KNOW YOUR PARENTS

Between May 2020 and January 2021, the Center for Universal Education at Brookings, together with its Family Engagement in Education Network project collaborators, surveyed close to 25,000 parents across 10 countries on families’ beliefs, motivations, and sources of information with respect to their children’s education. This brief shares the insights and key takeaways, including:

- Most parents desire a “new” type of education for their child that is interactive and social in nature and supports both their socio-emotional and academic development.

- Teachers play a central role in shaping parent’s beliefs about what makes a quality education.

- Education decisionmakers must get to know the parents in their jurisdiction to build strong family partnerships and navigate change.

Introduction

Until the COVID-19 pandemic, the global education community spent relatively little time thinking about the role of parent engagement in education. But when almost all the world’s countries shut their school doors last March, engaging parents and families moved quickly to the top of the agenda.

Who’s considered a parent?

Throughout this brief, we use the terms parent, primary caregiver, and family interchangeably to describe the adult responsible for caring for a child.

Research confirms that a trusting relationship between families and schools has always been important. A meta-analysis across 50 studies on the impact of family engagement in education showed that effective parent engagement strategies that transform parent involvement into parent-educator partnerships have a significant positive effect on children’s academic and socio-emotional development.

Building partnerships between communities and schools is particularly important for navigating education change, something the global pandemic has illuminated. In the United States, for example, while many schools struggled to establish connections with families after school closures, some—like community schools with strong relationships to families prior to the pandemic—were able to rapidly pivot to meet student needs when school doors closed.

But most importantly, parents’ and families’ perspectives on what makes for a quality education for their children deserve to be included in the debates about improving or even transforming education to meet their children’s needs. Parents themselves are eager for a deeper partnership with teachers and schools coming out of the experience of remote learning during COVID-19. In a nationally representative survey, 60 percent of American parents said they were likely to try to develop a stronger relationship with their child’s teacher than they previously had. Around the world, parents and families have emerged as essential education allies amid the pandemic, and developing effective ways of partnering with them that neither ask too much nor expect too little has the potential to not just improve schools but transform entire education systems.

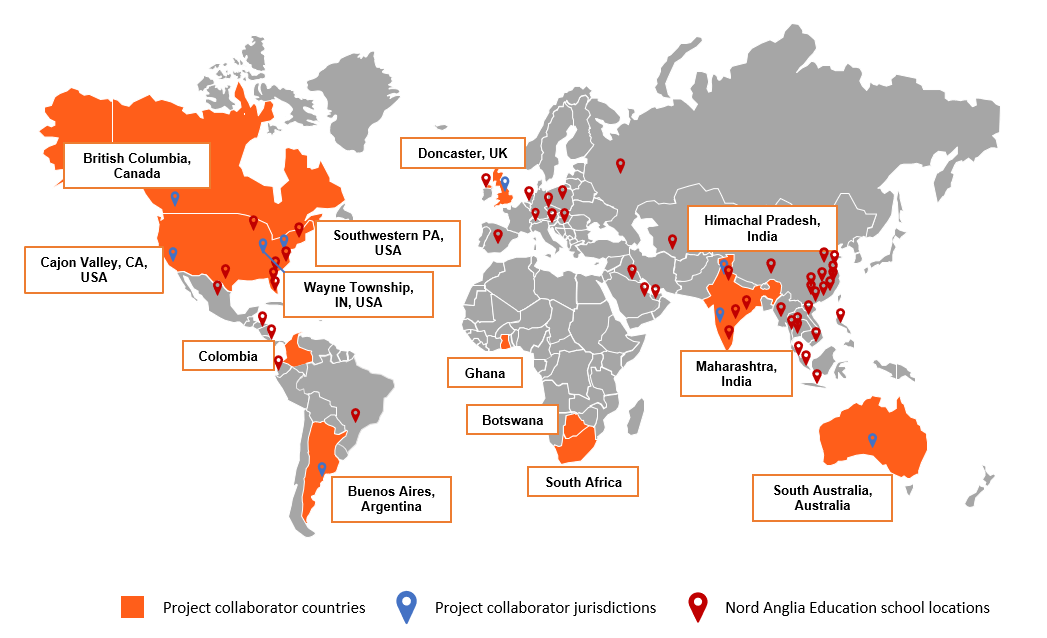

It is in this spirit that we at the Center for Universal Education (CUE) launched our Family Engagement in Education Network (Figure 1), whose members have been key collaborators on this survey.

Figure 1. CUE’s Family Engagement in Education Network

Effective parent engagement strategies that transform parent involvement into parent-educator partnerships have a significant positive effect on children’s academic and socio-emotional development.

Know your parents: Listening to parents’ beliefs, motivations, and perceptions

Education leaders and teachers across the globe have been finding new ways of communicating with parents and eliciting their perspectives amid school closures. In the process, many parents have shared their views on what is feasible for their family during remote learning, what type of technology they can access, their preferred method of communication, and their main concerns related to the pandemic and their children’s well-being. This is all crucial information to guide education decisionmakers on the many choices they face and help children continue to learn either at home, in newly reopened schools, or a combination of the two. But it remains to be seen if this level of communication will be sustained, and perhaps even more importantly, if it will help develop a strong, trusting relationship between families and schools.

As part of our research on parent engagement prior to the survey, we interviewed 50 education decisionmakers—from school leaders to ministers of education—in more than 15 countries. All decisionmakers were focused on addressing education inequality and on helping students develop strong academic competencies alongside lifelong learning skills such as agency, teamwork, empathy, and digital literacy. All expressed concern over how to better develop a dialogue and shared understanding with parents and families around their children’s learning and development. Most have had little formal training (either through teacher or administrator development courses or other opportunities) on the topic of parent and family engagement. Indeed, parent and family engagement appears to be given short shrift in many education professional development courses around the world.

The first—and perhaps most important step—to developing deeper relationship with parents and families is to listen to their beliefs, motivations, perceptions, and aspirations with respect to their children and education. We are sharing the initial results from our global survey of parents as a contribution to this first step.

The first—and perhaps most important step—to developing deeper relationship with parents and families is to listen to their beliefs, motivations, perceptions, and aspirations with respect to their children and education.

About the survey

Between May 2020 and January 2021, we worked closely with our project collaborators to survey nearly 25,000 primary caregivers (i.e., the adult who assumes the most responsibility in caring for the health and well-being of the child) across jurisdictions in the aforementioned 10 countries. Survey instruments were piloted and survey items were modified by jurisdiction for cultural and contextual relevance. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, a mix of online and live-call survey techniques were used. All survey items were optional such that respondents could choose to provide a response to a question without responding to the previous or subsequent questions. As a result, the response proportions per survey item options do not always sum to 100 percent (i.e., for some survey items, the response total is less than 100 percent for questions skipped by some respondents, and for other survey items, the response total is greater than 100 percent for questions where respondents could report multiple responses). Table 1 provides a summary of the survey methods.

Table 1. Methods for the global survey of parents’ and primary caregivers’ experiences, beliefs, and perceptions of their oldest child’s education

| Qualified respondents: | Parents or primary caregivers of children in formal schooling, preschool through end of secondary |

| Total number of respondents: | 24,759 |

| Primary school respondents: | 42%* |

| Junior secondary school respondents: | 25% |

| Senior secondary school respondents: | 33% |

| Confidence level: | 95%: Sample sizes were determined in advance to be representative within a 5% margin of error of the jurisdictions where survey was administered (e.g., district, state, or national level) |

| Languages offered: | Afrikaans, Arabic, English, Farsi, French, Haitian Creole, Hindi, Mandarin, Marathi, Setswana, Spanish, Swahili, Twi, Vietnamese, and Xhosa |

For coordination and data analysis purposes, project collaborators are grouped into 14 jurisdiction clusters. They include: Botswana; British Columbia, Canada; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Cajon Valley, California, USA; Colombia; Doncaster, U.K.; Ghana; Himachal Pradesh, India; Maharashtra, India; Nord Anglia Education; South Africa; southwestern Pennsylvania, USA; South Australia, Australia; and Wayne Township, Indiana, USA (see Figure 1).

To learn more about individual jurisdictions and their survey findings, download the technical reports.

Survey results

Parents desire a ‘new’ kind of education for their children

There are multiple insights from the survey results, but we have focused here on five specific insights including parents’ beliefs about the most important purpose of school, parents’ pedagogical preferences, parents’ indicators of quality education, parents’ alignment with teacher beliefs, and how parents’ beliefs are formed. Across these insights, we find three themes broadly reflected in parents’ voices:

- Parents are demanding a “new” type of education. Most parents desire a “new” type of education for their child—one that looks to socio-emotional development alongside academics and that uses innovative teaching and learning approaches that are interactive and social in nature versus direct instruction with little interaction.

- Teachers are important influencers of parents’ beliefs. Teachers play a central role in shaping parents’ beliefs about what makes a quality education, and parents desire to have a shared vision of this quality education with their children’s teachers.

- Decisionmakers must get to know their students’ parents. Education decisionmakers must get to know the parents in their jurisdiction: While there are similarities across regions, each jurisdiction has meaningful distinctions that require a nuanced understanding in order to build trusting family-school relationships.

Below we describe the survey results for each of the five insights.

Insight 1: Parents’ beliefs on the most important purpose of school

Schools play multiple roles in supporting children’s learning and development. These can include preparing students for the world of work and for post-secondary education. They can also include helping students develop socio-emotional competencies to help them flourish individually and be constructive members of society. Understanding parents’ beliefs about their views on the most important purpose of school is an important first step to understanding parents’ perspectives on their children’s education.

While parents surely value the multiple roles school play, we sought to understand their primary aspiration for their children through education. Based on the literature, as well as feedback from our project collaborators, we provided parents a menu of five options on the purpose of schools. Specifically, we asked parents to respond to the statement “I believe that the most important purpose of school is” by choosing from the below options:

- Academic: to prepare students for post-secondary education (i.e., college or university) through rigorous content knowledge across all academic subjects.

- Economic: to prepare students with the skills and competencies needed for the workforce.

- Civic: to prepare students to be good citizens who are prepared to lead their political and civic lives.

- Socio-emotional: to help students gain self-knowledge, find their personal sense of purpose, and better understand their values.

- Other

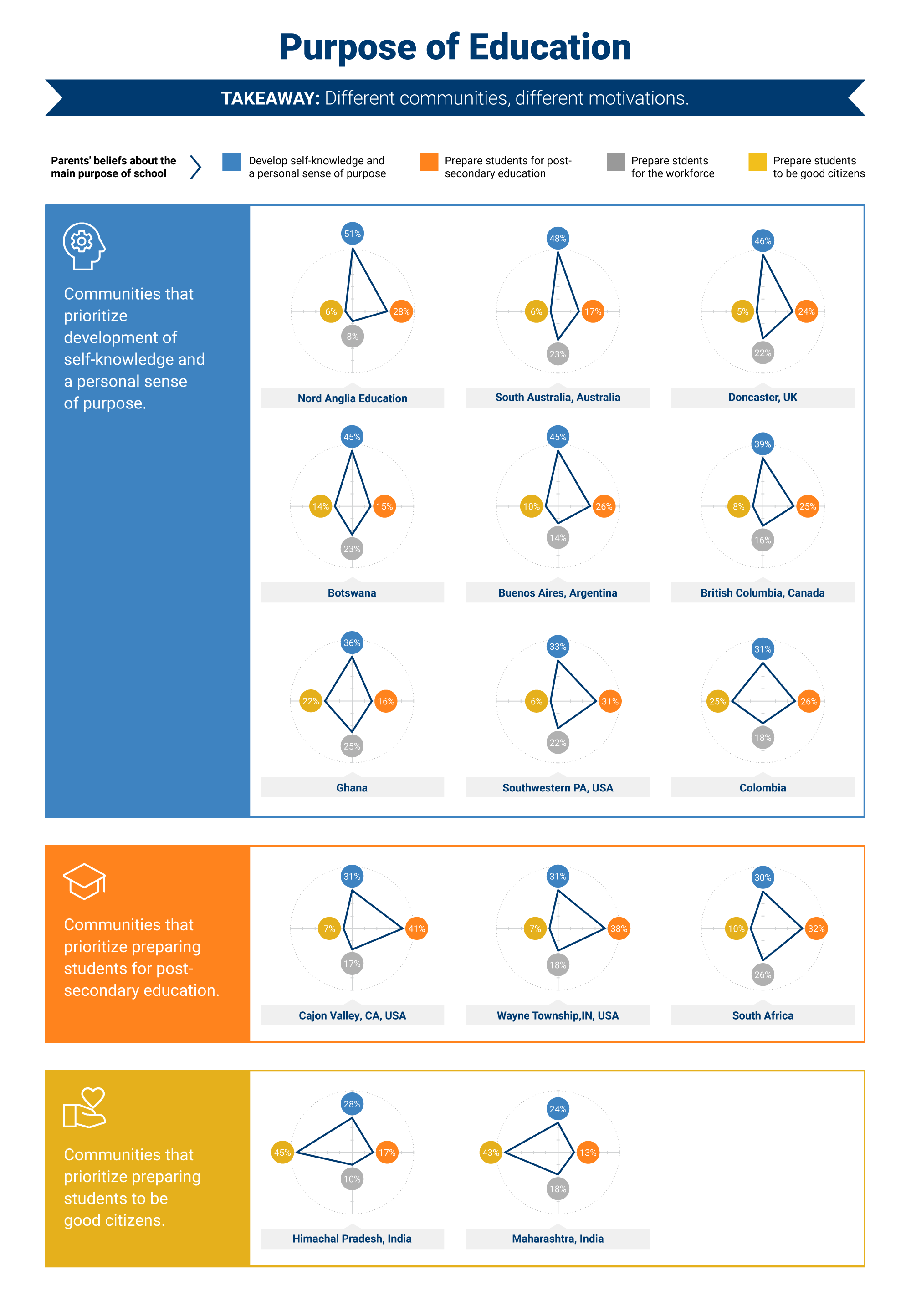

The findings reveal several themes. First, each jurisdiction shows a different pattern with regard to what their parents believe about education (see Figure 2). This means that there is wide variation in parents’ beliefs about the most important purpose of school across jurisdictions and that it is unwise for education decisionmakers to assume they know parents’ hopes for their children. For example, it appears some common refrains such as “Working class parents care most about helping their children get jobs” or “Working class parents care most about social mobility and helping their children go to college” may not always hold true. Indeed, as we discuss next, few parents surveyed believe the most important purpose of school is economic or civic.

Figure 2

Second, despite the variation from one jurisdiction to another, there emerged strong trends in preferences across jurisdictions. For example, in 9 of the 14 jurisdictions, children’s socio-emotional development was the most frequently identified purpose of school. These responses come from jurisdictions in North America, Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Australia. In three jurisdictions—two districts in the U.S. and one in South Africa—academic preparation was seen as the most important purpose of school. Although some parents across jurisdictions did identify the economic purpose of school as most important, it was the minority and in no jurisdiction was it the most frequently selected option. In just two jurisdictions—both in India—preparing young people to be good citizens was the most frequently identified purpose.

Third, the most important purpose of school shifts as parents’ children get older. Across all jurisdictions, parents of younger children preferred that schools focus on socio-emotional development, whereas parents of older children preferred a focus on academic development.

Insight 2: Parents’ pedagogical preferences

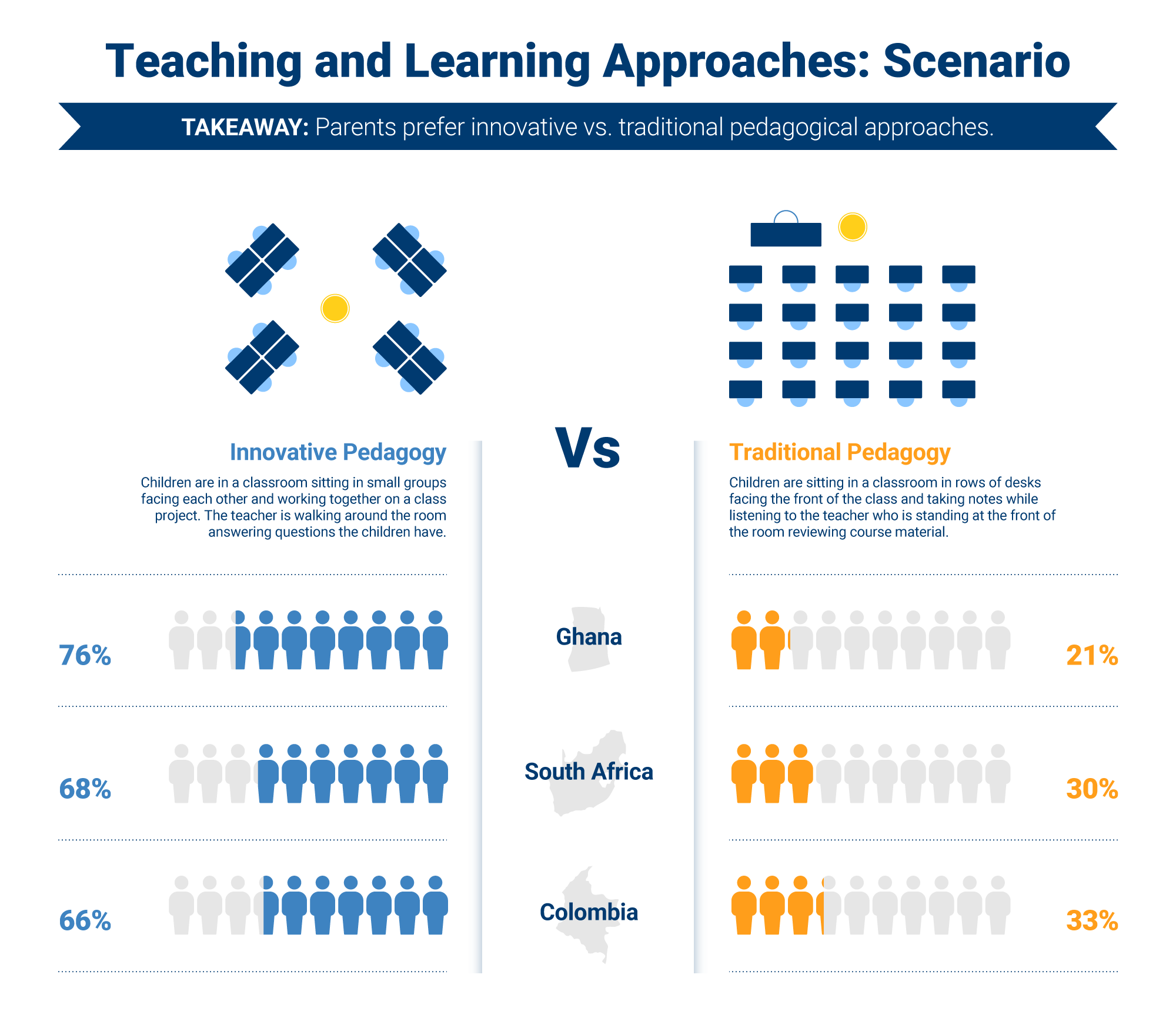

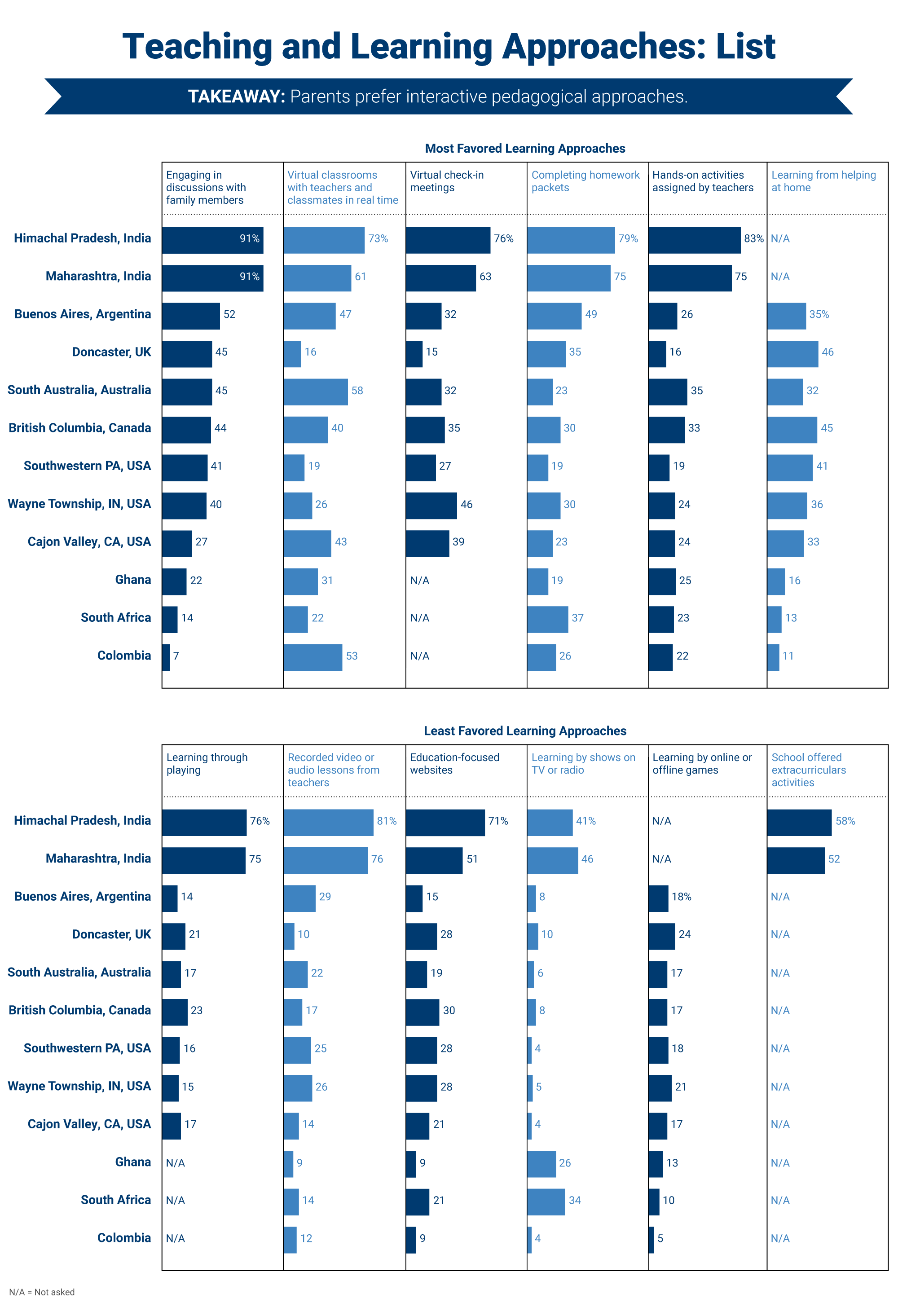

Parents’ interest in schools’ ability to help their children develop socio-emotionally is also reflected in the strong preference across jurisdictions for innovative pedagogical approaches that emphasize the social nature of learning. We sought to understand parents’ perspectives on teaching and learning strategies by asking them to rank or choose between examples of “traditional” pedagogical approaches and “innovative” pedagogical approaches. We defined “traditional” pedagogy as teaching and learning strategies that are widely used around the world and emphasize knowledge acquisition through educator-led instruction with limited student interaction. We defined “innovative” pedagogical approaches—drawing on OECD’s definition—as those that use a range of teaching and learning strategies, including interactive approaches (e.g., group-based work facilitated by educators, playing games, or discussions with family members.)

We used two approaches to solicit parents’ perspective: We gave parents a scenario1 or asked them to rank their preferences between a list of pedagogical approaches. In Colombia, Ghana, and South Africa, parents responded to a vignette that solicited their preferences between a school using “traditional pedagogy” and a school using “innovative pedagogy” (see Figure 3). Specifically, the question read:

“You are helping a friend choose a school for her 10-year-old child. She can send her child to one of two schools and you go with her to visit both schools. In one school you see: a) children are sitting in a classroom in rows of desks facing the front of the class and taking notes while listening to the teacher who is standing at the front of the room reviewing course material; and b) children are in a classroom sitting in small groups facing each other and working together on a class project. The teacher is walking around the room answering children’s questions. Which school would you suggest that your friend chooses to send her child to?”

Parents could also respond that they did not know which option they preferred. Across all three countries, the majority of parents indicated that they preferred the school using innovative pedagogy over the school using traditional pedagogy. There are variations by district within each country, and in South Africa and Colombia in particular, approximately 1 in 3 parents prefer the traditional pedagogical approach versus 1 in 5 in Ghana. Nevertheless, across these three countries there is a strong preference for interactive pedagogical approaches.

Endnotes

- 1. We used vignettes to elicit parents’ opinions about education specifically for two of our survey items in Colombia, Ghana, and South Africa as a way to examine and avoid the effects of experimental demand (a situation where survey respondents form an interpretation of what the survey designers expect as “good responses,” and thus respondents may subconsciously change their behavior to fit that interpretation) on parents’ responses to our survey questions.

Figure 3

In the remaining jurisdictions, we asked parents to rank the preferred ways their children were learning during school closures. Parents were able to rank their preferences or respond “not applicable” to a range of options— from strategies that provided little room for interaction such as “educator provided homework packets and recorded lessons” to interactive experiences such as talking with teachers online, discussing with family members, and helping around the home. There were differences across the jurisdictions, but several themes emerged (see Figure 4). First, parents across most jurisdictions preferred interactive and social approaches to teaching and learning, such as when their children engage in discussions with their parents, siblings, and/or other family members, as well as learning through hands-on activities assigned by their teachers. However, this was not the case everywhere—in South Africa, parents’ most preferred pedagogy is to have their children learn by completing homework packets. Across all jurisdictions except for Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Ghana, and South Africa, parents’ least preferred approach to pedagogy was learning through shows on TV or radio. It is important to note that while some parental beliefs about pedagogy trended in the same direction across the jurisdictions, we found differences in parents’ desires for how their children are taught, likely because of cultural traditions and practical considerations like access to the internet and television.

Figure 4

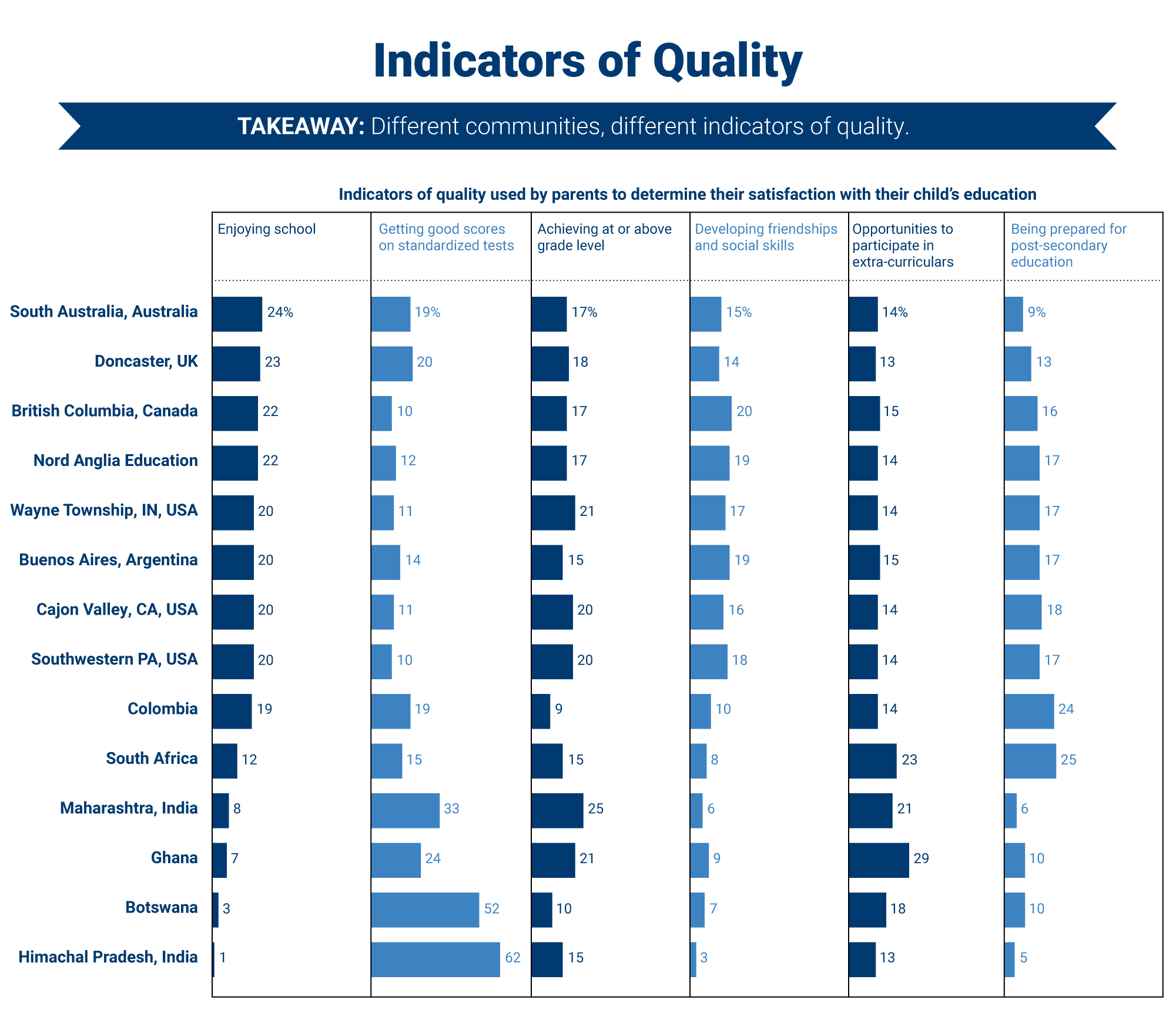

Insight 3: Parents’ indicators of quality education

Every parent makes an assessment as to the quality of his or her child’s education. Parents may do this instinctively as they go about their day and rely on a mix of informal or formal information, such as a comment by their child, an interaction with their child’s teacher, a neighbor’s child who graduates from school and goes onto college, a report card or exam results, or the school’s rankings and evaluations. The mix of information parents use to determine the quality of their child’s school serves as parental indicators of education quality. Parents’ ability to assess their child’s school is limited by the indicators or feedback loops to which they have access. Ultimately, schools or education systems more broadly determine what indicators or feedback loops to give parents, and parents must decide which of these—along with other informal indicators they access in their daily lives—they pay attention to.

In order to better understand how parents shape their beliefs about education, we asked parents about the feedback loops that they have access to and that they rely on as indicators of quality. Specifically, parents completed the statement “I am satisfied with my child’s education when my child is” by ranking six options:

- Exams: getting good scores on state/national standardized tests.

- Grades: achieving at or above grade level.

- Post-secondary preparation: being prepared for post-secondary education (i.e., college or university).

- Social: developing friendships and social skills.

- Extracurricular: being given opportunities to participate in extracurricular activities aligned to students’ interests.

- Happiness: enjoying school.

Several insights emerged from the responses (see Figure 5). First, except for parents in Africa and India, parents reflected the overall interest in children’s socio-emotional development and interactive pedagogical approaches by privileging indicators of quality related to their child’s happiness and social development. Parents also relied—but to a lesser extent—on children’s grades and participation in extracurricular activities as essential indicators of quality.

Second, there were stark differences with parents in Botswana, Ghana, South Africa, and India who relied on a very different set of information. Respondents from Botswana and India were almost solely focused on exam results as the indicator to judge if their child is attending a good school. This could be because exam results are the primary formal feedback loop schools and school systems provide parents. It could be that parents do not have access to other feedback loops, such as participation in extracurricular activities. But parents do have access to their children and could have chosen to include children’s social development and happiness as an indicator of quality. This may be related to parents’ perceptions of what schools are responsible for or conceptions of childhood. However, in several cases it may simply be that there are insufficient feedback loops to parents. In several instances, the misalignment between what parents’ state is the primary purpose of school and the indicators of quality they use is striking. For example, in Botswana and India, parents articulated a strong belief that the purpose of school was, respectively, socio-emotional and civic development. Yet, the indicators of quality parents most pay attention to are exam results.

Parents from Ghana also reported that they rely primarily on their children’s performance on standardized exams, while parents from South Africa indicated that they are most satisfied when their children are being prepared for postsecondary education. However, in both countries, parents indicated that they are just as concerned with whether their children are being provided with opportunities to engage in extracurricular activities.

Figure 5

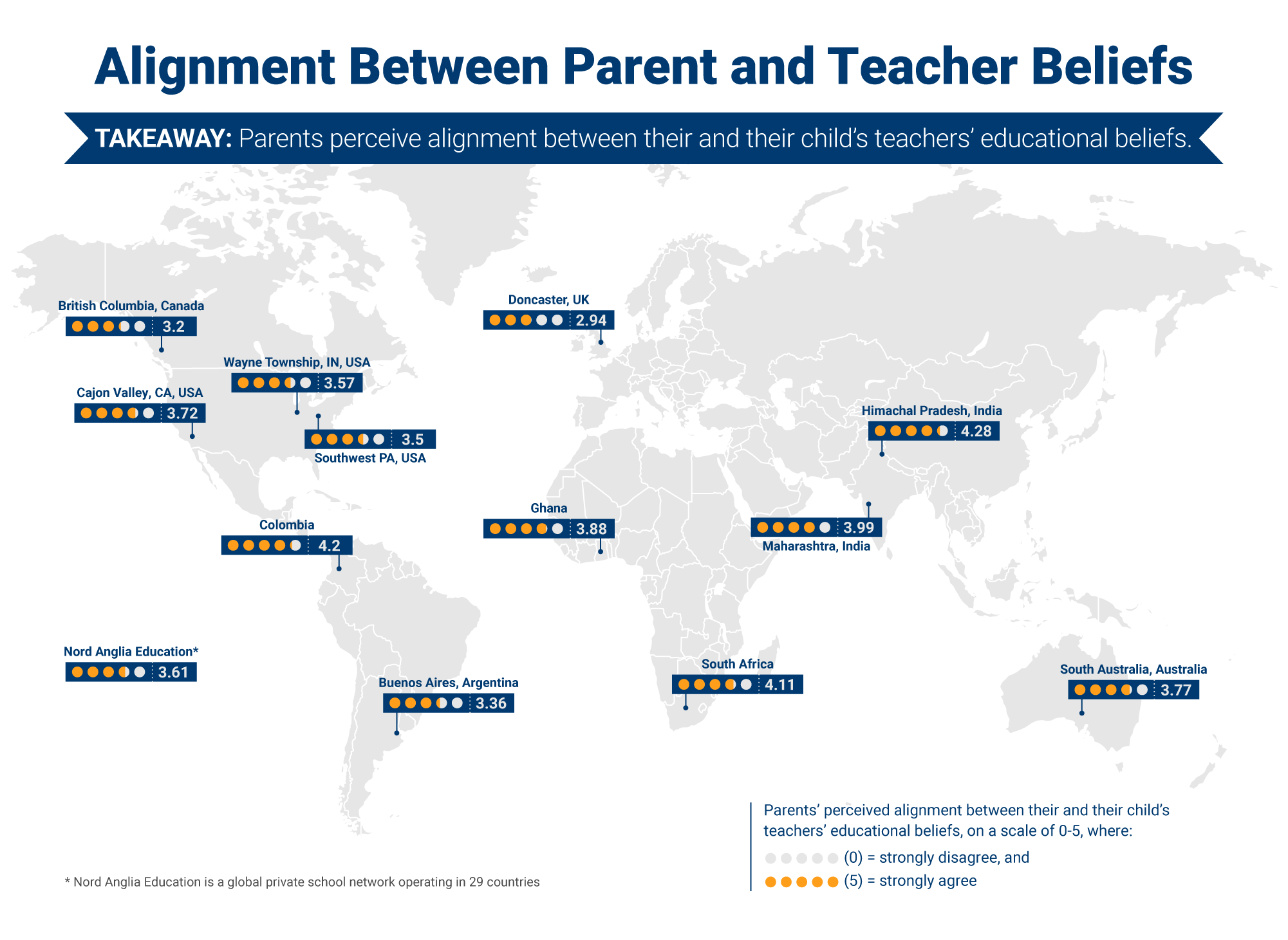

Insight 4: Parents’ alignment with teachers’ beliefs

We were interested in whether parents felt their beliefs were aligned with their children’s teachers’ beliefs. Did they perceive a shared vision of education with the school? Hence, in the survey parents were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the statement “My child’s teachers share my beliefs about what makes a good education” using a Likert scale from 0 for “strongly disagree” to 5 for “strongly agree.” Across all jurisdictions, findings showed that the vast majority of parents agreed that their children’s teachers share their beliefs about education, as evidenced by scores above 3 (see Figure 6). Interestingly, for the data we have collected so far from teachers, the feeling seems to be mutual. Together with our project collaborators, CUE is currently collecting data from teachers in the same jurisdiction where parents were surveyed. To date, data has been collected from Ghana, Wayne Township, Maharashtra, Nord Anglia Education, and southwestern Pennsylvania. Teachers responded to the statement “My students’ parents share my beliefs about what makes for a good quality education” and showed a high level of perceived alignment.

Figure 6

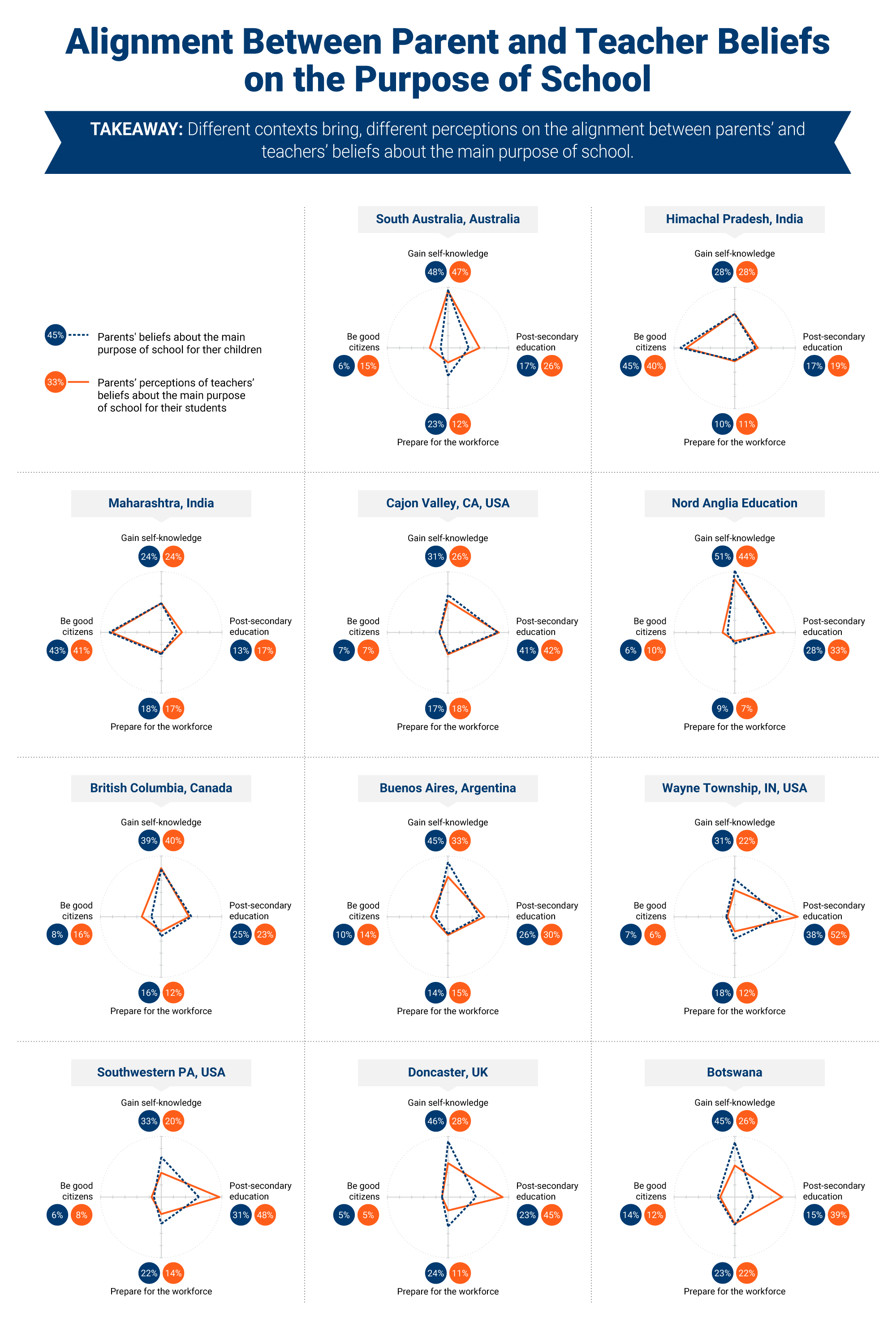

However, when parents are asked more detailed questions about how their beliefs align with their child’s teachers, a mixed picture emerges. Parents were asked to report their perceptions of what teachers believe is the most important purpose of school using the same four options discussed above in Insight 1. In over half the jurisdictions where this question was asked, parents reported that they believed teachers held different beliefs around the most important purpose of school. Some of the differences were minor, but many illuminated stark perceived differences (see Figure 7). For example, in Botswana, Doncaster, and southwestern Pennsylvania, parents expressed deep misalignment between their beliefs and their perceptions of teachers’ beliefs. In all cases, parents perceived teachers to be more focused on the academic purpose of school than parents themselves.

Figure 7

The contradiction between these findings in various jurisdictions may indicate that parents have a strong desire for a shared vision with their child’s educator even when they believe they do not. This may be because, as we will see next, parents rely so heavily on teachers to inform their perspectives about the quality of their child’s education.

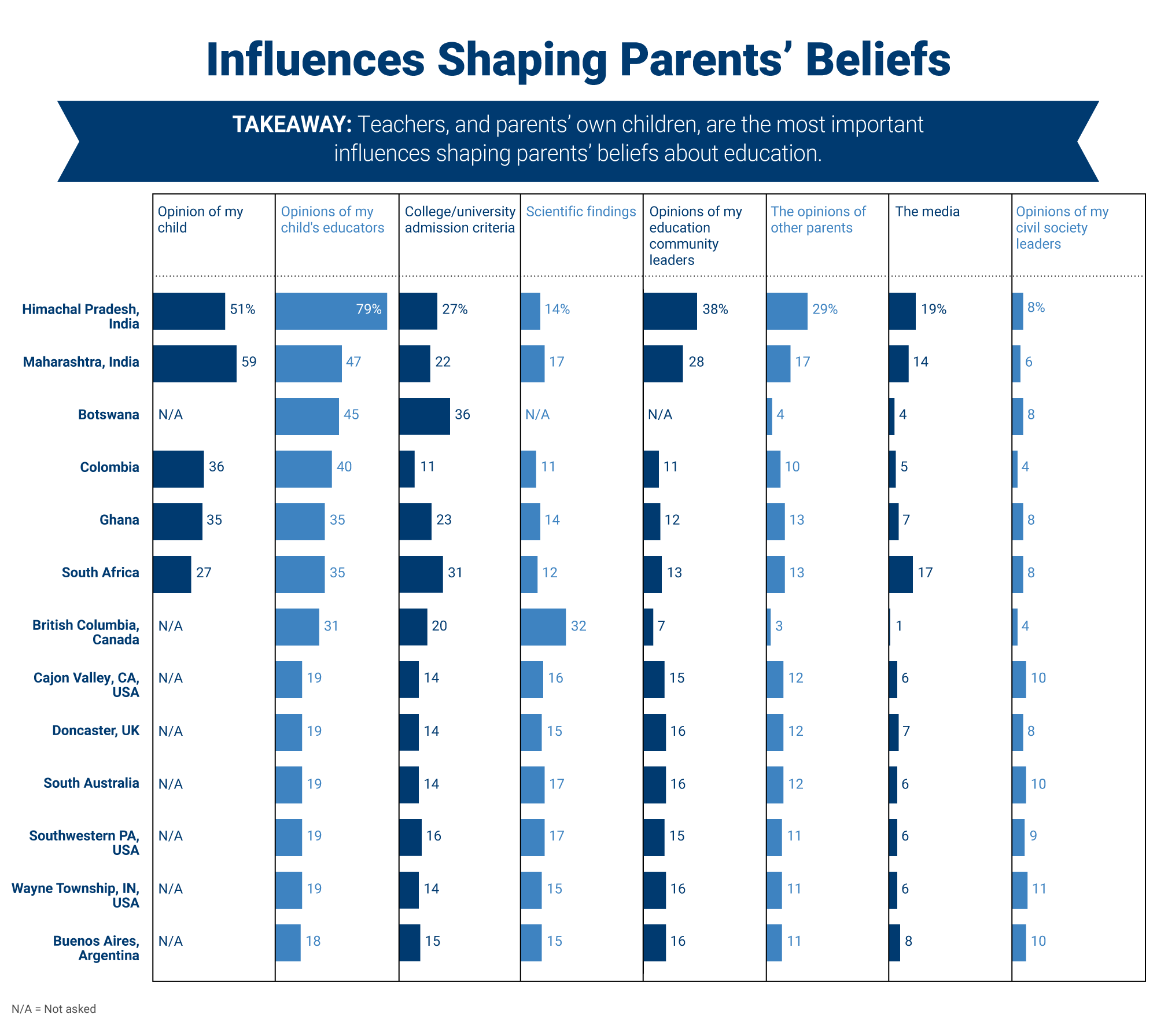

Insight 5: How parents’ beliefs are formed

What influences parents’ beliefs about what makes a good quality education for their child? How are their perspectives shaped and informed? Who do they listen to? To understand not what parents’ beliefs are but rather what influences their perspectives, we asked parents “What influences your perspective about what makes for a good quality education for your child?” and had them rank nine options:

- Influence of personal relationships:

– The opinions of other parents

– The opinion of my child - Influence of educators and the education system:

– The opinions of my child’s educators (e.g., teachers and paraprofessional educators)

– The criteria required for admission into college/university

– The opinions of my education community leaders (e.g., school administrators, district directors, and policymakers) - Influence of non-school related entities:

– The media

– Scientific findings from fields such as psychology, the learning sciences, sociology, etc.

– The opinions of my elected officials

– The opinions of my civil society leaders (e.g., faith-based community leaders, nongovernmental organizations, grass-roots community groups)

The fact that parents rely so heavily on their children’s educators, as well as their children, for guidance on what makes a good quality education suggests that there is strong potential for partnership and collaboration (see Figure 8). Educators hold a unique and privileged place in the influencing of parent perspectives, and parents—as discussed above—are eager for alignment on vision and approaches. Across all jurisdictions, we found that parents do not rely on each other as important sources of information about the quality of their children’s education. This suggests that parents may be devaluing their important position as agents of change in the education system.

Figure 8

Conclusion

These findings highlight the importance of better understanding parents’ beliefs, desires, and motivations for their children’s education. First, most parents want a “new” type of education for their child that prioritizes socio-emotional development alongside academics and that uses innovative, interactive, and social approaches to teaching and learning. Second, teachers play a central role in shaping parents’ beliefs about what makes a quality education, and parents want a shared vision of what constitutes this quality education with their children’s teachers. Third, education decisionmakers must get to know the parents in their jurisdiction to understand meaningful distinctions about parents’ beliefs and desires.

We also learned that it is equally important to engage with teachers to gain insight into their beliefs, desires, and motivations for how best to serve their students. Identifying areas of alignment and misalignment between parents’ and teachers’ perspectives on schooling can help contribute to an informed dialogue that builds trusting relationships. We look forward to sharing completed results of CUE’s global teacher surveys in forthcoming publications and presenting strategies for parent and family engagement, especially in contexts of navigating education change, in our upcoming playbook, which will be available in fall 2021.

Technical reports

For a description of each of the 14 jurisdictions’ education systems and detailed survey findings, download the technical reports.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our colleagues who have helped us in the process of developing and conducting our global survey.

We are especially grateful to the project collaborators in our Family Engagement in Education Network without whom this survey would not have been possible; our CUE team members, Lauren Ziegler, Sophie Partington, Rachel Clayton, Jessica Alongi, Grace Harrington; and academic colleagues for their advice and guidance, Drs. Karen Mapp, Sharon Wolf, William Jeynes, Joyce Epstein, and Sonya Krutikova.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Brookings gratefully acknowledges the support provided by the BHP Foundation and the LEGO Foundation.

Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.