The case for climate reparations in the United States

In environmental and climate change policy, there is a blind spot when it comes to racism. The impacts of climate change are worsening and becoming more frequent: increasingly dangerous storm surges and floods; temperature extremes that raise household heating and cooling costs; and increased exposure to air pollution that causes avoidable deaths, to name just a few. Many believe such impacts to be “colorblind,” affecting all people equally. But they are not.

Enveloped in the term “environmental racism,” communities of color are overexposed to these climate-related harms despite bearing little responsibility for them. From the elevated risk of climate-related disasters that entrench poverty in formerly colonized nations to the disproportionate environmental health burdens in majority nonwhite U.S. neighborhoods, many of these communities are paying a higher price due to legacies of exploitation and devaluation. And because of these uneven distributions in impacts and responsibilities, there is a growing call for a more reparative approach to international climate change policy. The same discussions should also be happening domestically.

Reparations means rectifying past and ongoing harms. As a policy mechanism, it has mostly involved compensatory measures such as one-off wealth or land transfers to individuals impacted by state-sanctioned violence or systematic injustices. Calls for “climate reparations” apply this logic to international disparities in climate change impacts and risks, which are the result of substantial differences in the responsibilities for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, stemming from colonial histories of resource extraction. A parallel logic applies to disparities within countries, particularly in the U.S., where the ongoing legacies of slavery have made many Black communities distinctly exposed or more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

However, the case for climate reparations is distinct from other forms of reparations because of the scale of the impacts and the complexity of determining accountability. Because the impacts of climate change are accelerating (meaning future generations will face more severe and costly risks), what’s needed is not just a wealth transfer to redress legacies of injustice, but a shift toward a more equitable and antiracist climate change policy. That means not just reparations, but a reparative stance.

Defining a ‘reparative stance’ for climate change policy

A reparative stance for climate change policy begins with granting reparations for Black Americans and advancing land reclamation for Native Americans—first as a moral responsibility, but also as an adaptation response to minimize climate change impacts for some of the most vulnerable. But it goes further, aiming to dismantle the structural determinants of inequity that affect Black Americans and other marginalized groups, and that are likely to be amplified in emissions mitigation and climate change adaptation policies without an equity and antiracist lens.

There are historical reasons to pursue climate change policy within a reparative stance rather than similar policy frameworks that are also premised on justice and equality, such as a “just transition,” “new eco-social contract,” or a Green New Deal. For many years, the destruction of the environment has been synonymous with the oppression of people. Environmental destruction and racial injustice have always been interlinked—through colonialism, enslavement, and structurally racist policies such as segregation and single-family zoning. Such wealth-extracting systems have adversely impacted Black communities and increased their vulnerability to environmental burdens. For example, the enslavement of Black Americans transformed the U.S. into the world’s highest-emitting economy and cemented a highly uneven distribution of pollution in the process. As the nation’s most profitable industry at the time, enslavement brought vast wealth to the U.S. economy, which enabled rapid industrial growth and resource extraction. Similarly, the theft of over 99% of Native American land through colonization supplied a foundation for vast wealth accumulation.

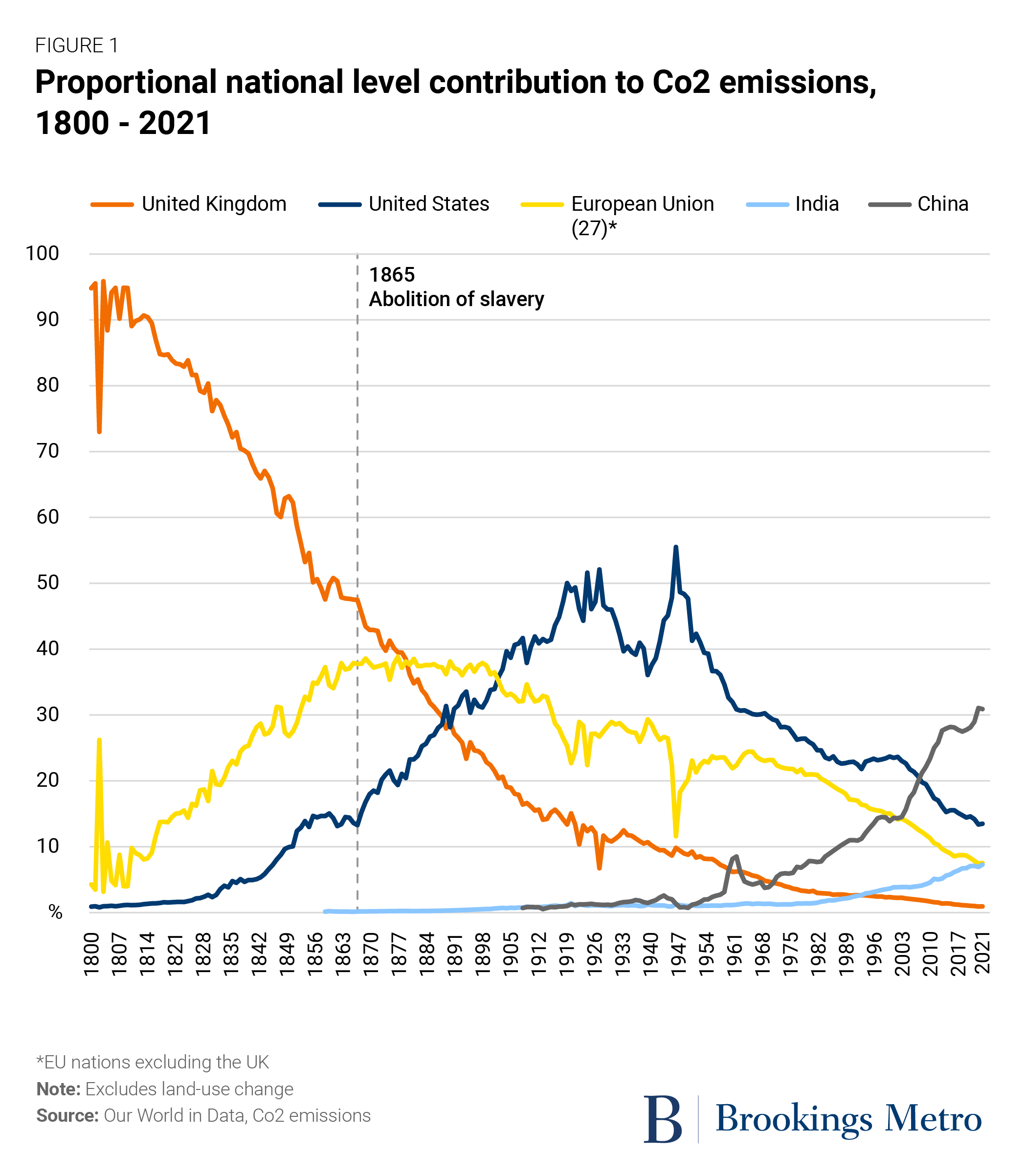

As the systemic exploitation of Black and Native Americans fueled the economic development and prosperity of the U.S., it also spawned environmental destruction. In 1776, the U.S. was responsible for less than 1% of global GHG emissions, but by the time slavery was abolished in 1865 and the Industrial Revolution gained steam, it had grown into the world’s third-highest emitter and was on a rapid course to become the highest by the start of the 20th century.

Many modern policies that determine vulnerability to climate change risks have been shaped by this history with slavery. While some argue that the climate crisis is a universal experience that exposes us all to an increased risk regardless of race, nationality, class, or other characteristics, impacts vary locally. Place-based past and present-day racial discrimination concentrates vulnerability in poorer, nonwhite communities, which lack the wealth, opportunity, and access that contribute to resilience to climate change impacts. The adage “disasters don’t discriminate” may be true, but policy does discriminate—and it is policy that determines vulnerability to climate change impacts.

However, the dial is shifting. After decades of activism led by international Indigenous communities and Global South nations tied to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, historic systems of oppression are finally being talked about in major climate policy forums. At COP27, the most recent international climate policy summit, a coalition of formerly colonized nations and China successfully pushed a breakthrough agreement for colonizing nations to provide loss and damage funding to developing countries affected by climate disasters. The agreement followed increasingly prominent conversations around climate reparations.

Though successive U.S. governments have refused to grant reparations to Black Americans for slavery and state-sanctioned racial discrimination, these shifts in international policy and the looming impacts of the climate crisis warrant revisiting the conversation, as well as what a reparative stance on climate change policy could mean for other historically disenfranchised groups in the U.S. There are not just costs here, but opportunities; structural racism is a wedge that hinders political action on climate change and other social issues. A reparative stance could address these barriers, helping to bridge the country’s racialized gaps as a practical, cost-effective, and—most importantly—just, climate change adaptation and mitigation policy.

As the globe’s largest cumulative emitter, the U.S. also has an obligation to provide moral leadership on climate action. Pursuing reparations domestically is an opportunity to advance the international case for more just—and thus more effective—adaptation and mitigation policies.

International conversations on climate reparations are gaining momentum

In 2022, Pakistan was hit by some of the worst flooding in the nation’s history. Close to 1,300 people lost their lives, and over one-third of the country was underwater. While the damage to lives, livelihoods, and infrastructure was assessed, Pakistan’s climate minister, Sherry Rehman, was clear on the historic injustice of the disaster: “There is so much loss and damage with so little reparations to countries that contributed so little to the world’s carbon footprint that obviously the bargain made between the Global North and Global South is not working.”

The argument isn’t unreasonable. Pakistan is currently responsible for less than 1% of global emissions, and since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the early 1800s, it has emitted less than 0.3% of cumulative global emissions—far lower than the highest cumulative emitters, the U.S. (25%) and the EU (22%). It is the historically wealthy, white, colonizing nations that benefitted (and continue to benefit) from a long history of unimpeded emissions. Despite being referred to as natural disasters, floods, droughts, wildfires, and other impacts of climate change have a structure to them, and that structure reflects wider patterns of injustice.

The magnitude and disparity of impacts like those in Pakistan are a threat to national stability and have motivated the mainstreaming of justice within climate policy. Establishment researchers, government actors, and representatives from nongovernmental organizations view tackling social and racial injustice as a crucial part of effective climate change policy. The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), an organization of world-leading experts responsible for providing the scientific evidence base for policy action, made these links explicit in their 2022 report: “[Vulnerability is] driven by patterns of intersecting socioeconomic development, unsustainable ocean and land use, inequity, marginalization, historical and ongoing patterns of inequity such as colonialism, and governance.”

Informed by this science, international policy organizations are developing lending structures for climate investment that revolve around inclusivity and justice. For example, the World Bank’s Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development model and the International Labour Organization-endorsed Just Transition model connect household-level insecurity—for example, in employment, housing, or wealth—to vulnerability to wider climate change impacts through a rubric premised on justice and inclusivity. Similarly, climate finance innovations such as Barbados’ Bridgetown Initiative advocate for new monetary mechanisms and instruments such as emergency liquidity, which can more effectively respond to intersecting climate, debt, and cost-of-living crises.

Global calls for climate reparations are not dissimilar. Though reparations are novel in environmental policy, they are not an unorthodox solution to inequity, and have been used historically to redress legacies of systematic discrimination internationally and within the U.S. The most straightforward form of reparations is a “settlement model,” which is based solely on financial or land compensation, and has included payments to victims of state abuse, such as Holocaust survivors and Japanese Americans who were forced into internment during World War II.

However, a reparative stance would be closer to an atonement model, which combines wealth transfers with forward-looking policy changes to operationalize equity. A model like this is more likely to prove capable in managing the complex web of social risks stemming from climate change impacts and providing a foundation for climate change policy that can meaningfully address legacies of racist structures.

That’s because climate reparations are as much about moral leadership as they are about financial compensation. Scholars of reparations have focused on the power of a reparative stance—based on connections between slavery and colonialism—to create a lasting transformation for a more just world. Going beyond compensation, a reparative stance should make the complex connections between white supremacy, apartheid, and colonization within climate change policy more explicit—enabling solutions that can address the web of social and economic disadvantage that has left formerly colonized countries more vulnerable. A reparative stance is a process for building new and better policies as much as a solution to prior injustices, involving an iterative cycle that includes reckoning, acknowledgement, accountability, and redress. Ideally, a reparative stance should be about more than a financial transfer to bridge resilience gaps—it is also an opportunity to make amends for prior wrongs and dismantle the policy, health, and prosperity gaps that stem from legacies of injustice that continue today.

Though it is misleading to call the COP27 loss and damage fund discussed earlier “climate reparations” (as it encompasses only future financial impacts of climate-related disasters and does not account for historic injustices), it does take important steps toward a reparative stance. First, by recognizing the differences in responsibilities for the cost of climate change, the fund highlights the unfairness at the core of international efforts to address climate change impacts. Second, by covering slow-onset disasters like sea level rise in addition to rapid onset events like hurricanes, the fund is potentially flexible enough for more existential and cultural claims that explicitly link environmental racism to past injustices, like damages to sacred sites. However, it’s worth highlighting that in its current form, the fund lacks a successful mechanism to allocate accountability and ensure contributions meet needs (multilateral funding is still substantially lower than what is required), which is a crucial aspect of reparations that would need to be addressed in the future.

Nonetheless, the loss and damage fund is arguably the most important instance where these links have been acted upon to date. Despite the EU, U.K., Canada, and the U.S. arguing to avoid reparations language and the responsibility that it entails, the fund is one of the only examples within international policy in which the term “reparations” has been successfully invoked to argue for a policy change.

Tackling these legacies is smart climate policy, but it is also a unique opening to challenge racist structures that persist in policy and undermine climate and racial justice. As founders of environmental racism activism within the U.S., Robert D. Bullard and Beverly Wright are already making these connections between international and domestic racial injustice, ensuring that decisionmakers at COP27 heard the perspectives of fence-line communities of color. Other U.S. climate justice advocacy organizations are also leading a change, promoting racial equity as a crucial lens for successful climate change policy. As U.S. policymakers take on a more prominent leadership position in advancing climate finance and adaptation funds for vulnerable nations, they should be doing the same at home—leading on GHG mitigation and adaptation initiatives that address not only the uneven impacts for historically disenfranchised and marginalized groups, but also specifically the connections between vulnerability to climate change impacts and racism.

Why we should be talking about climate reparations in the US

In the U.S., the ongoing legacies of enslavement and colonization are not peripheral to the climate crisis, but central to it. Black Americans and other disenfranchised groups such as Native Americans suffered under and were restricted from profiting off the exploitative systems of resource extraction and development that propelled the U.S. to become the largest contributor to cumulative GHG emissions internationally.

In some cases, the links to enslavement are explicit. In Louisiana, for example, swaths of land along the Mississippi River were once cotton- or sugar-producing slave plantations; with the abolition of slavery, the petrochemical industry moved in to replace Louisiana’s lost wealth, using many of the same roadways, ports, and other physical infrastructure in addition to some of the same land. Today, the descendants of enslaved peoples there must contend with heavy toxicity and environmental pollution from that industry.

In areas like these, the well-being of communities of color is compromised so that development can happen elsewhere. Black Americans are disproportionately exposed to environmental health risks: They are roughly 75% more likely to live in communities proximate to high-emission or toxic industrial processes, and typically endure levels of air pollution at least 56% higher than what would be equitable. Native Americans have also been subject to processes of “waste-landing,” in which lax planning regulations on Native lands have enabled higher proportions of dangerous developments, including waste dumps and uranium mining.

This environmental racism is perhaps most visible in cities. For example, the legacies of racist infrastructure policies have marooned some Black-majority communities in low-lying areas at heightened risk of flooding or areas with less green space to help lower the temperature of concrete-heavy urban environments and reduce the impact of heat waves. (Because of the latter, Black people swelter through temperatures 2 degrees hotter on average, and 6 to 8 degrees hotter in more extreme cases.)

But it’s not only an unevenness in exposure to climate-related disasters that is driving differences in impacts along lines of race. Vulnerability—a combination of intersecting factors such as wealth and housing security that lower resilience to disasters—is also driving disparities. For example, some less-exposed Black-majority neighborhoods are facing climate gentrification, in which property price increases in higher-elevation areas are driving low-income residents out. Additionally, many Black communities have been blocked from building wealth and are navigating the impacts of the climate crisis without a safety net. On average, Black families have roughly 10 times less wealth than white families, and experience place-based disadvantages such as poor access to adequate health care that accentuate climate risks. For a low-income household that lacks a financial safety net, a climate impact like a heat wave can put them in an unenviable position of choosing between financial risks or health risks—i.e., spending money on cooling versus suffering through dangerous heat. Similarly, both sudden disasters and gradual climate changes can affect employment opportunities, earning potential, and household debt, which can widen preexisting wealth gaps.

Finally, climate funding without a strategy that considers racism is likely to replicate or even increase racial wealth and prosperity divides. This is tied to the valuation of properties and other assets, not just access to asset building in the first place. Take real property: After major climate-related disasters, majority-white communities tend to see wealth growth, including increased property values of up to $126,000 due to renewed investment. Yet Black-majority communities see wealth declines of up to $27,000. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the largest provider of disaster recovery funds, is rife with racial inequalities: Black households receive less compensation on average due to bias in housing appraisals, and a complicated review process means they are also less likely to mount an appeal. Indeed, Black-majority households are more likely to accept buyouts, meaning increased potential for post-disaster displacement and community collapse.

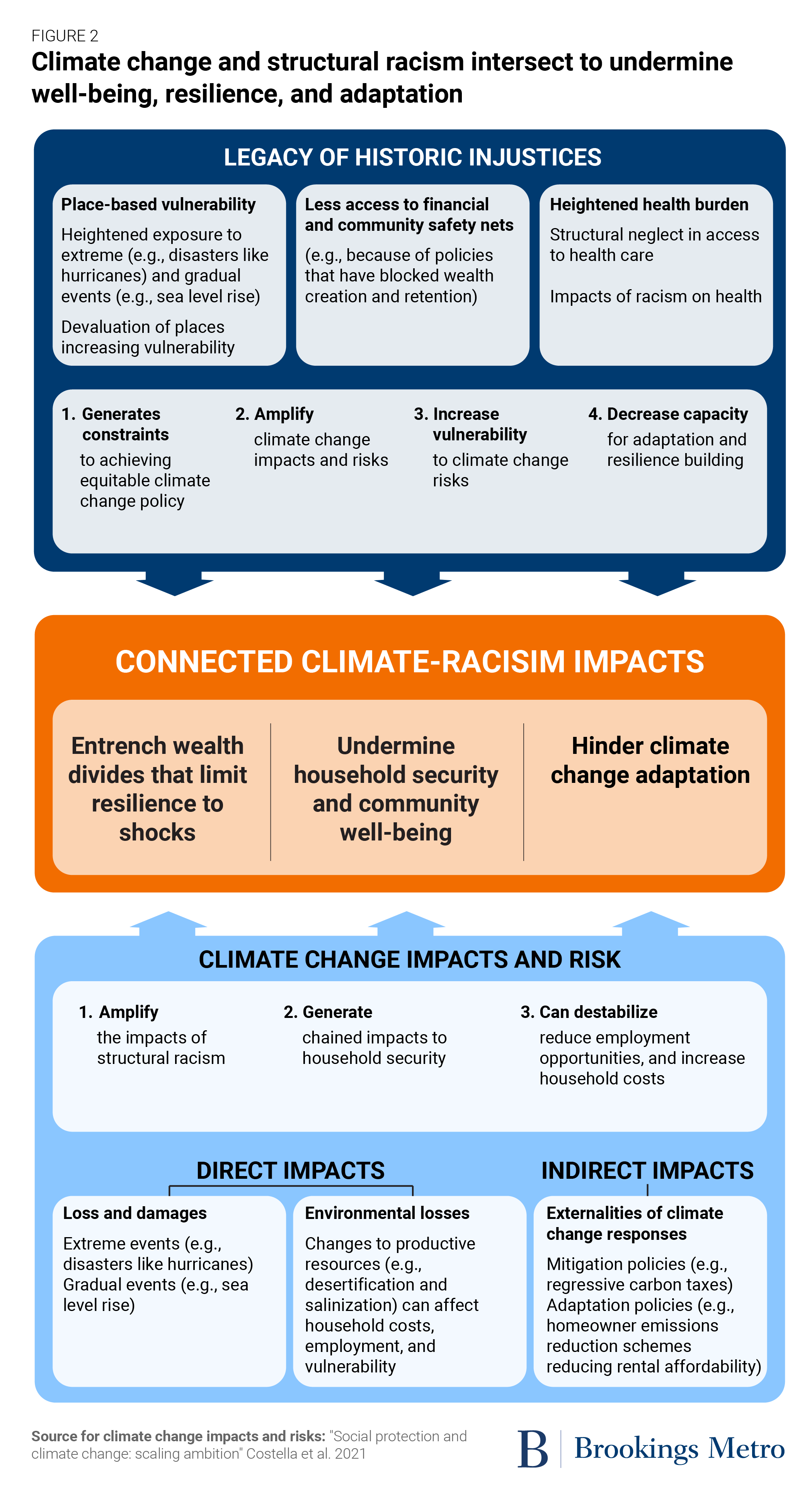

These stark, place-based, racialized disparities show that international and domestic contexts share more similarities than differences. At the international scale, entrenched poverty and structural inequalities drive differences in vulnerability and adaptive capacity between nations along lines of historic wealth extraction, creating a unique poverty-climate context which obstructs well-being and warrants a more just approach to climate change policy. Domestically, structural racism drives vulnerability, generates constraints to equitable climate change policy, and amplifies climate impacts and risks. Both scales underscore the importance of reckoning with racist legacies for ameliorating climate change impacts and advancing a more equitable approach. Figure 2 visualizes these connections, building off common international frameworks that visualize the chained impacts of climate change to think about how racism and climate vulnerability intersect.

Over the past 20 years, international governments’ failure to commit to funding targeted adaptation has widened climate impact disparities. And in the U.S., the federal government’s failure to redress the ongoing exploitation of Black communities makes our governing structures complicit in the uneven distribution of environmental harms. The Biden administration’s climate policies, such as the Inflation Reduction Act and the Justice40 Initiative, need to take a more active and targeted stance to remedy these disparities and offer moral action to kick-start more equitable policies.

Principles to guide a reparative stance for US climate policy

A reparative stance in climate change policy means pursuing racial justice and equity in mitigation and adaptation policy, both at the individual and community level. It starts with wealth transfers to redress the egregious injustices of slavery and colonialism, as these structures were instrumental in shaping the uneven distribution of climate change risks and vulnerabilities. It continues by scoring decarbonization and GHG mitigation policies for equity impacts before decisions are made, to guarantee that investments don’t just reduce aggregate emissions, but also spread wealth across historically disenfranchised communities. Finally, adaptation policy that is localized and prioritizes community wealth and health is also crucial to avoid “colorblind” approaches that can worsen inequality despite national-level improvements.

At least two questions complicate the case for domestic climate reparations and underscore the importance of considering the scale of impacts and policy solutions. The first concerns equity. What “equity” means differs across communities and the intended scale of outcomes. For example, the international loss and damage fund centers around accountability and fairness in access to funds, but a domestic stance should also consider more localized concerns, such as inclusion in decisionmaking and questions of ownership, which would help to ensure that gains in equity are not diminished over time. These are important questions that need to be addressed; differences in how equity is framed changes how it is measured, and thus how solutions are operationalized.

The second concern is determining accountability. Perspectives vary on whether national governments or high-emitting corporations should fund emissions reduction and adaptation, such as through windfall taxes. This is further complicated by the multiple levels of domestic governance—federal, state, county, city—that can sometimes obfuscate responsibilities to take action. But they have also proven successful at pushing for progressive climate policy and conversations on reparations where the federal government has failed.

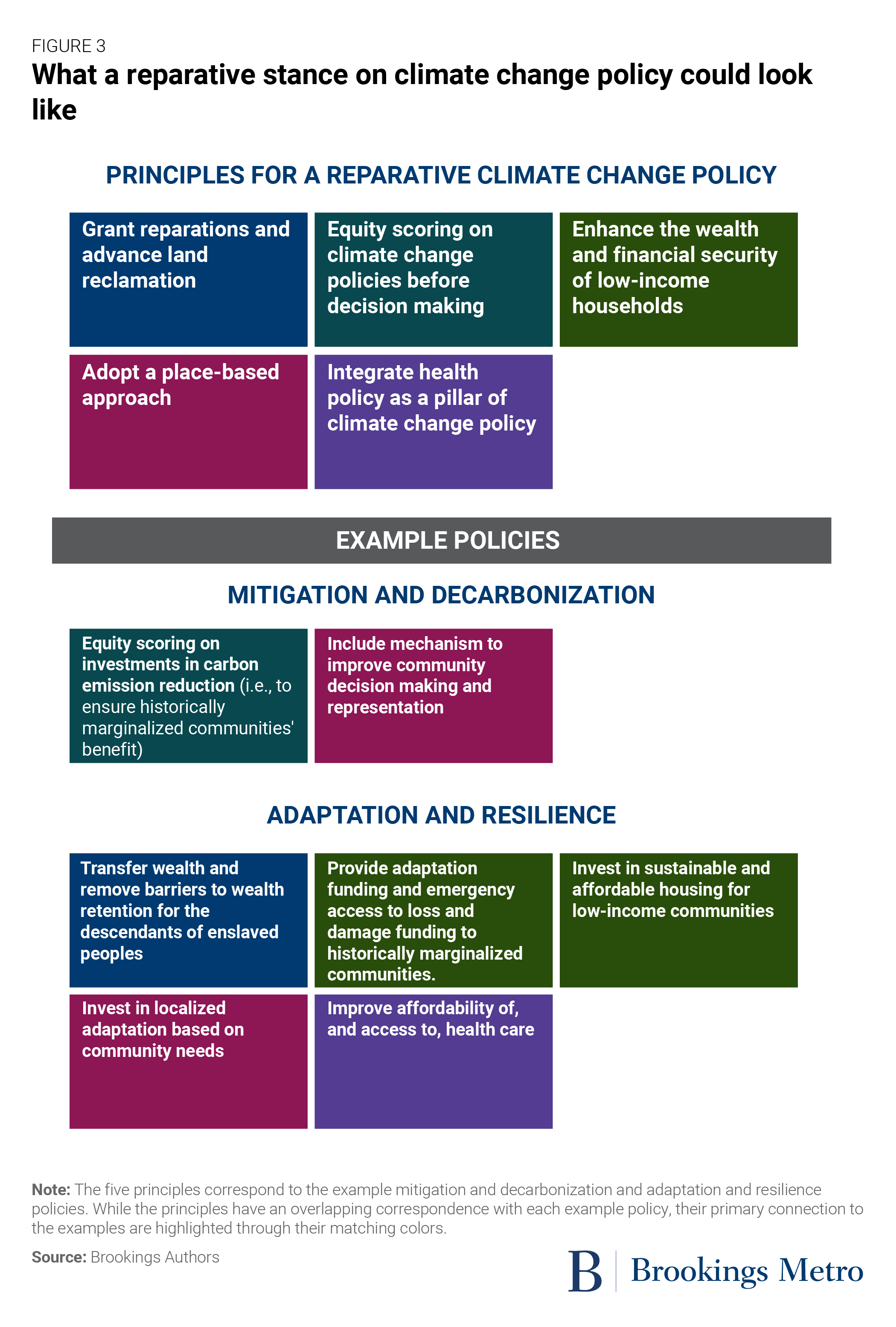

However, questions like these and others concerning operationalization are perhaps premature. What’s more immediate is acknowledging this legacy of racial injustice in climate change impacts and taking steps to act on international momentum in climate justice. To that end, what follows are several principles to guide a reparative stance: 1) grant reparations and advance land reclamation; 2) score equity outcomes in climate change policy; 3) enhance the wealth and financial security of low-income households; 4) adopt a place-based approach; 5) integrate health as a climate change policy. Visualized in Figure 3 and discussed through examples below, we explore how these principles could work through adaptation and mitigation policy, situating reparations as an antiracist climate change policy that would help bridge wealth and prosperity divides while building household and community resilience.

Grant reparations to the descendants of enslaved peoples and advance land reclamations for Native Americans

Wealth transfers and policies to level the playing field in access to education, homeownership, lending, and ameliorating debt should be central to climate change policy. Racial wealth gaps largely determine the severity of climate-related disasters on households. By decreasing wealth inequality, reparations would reduce the risk burden of the most vulnerable communities. Likewise, the removal of financial barriers to access education, for example, would increase household resilience while creating an environment where climate change adaptation is more likely to be successful. Advancing land reclamation for Native Americans could also ameliorate climate impacts; around the world, Indigenous peoples conserve 21% of the world’s land, protect 80% of its biodiversity, and sequester a substantial amount of carbon.

In addition to being an opportunity to show moral leadership on climate change policies, reparations are also smart, efficient adaptation policy. Contrary to opinions that question the value of reparations, mechanisms that bridge inequality also help to lower the cost of climate change impacts, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates have cost the U.S. $2.3 trillion in physical damages since 1980. The true cost—including increased health care burdens, lost wealth, and transitional impacts on households and communities from decarbonization and GHG mitigation policies—are likely to be much greater. Reparations are an investment in people and communities, and if implemented correctly, could be a relatively cost-effective mechanism to lower the total economic impacts of climate-related disasters, slow-onset events, and the impacts of climate change policies themselves.

Score equity outcomes to guide investments in mitigation and decarbonization

History shows that if racial equity is not part of the conversation, policies are more likely to have uneven outcomes that inadvertently or intentionally reproduce racial divisions. Climate spending on emissions reduction is also not guaranteed to deliver positive—let alone fair and equitable—outcomes for all communities. But the broader risk is not yet widely acknowledged: A failure to bring equity into the conversation before investments are made risks transitional policy becoming another vessel that widens rather than reduces racial disparities.

The Biden’s administration’s Justice40 Initiative (a commitment to ensure that at least 40% of the overall benefits of federal climate action flow to historically marginalized communities) and other targeted regional and metropolitan programs are making progress in this regard. But these initiatives only go so far; they fail to codify equity considerations into a broad climate policy response that would help drive, for example, massive investment of public funds for infrastructure. For instance, while the federal pathway to net-zero emissions will theoretically benefit communities of color, the proposal fails to deliver an overarching strategy to do so. This is at least partially why infrastructure investments such as the proposal to widen the Newark Bay Turnpike through Hudson County, N.J. are continuing to promote decisions that over-burden communities of color and are likely to lead to net increases in emissions. Moreover, early evidence from climate infrastructure spending targeted at low-income communities has demonstrated inequities between Black-majority and majority-white communities in the allocation of precious public resources.

Thus, it is imperative that emerging GHG mitigation policies create opportunities for the most affected communities and do not replicate regressive models. California’s cap-and-trade GHG emissions market—which aims to reinvest 35% of auction proceeds into building low-emission and affordable housing—is a good example of how this could be achieved (though they target only for income and not race or ethnicity). Climate change policies present not just an opportunity to redress inequities, but also to score projects for distributional impacts before decisions are taken. In 2021, the city of Chicago did just that, producing the country’s first racial equity impact assessment, which is helping to ensure that the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program delivers positive outcomes for marginalized populations and neighborhoods. Other policies that address housing security and safety, such as Pennsylvania’s Whole-Home Repairs program, are having reparative impacts without an explicit climate change framing, illustrating the ways that more holistic approaches can also contribute to ameliorating climate change impact disparities.

Enhance the wealth and financial security of low-income households as part of climate change adaptation

When it comes to climate action, reducing carbon emissions continues to garner most of the attention and resources. But we need to do much better at prevention: minimizing the tremendous costs of climate-related disasters and improving the supports that help people to adapt and become more resilient to climate shocks. This is especially importantly for Black people and communities because of their history of forced segregation, asset stripping, and imposed vulnerability.

U.S. adaptation policy has primarily focused on disaster response and preparedness. While crucial, this often fails to address the second- and third-order impacts of climate-related disasters, such as income loss, unemployment, and housing instability. Moreover, gradual changes such as sea level rise and increasing temperatures also threaten household stability by increasing power, transportation, and health care costs and reducing employment opportunities.

These secondary impacts amplify the direct costs of climate change both for households and the nation, and can undermine successes in reducing poverty and inequality. Thus, to ensure that reparations create lasting change, improving financial resilience through access to loss and damages funds and adaptation funds should be central to climate change policy.

Invest in localized adaptation, especially in Black-majority neighborhoods, to build community resilience

If we value Black people, we should also value Black places. When communities are valued and invested in, they can become safer, more livable, and more environmentally sustainable places. For example, the regions where Black people are performing far above average in terms of life expectancy are correlated with greater household and community wealth and better environmental conditions. It follows that policies bridging place-based wealth and prosperity disparities are crucial to addressing uneven climate impacts.

Disadvantaged communities are not just vulnerable—they can also drive climate action. Federal funding should empower local leaders and community members to spearhead adaptation efforts that directly respond to their needs. With only $1 of every $7 spent on climate change policy allocated toward resilience, we are treating the symptoms but not the causes of climate vulnerability. This is partially why counties that receive FEMA grants tend to need them again. A localized, preemptive approach that incorporates equity all the way down—through projects and the processes by which they are implemented—can ensure that climate impacts do not entrench inequalities in place, and thus along racial lines.

Integrate health policy as a pillar of climate change adaptation

Climate policy is health policy, affecting both the social and environmental determinants of health. Failing to take these connections seriously impacts everybody, but especially undermines well-being in Black communities, where the health impacts of the climate crisis are more severe and health policy gaps are already substantial.

Thus, ensuring equitable access to affordable health care should be thought of as part of well-rounded federal climate policy. This includes continued efforts to lower the cost of health care for vulnerable groups, expand insurance coverage, and improve the environmental conditions of neighborhoods—first to decrease risk factors such as exposure to heat waves and poor air quality, but second to remove barriers to healthy lifestyle choices (the behavioral dimension of health and wellness) such as limited access to parks and healthy food.

We need a reparative stance for climate change policy

The United States needs a reparative stance for climate change policy—one that not only addresses the uneven vulnerability to climate impacts that exist along lines of race, but that also reduces the discrepancies in racial wealth, health, and prosperity gaps; ensures equity in the opportunities that stem from climate adaptation; and protects investments in emissions reduction from becoming another vehicle for disenfranchisement. This starts with recognizing the role that exploitation has played and continues to play in climate change and its environmental impacts.

International policy is rapidly catching up, highlighting the relationship between inequality and climate change policy with mechanisms that link contemporary impacts to historic injustices. To ensure that climate policy is not undermined by racial injustice, America’s domestic policy should do the same.