at the edges. We need racial equity standards in the private sector: from greater access to capital beyond traditional debt to new and reparative financial products, from private sector business opportunities to narrative change strategies that center and celebrate Black businesses.

Ashleigh Gardere, Senior Advisor to the President, PolicyLink

Nevertheless, as this analysis shows, there are clear gaps that reveal the general targets for investment or policy change that local, regional, and national actors can rally behind:

Home ownership: Most people start their firms using their personal wealth—most often, the equity in their home. The Washington Post reported that in the first quarter of 2020, 44% of Black families owned their home, compared with 73.7% of white families. (These statistics vary by metro area.)

The devaluation of homes in Black-majority neighborhoods saps critical equity that entrepreneurs use to start their firms. Findings from prior Brookings research show that in larger, more affluent metro areas—or ones in which home values in Black-majority neighborhoods are valued in line with their qualities—businesses in Black neighborhoods tend to receive more reviews and higher ratings. In 2015, the National Association of Real Estate Brokers established the goal of adding 2 million additional Black homeowners—200,000 per year—over the course of five years. This kind of goal-setting is also needed for increases in business development.

Black-owned employer firms in high-growth industries: Black entrepreneurs are underrepresented in employer firms of all types. The aforementioned growth estimates are based on averages among all firms. The growth estimates needed to achieve business equity assume growth in high-revenue industries, which will require a much heavier lift than other sectors. For example, the 2018 SIPP recorded only 18 Black businesses in the utilities sector. The high-revenue industries of utilities, wholesale trade, and manufacturing demand larger sums of startup capital, necessitating a particular strategy to increase the number of Black-owned firms.

Investments in top industries for Black businesses: Investing in top industries for Black businesses makes sense given their relative capacity for growth. Health care and social assistance businesses are particularly primed: The COVID-19 pandemic will continue to take significantly more lives than it has already claimed, and the need for workers and firms in those fields will remain. From the health-tech tools that are developed to the contact tracers hired, investments in Black entrepreneurs represent an opportunity to grow these firms and help the nation through the pandemic.

Place-based investments: The devaluation of housing and businesses in Black neighborhoods warrants a series of incentives for consumer-facing firms and high-growth businesses to operate in Black neighborhoods. Economic activity is concentrating in large metro areas where the majority of Black people reside. St. Louis posts the largest share of Black businesses (10.8%) and the best demographic representation of Black business owners. But for Black businesses to grow, they’ll need higher representation in larger metropolitan areas.

Age and size: The lack of PPP loans to Black businesses exposed the failure of banks to foster relationships with the Black community. To aid businesses’ longevity, closer relationships between Black businesses and banks must be sustained. We need goals to decrease the number of Black businesses and Black households that are unbanked.

Procurement: Setting goals to increase the number of Black businesses that qualify for government and large corporate contracts can accelerate growth among Black firms. Governments and corporations can encourage growth and activity by adopting new procurement processes that facilitate inclusion. For example, Black residents make up a majority of the population in New Orleans, but have been historically passed over in local government contracting jobs. In response, leaders are making commitments to underserved populations: New Orleans’ regional transit authority chose to invest simultaneously in its infrastructure and business owners of color by pledging that a minimum of 31% of its federally provisioned grants would go to contracts with certified minority-owned businesses in the area.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to see our inherent connections in ways that public policy has not always recognized. Individual recovery is contingent upon how much we collectively live by the principle of being “all in this together.” If undocumented residents are sick, the country’s citizens will be as well. If Black and Latino or Hispanic people suffer from COVID-19’s effects, so will white and Asian Americans.

As real as our interconnectedness is in health, so too are we linked economically. Structural racism stifles Black businesses, and we all suffer from an underperforming economy as a result. However, using moments like this one, we can invest our way toward economically inclusive communities.

We can invest in Black businesses, financial institutions, and neighborhoods in ways that combat the spread of COVID-19 and restore the value that racism has extracted. COVID-19 interventions should lead to investments in disenfranchised Black and brown communities, including their entrepreneurs. Similarly, we should be investing in Black businesses to help solve problems in education, transportation, housing, criminal justice, costal restoration, and other fields that show racial disparities.

We must remove the drags of racism while investing with the explicit goal of increasing the number of Black businesses as a return. Inevitable crises will occur. Consequently, we need investment strategies that address the underlying conditions which create racial disparities and undue suffering.