01

The Great Reset:

Relaunching African economies

Emerging stronger: How Africa’s policymakers can bolster their economies during and beyond the COVID-19 crisis

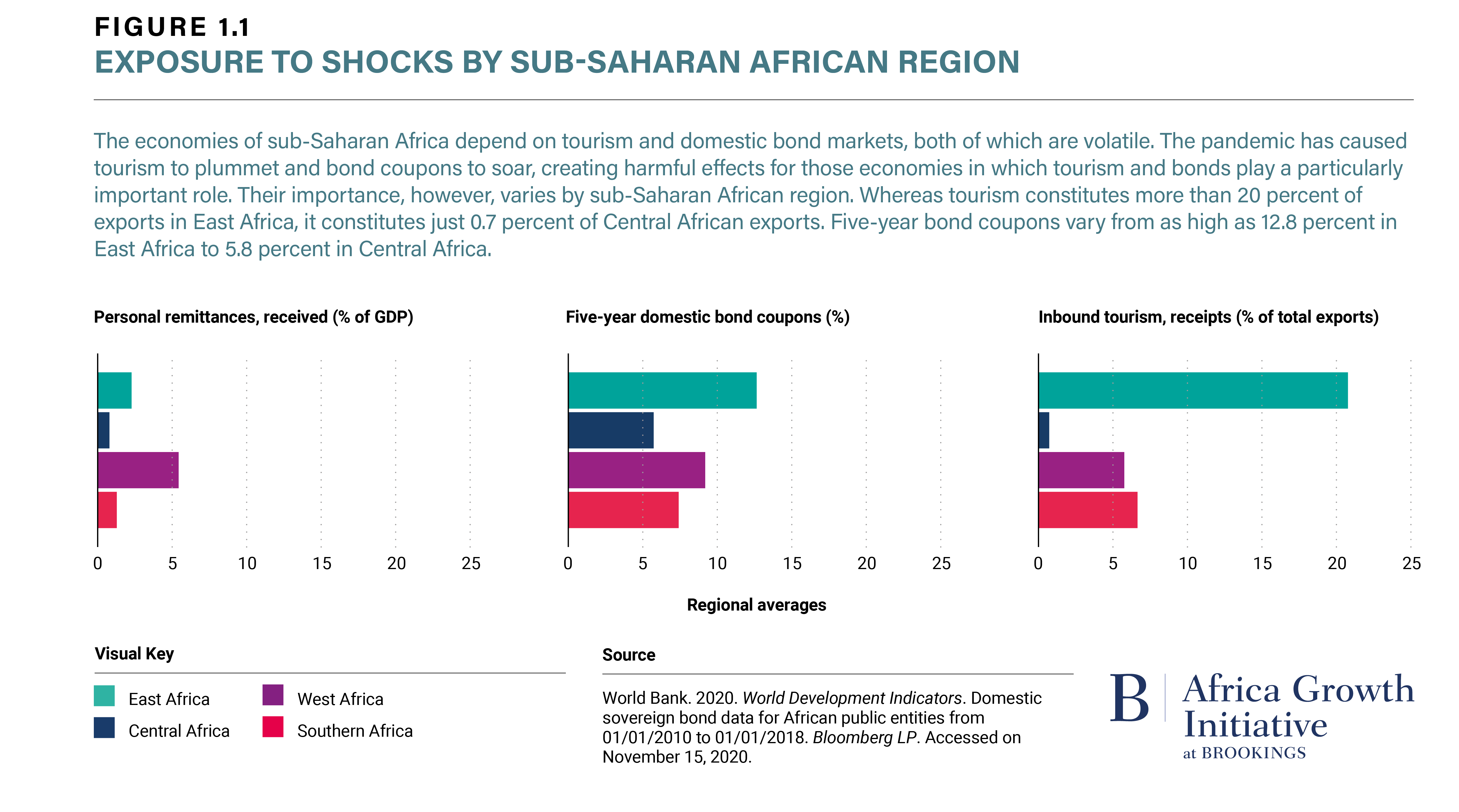

As the world begins to emerge from the economic crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic, the big question in Africa—beyond how do we protect the health of average citizens—in 2021 is how and when Africa will begin its exit from the first economic recession to hit the continent in a quarter of a century. Africa’s economic revival depends on sufficient economic policy response, access to sufficient and affordable financing to recover from the estimated 3 to 5.4 percent contraction in GDP, and strengthened policies for creating jobs. Indeed, Africa’s longer-term economic prospects can be safeguarded by making bold and well-informed decisions today, which, in turn, can transform the current crisis into a catalyst for innovation.

Immediate steps for policymakers

African governments have already spent significant amounts of their GDP on domestic stimulus packages—between 1 and 7 percent. However, the funds made available among African nations for response and recovery are less than 1 percent of the amount deployed among the world’s richest nations. Indeed, under current conditions, sub-Saharan Africa may likely face a financing gap of about $290 billion.

To enable a strong recovery, African policymakers would do well to step up efforts to “stem the bleeding.” By investing strongly and promptly to relaunch economies, governments can avoid an even deeper descent, potentially including debt crises, defaults, and a return to pre-COVID-19 economic levels only by 2030.

How might leaders and policymakers pay for it?

Given the serious fiscal constraints that many African governments face, policymakers need to prioritize where and how to intervene as well as find new ways to attract investment and private-sector participation to deliver critical projects and services. Just as important, emerging opportunities in digitization and data analytics are already improving revenue collection. Now might also be the time to use spending reviews to reallocate budgets to high-priority areas, deliver more cost-effective procurement, and reduce fraud. Across Africa, such public-finance reforms could deliver as much as $100 billion a year in new revenues and savings.

“Bold efforts to mobilize domestic resources can yield rapid results.”

Bold efforts to mobilize domestic resources can yield rapid results. For example, one of the authors worked with a West African country that was able to boost tax and customs revenues by more than 20 percent in just six months. The country rebuilt its customs processes, greatly improving compliance; and it established a debt-collection task force that increased debt recovery from defaulting taxpayers by a factor of five.

That said, African policymakers will also need to redouble their efforts to enlist the global community’s support to strengthen liquidity in the short term and restart growth in the longer term. In the next 3 to 6 months, policymakers should seek increased lending from multilateral development banks; these institutions could potentially use their existing balance sheets to release an additional $100 billion in lending to Africa. Global institutions can also set up a Liquidity and Sustainability Facility (LSF) that would lower governments’ borrowing costs by ensuring that their short-term debt obligations can be met. Such measures would pave the way for the global community to assist African policymakers in restarting and reimagining sustainable growth—for example, by introducing innovative financing tools such as bonds linked to the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Policies for supporting MSMEs must be central to the recovery

At the same time, policymakers must continue to support businesses—both smaller enterprises and larger firms—that have been disrupted by the crisis. Arguably, the greatest priority must be to bolster the micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) that are key to African commerce and account for 83 percent of private-sector employment in Africa.1 Such businesses, which number between 85 million to 95 million, are especially vulnerable to COVID-19 mitigation measures given they are often characterized by person-to-person contact. By just May 2020, 75 percent saw their revenue decline by over 30 percent.

There are several steps that governments can take to provide financial support to MSMEs. One option is to assist MSMEs through larger firms in their value chains, which might include upstream suppliers and downstream buyers. Governments can provide easier liquidity and working-capital terms to these larger players, and they can make such support conditional upon these firms’ providing favorable financial terms to MSMEs. Governments can also consider providing risk guarantees or first-loss mechanisms while requiring banks to on-lend under the chosen set of criteria and guidelines in order to encourage banks to lend to MSMEs.

To bolster large firms, governments can consider two approaches. First, in a few situations, countries may designate certain sectors as “strategic” and develop support packages—potentially including short-term loans, payroll support, and debt-to-equity swaps. In Nigeria, for example, the government has designated key agricultural value chains and the cement industry as strategic; in addition, their broader economic relevance, those sectors are particularly important in the country’s drive to substitute imports. In addition, governments can help a broader set of companies conserve cash and survive the crisis. Options in this regard include lowering the liquidity or capital-ratio requirements of banks assisting companies in raising capital through avenues such as private-equity financing, as well as deferring payments due by companies to public-sector entities. Governments might require companies to maintain a minimum wage or payroll to qualify for such support.

Understanding Africa’s economic challenges in and beyond the crisis

Finance will continue to be one of the greatest needs for African businesses; indeed, only 5 percent of MSMEs across the continent feel they have received adequate support from lenders.2 Provided governments navigate Africa’s fiscal challenges with skill and determination, they can continue offering suitable financial support to small enterprises; in addition to indirect support through value chains and banks, such assistance might include loans, debt forgiveness, low interest rates, assistance with payments to suppliers, and reduction in utility costs. At the same time, policymakers must not lose sight of the region’s informal sector, as 84 percent of African MSMEs are unregistered. Policymakers can take advantage of the opportunity created by the crisis to convince larger numbers of informal enterprises to register, and thus gain better access to finance and markets. Moreover, to promote registration, governments could shape bold campaigns and attractive packages, potentially including multi-year tax holidays and capacity building for MSMEs.

“Instead of attempting to resuscitate all hard-hit sectors, governments would do well to prioritize sectors that can offer services and goods with long-term prospects—and that have true potential for value-creation and employment at scale.”

Governments will also need to make careful decisions about which sectors to prioritize. Instead of attempting to resuscitate all hard-hit sectors, governments would do well to prioritize sectors that can offer services and goods with long-term prospects—and that have true potential for value-creation and employment at scale.

Moreover, mitigating the economic impact of COVID-19 across the continent will require tracking and forecasting the social and political changes that the pandemic has caused, especially as COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated economic hardship and may push up to 40 million Africans into extreme poverty. Policymakers will also need to focus on enabling businesses to respond effectively to these new conditions. In doing so, they would do well to focus on new and existing industries that enjoy high economic potential and a competitive advantage, rather than those that face falling demand, or have been overtaken by businesses enjoying more favorable conditions in other regions.

Technology and the African Continental Free Trade Agreement already show promise for supporting the bounce back

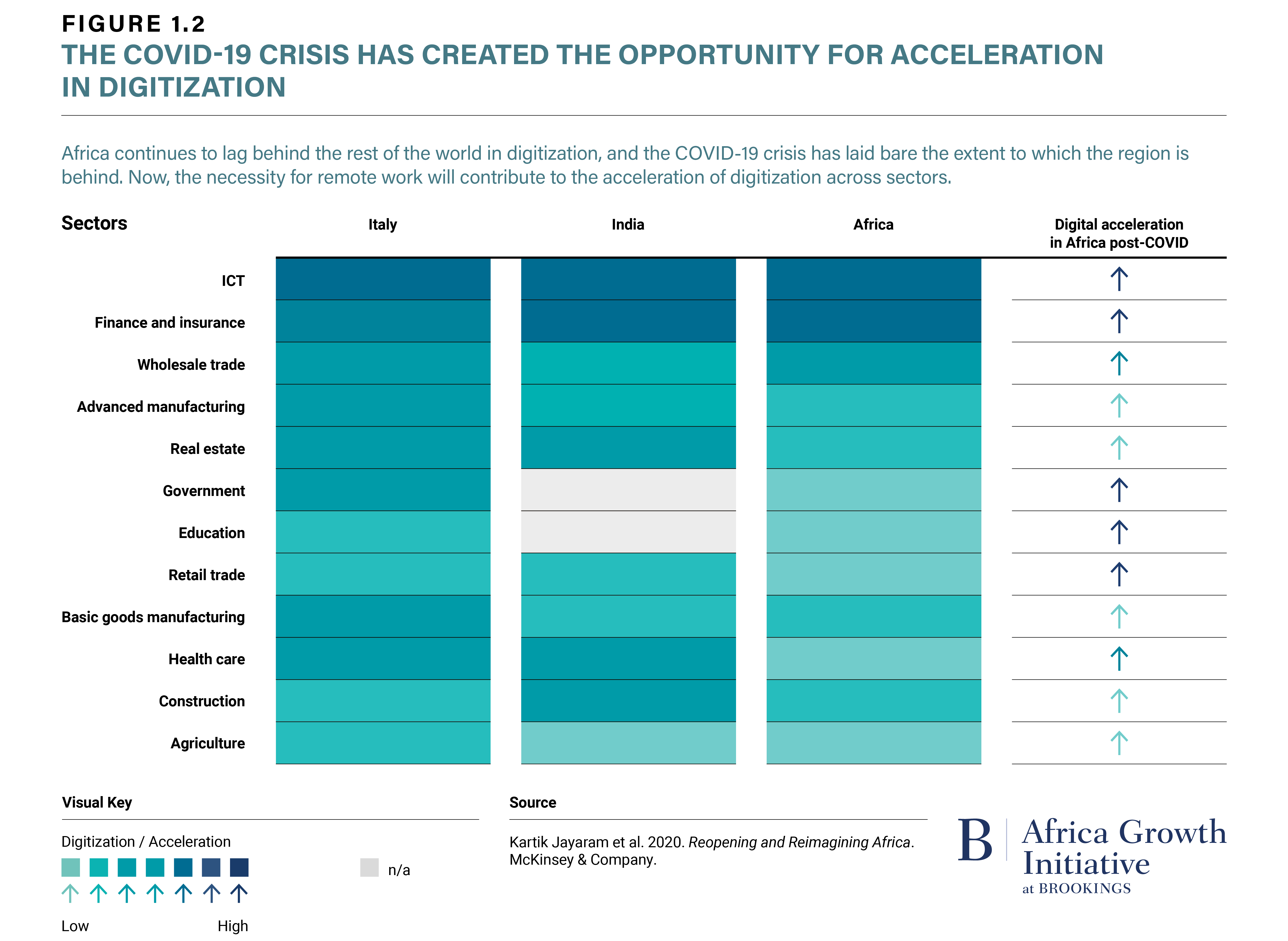

Digital transformation is arguably Africa’s biggest opportunity arising from the crisis. During the pandemic, the continent has accelerated its adoption of ICTs: lockdown conditions have pushed many sectors to raise their online presence and expand their range of digital services, with developments that would ordinarily take years compressed into several months. Significant opportunities remain for digital acceleration in key sectors, particularly government, education, retail trade, and finance (see Figure 2).

Thus, COVID-19 has revealed, more acutely than ever, that leaders should prioritize scaling up investments in the physical and technological infrastructure needed to bring Africa more securely into the digital age and boost the training infrastructure needed to equip the workforce with basic and advanced digital skills, from mobile transactions to graphic design and coding. Leaders can encourage digital practices on the small-scale too in order to encourage widespread usage of digital tools: For example, Kenya and Rwanda have lowered transaction charges in digital payments, thus boosting adoption. Ethiopia recently approved the e-Transactions proclamation, granting legal status to electronic messages and documents.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which also holds promise for accelerating the region’s economies through economic integration and a shift in focus toward high-productivity industrial activities, commenced trading on January 1, 2021. With the increased ease of intra-African trade, African businesses will be empowered to transform continent-wide needs into opportunities for entrepreneurship. (For more on the AfCFTA, see Chapter 4.)

Good, transparent governance cannot be neglected

In this time of crisis, effective and efficient policy implementation at all levels is more important than ever. Governments will need to ensure that support programs are relevant, and that their costs do not outweigh their benefits. Such programs must be accessible, speedily implemented, and scalable. They must be run transparently, under appropriate rules, and managed without conflicts of interest. A key step to improve governance will be to forge a stronger social contract between citizens and the public sector across Africa—around service delivery, transparency, and social protections. (For more on efforts to improve governance in the region, see Chapter 6.) A number of African countries have already committed themselves to enhanced governance over COVID-19-related spending: For example, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Kenya, São Tomé and Príncipe, South Africa, and Uganda have all undertaken independent audits of such spending and published the related procurement contracts.

“A key step to improve governance will be to forge a stronger social contract between citizens and the public sector across Africa—around service delivery, transparency, and social protections.”

Conclusion

The path to more robust and resilient African economies will be a challenging one, calling for boldness, imagination, and tenacious implementation on the part of policymakers. Indeed, a sustained recovery will demand extraordinary effort from public-sector leaders to reimagine policies and practices in rapidly changing circumstances. African governments would do well to focus on profound challenges such as lack of financing – including among informal businesses – and to support promising sectors in order to kickstart and sustain an economic revival. Moreover, leaders should focus on policies and decisions that can have long-lasting impacts, especially around technological adoption and effective implementation of the AfCFTA.

Endnotes

- 1. Findings from a recent collaborative study between AUDA-NEPAD (the African Union Development Agency), Ecobank, and McKinsey & Company (unpublished).

- 2. Findings from a recent collaborative study between AUDA-NEPAD (the African Union Development Agency), Ecobank, and McKinsey & Company (unpublished).