Lea County,

Safeguarding Rural Economic Prosperity Through Transformative Leadership

The refrain of rural America falling behind is problematically passive.

The refrain absolves the troupe of policymakers of accountability for an inchoate federal rural policy framework, which dictates how billions in omnibus federal spending are distributed throughout rural communities annually. The discourse framing this narrative obscures a political process dominated by a corporate agriculture lobby which, in coordination with Congress, sets the national rural policy agenda that has sequestered the bulk of Farm Bill benefits for large farm-based conglomerates for decades.

This political partnership ignores the tremendous heterogeneity coloring rural economies and effectively dooms the non-agricultural residual to fall behind by design. What’s worse, the very phrasing “falling behind” fails to acknowledge the power and agency hidden within

rural communities that have transformed community-owned assets into drivers of societal well-being and critical community-enhancing institutions.

74,455

total population

12.6%

poverty rate

$66,780

median income

4,202

small businesses

[We] started saving a long time ago, knowing that whenever there’s a boom, you better save every penny you can because there will be a bust…, but you can’t just sit on the money—you’ve got to invest it. Because your rainy day will dwarf your rainy-day fund if you haven’t made the right investments at the right time. It’s making smart investments. I like that. That’s a great culture to live in.

– Jennifer Grassham Executive Director, Economic Development Corporation of Lea County

The unresolved dualism between the federal energy agenda and the national rural policy setting creates a fundamental gap with profound implications for the economic well-being of oil and gas rural communities. Without adequate support, these economies are highly susceptible to market shocks that jeopardize growth potentials and weaken communities’ capacity to restore balance.5 Embedded in the rural economic multiplex is a proliferation of oil-producing counties powering the U.S. energy basket, many of which are predominantly Hispanic and deeply engaged in building resilient economies that can respond to the challenges of an ever-changing global economy. Notably, a few of these extractive economies have defied deficit trends of declining job growth and depopulation, typifying the vicious boom–bust cycles characteristic of oil and gas–addicted economies. Lea County, New Mexico has managed to deftly navigate the interplay between oil depressions and transformative rural placemaking policy to establish an EnergyPlex brand anchored in local community well-being.

TURNING SCARS INTO GENERATIONAL COMMITMENTS

Capricious oil market forces regulated Lea County’s fortunes until the mid-1980s.

Like other boomtowns, climbing oil prices brought new jobs, fresh faces, and rising revenues. Later, when tides turned, the county and other oil towns saw their communities empty out as itinerant workers moved in search of gainful employment. The ebb and flow of these cycles usually reversed boom-time gains in jobs, housing, and household incomes. Jennifer Grassham, Executive Director of the Economic Development Corporation of Lea County, shared that the 1985 bust cycle was particularly devastating. She recalled a common feeling of defeat: “When it rains here, it pours. The 1980s broke us. [It was] a really hard bust and we [said], ‘Never again.’ … I have those scars. We’re not doing that again.”

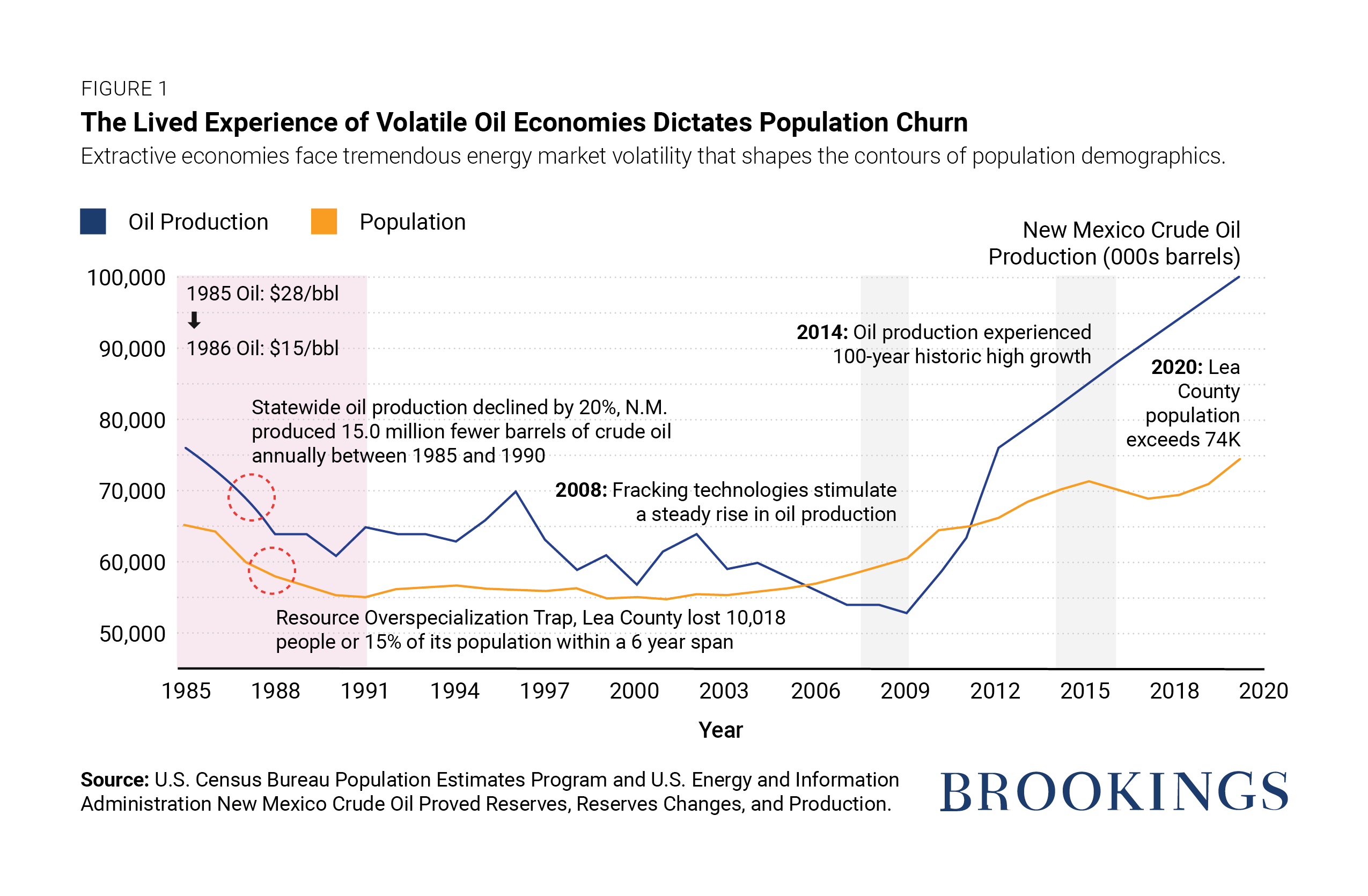

Director Grassham was referring to a period of extreme volatility when oil prices plummeted 46% in a single year—from $28/bbl in 1985 to $15/ bbl in 1986.6 Oil production cratered, forcing multinational companies to restructure or adopt austere cost-savings measures that wiped out thousands of jobs in the county. This ruinous shock prompted an exodus of residents: the county’s population shrank by roughly 10,000 people between 1985 and 1991 (see Figure 1).

The oil shock-induced migration represented an astounding 15% of Lea’s population. This figure corresponds to acute community desolation, with 1 in every 6 residents leaving their homes behind. In the absence of automatic stabilizers or federal support to mitigate the scale of economic losses, Lea County’s leadership harnessed the scars of their wounded experience and the county’s residual assets to invest in protecting the future well-being of the community. The county emerged from the 1980s crisis with a deep-rooted savings mindset and a commitment to enacting smart policies to weather inevitable downturns. Director Grassham noted, “[We] started saving a long time ago, like, knowing that whenever there’s a boom, you better save every penny you can because there will be a bust…, but you can’t just sit on the money—you’ve got to invest it. Because your rainy day will dwarf your rainy-day fund if you haven’t made the right investments at the right time. It’s making smart investments. I like that, that’s a really great culture to live in.”

Lea County adopted a conservative fiscal ethos, which translated into policy through successive governing administrations. This philosophy is now an integral part of the county’s culturally informed policy toolkit—one that has seen the county withstand severe downturns such as the Great Recession without losing large swaths of the population or experiencing income volatility like some of its rural counterparts.

SMART INVESTMENTS FOSTER GROWING COMMUNITIES

Destabilizing shocks provide a broad canvas to assess resiliency-reinforcing strategies and probe changing fundamentals.

Lea County’s long-running recovery was grounded in a context of a robust nationwide oil production rebound and a coincident shift in drilling technologies. The latter trend could explain the attenuated relationship between oil barrel production and population growth between 2008 and 2020; see Figure 1. The slopes of the two series were closely aligned in the 1980s. However, the advent of hydraulic drilling technology and general-purpose automation technologies partly altered economic foundations such as job growth. Numerous researchers have documented the uncoupling of job creation and economic growth caused by technological advances.8 Although technology-driven changes stunts job creation, these shifts open fertile pathways that enable non-traditional groups to participate in the energy economy.

New drilling technologies have made oil production and oil service occupations less labor-intensive while markedly improving the physical safety elements of these jobs. In some ways, drilling technologies have had an equity-enhancing effect on Lea County’s energy sector by creating avenues for women like Rosa Carrillo to participate in the high-wage sector. Ms. Carrillo started Got Safety, an oil and gas safety company, in 2007 to provide income but retain the flexibility to help care for her young family: “I wanted to take a leap of faith and go on my own.” Got Safety currently employs a blended workforce of 15 men and women, though women predominate Ms. Carrillo’s staffing matrix that provides field safety training to 30–40 companies monthly. Lea County is home to many young, small firms like Ms. Carrillo’s. She proudly averred that “[The city of] Hobbs is a hub for entrepreneurs…because there are so many companies in this area, that’s why my business does so well. They utilize us when they first open to get them structured and [to develop] a safety program. From there, they’ll hire within the company permanently.” Lea County’s oil service economy has evolved to include entry points for the roughly 34,000 women living and growing their families in the county.

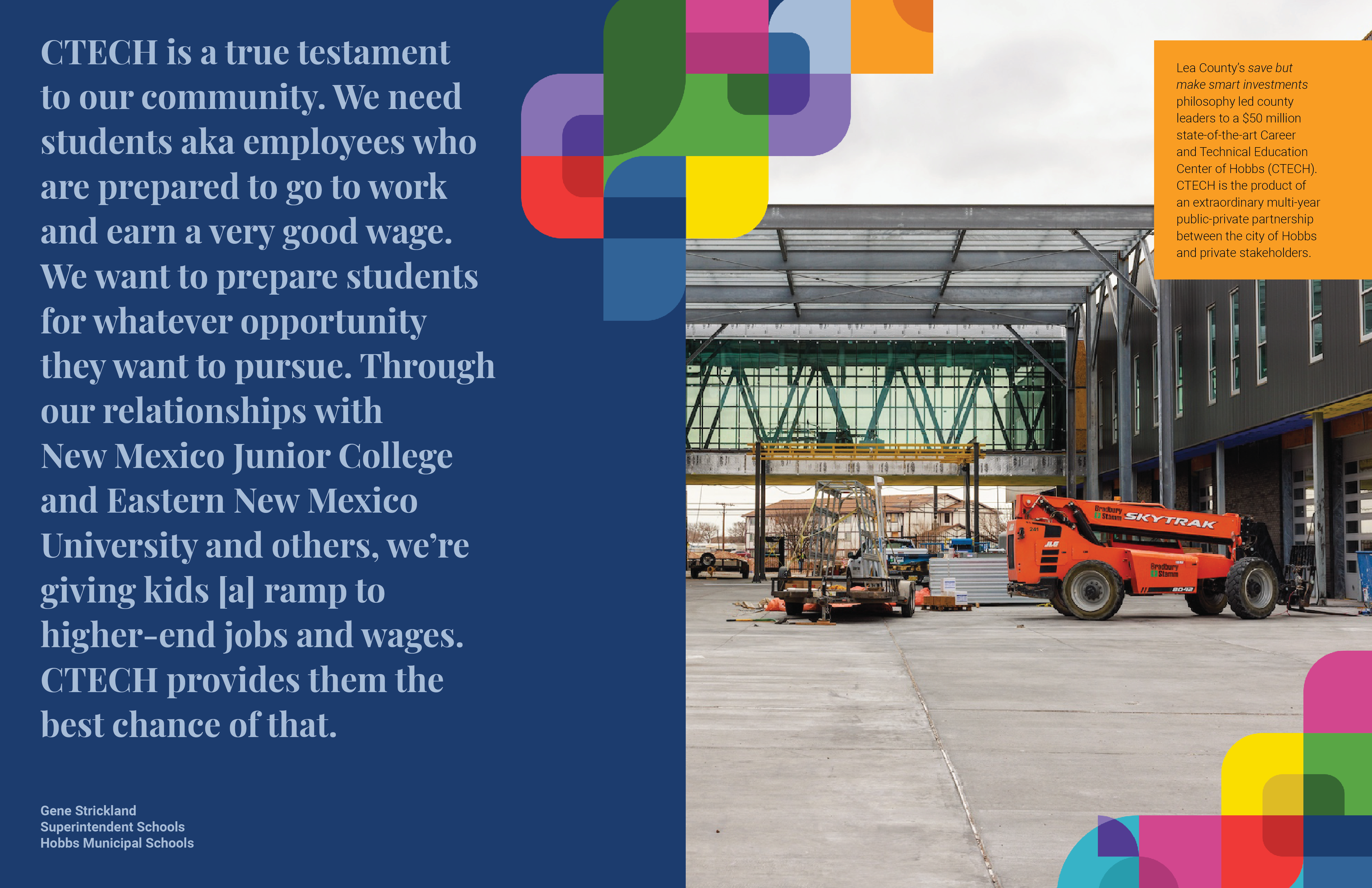

Building an elastic workforce is vital to Ms. Carrillo’s growth and to attracting high-value firms, such as URENCO USA and other uranium enrichment companies, to Lea County. In keeping with the save but make smart investments ideology, this spring, county leaders will open the $50.0 million state-of-the-art Career and Technical Education Center of Hobbs (CTECH)—a walkable, open-border educational campus. CTECH is the product of an extraordinary multi-year public-private partnership between the city of Hobbs and a cluster of private stakeholders, including the Permian Strategic Partnership—a contingent of 20 of the largest oil companies based in the Permian Basin that provided a $12 million capital injection. It is worth noting that a mix of oil and non-oil strategic partners participated in this effort; corporate sponsors from the auto manufacturing and hospitality sectors are similarly vested in this inspiring project. CTECH was explicitly designed as a community co-designed initiative to respond to the regional skills gap in high-skilled, high-demand jobs and to cultivate an adaptable workforce equipped with growth-oriented skill sets. Workforce preparedness for longer-range economic diversification lies at the heart of the vision for this educational campus. The county is building the pillars of a non-carbon energy value chain featuring hydrogen, nuclear, and carbon sequestration verticals. Many of Lea’s incumbent workers can transfer legacy skills to existing oil service horizontals. But they’re less prepared for a diverse zero-carbon economy, CTECH by design will fill some portion of this structural workforce gap.

CTECH’s community governance structure is remarkably innovative. Responsibility for the school’s longevity and success is shared between the school board and the coterie of private funders. Each private funder signed a formal social contract with the school board to create shared equities in CTECH’s performance-based outcomes while steering its governance. As Zeke Kaney, Director of Career Tech Education for the District of Hobbs, explained: “Structurally, we’ll have a steering committee and pathway advisory councils [that] will advise us as we move forward. Each has quarterly reporting requirements on performance goal certification completions, successful hires, or intern placements. Instead of focusing on graduation rates or credits, now we’re focusing on how this relationship works with the community. They’ll guide us. Kudos to our community and partners. This work was too important not to do.”

Lea’s community-centered ethic is imbued with the language of shared governance. A common understanding implicit in this contract structure is the accountability and promise to shoulder equal responsibility for outcomes and to co-construct healthy resolutions. Such structures ensure that the collaborative will prioritize the well-being of Hobbs’ opportunity youth; that is, curriculum design will serve long-term educational standards in ways that accord with workforce demand instead of functioning as an expansive subsidy for employers who abdicate the duty to invest in their niche training needs. While CTECH’s stakeholders are keenly aware of future challenges and the probability of mistakes, they are confident in their ability to come together as a community to solve problems rather than ascribe blame. Fortunately, with stakes this high, CTECH’s adherents are more concerned about democratizing accountability and opening communication channels through which contributors can find solutions.

SCAFFOLDING PLIABLE PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS

Oil economy populations are especially geographically mobile.

In Lea County, as in other rural energy-regulated economies, the magnetic population flow gravitates to barrel productivity and comprises two distinct worker demographics. The first contingent encompasses people moving to the county due to planned company relocations or expansions, either importing high incomes and higher levels of educational attainment or technical expertise. The second cohort corresponds to a less organized dynamic of transient workers; these people are generally unemployed and move to Lea County in search of job opportunities. These flows had uncanny parallels to the boom cycle in the past, but in the aftermath of the subprime crisis, many of these households became increasingly rooted in the area: Lea County’s population grew by 25.2% between 2008 and 2020 (see Figure 1). It is difficult to quantify the fractional shares of organized or unplanned movements, but what’s clear is that the county needed to bolster critical public institutions to meet the social service needs of its transplanted residents.

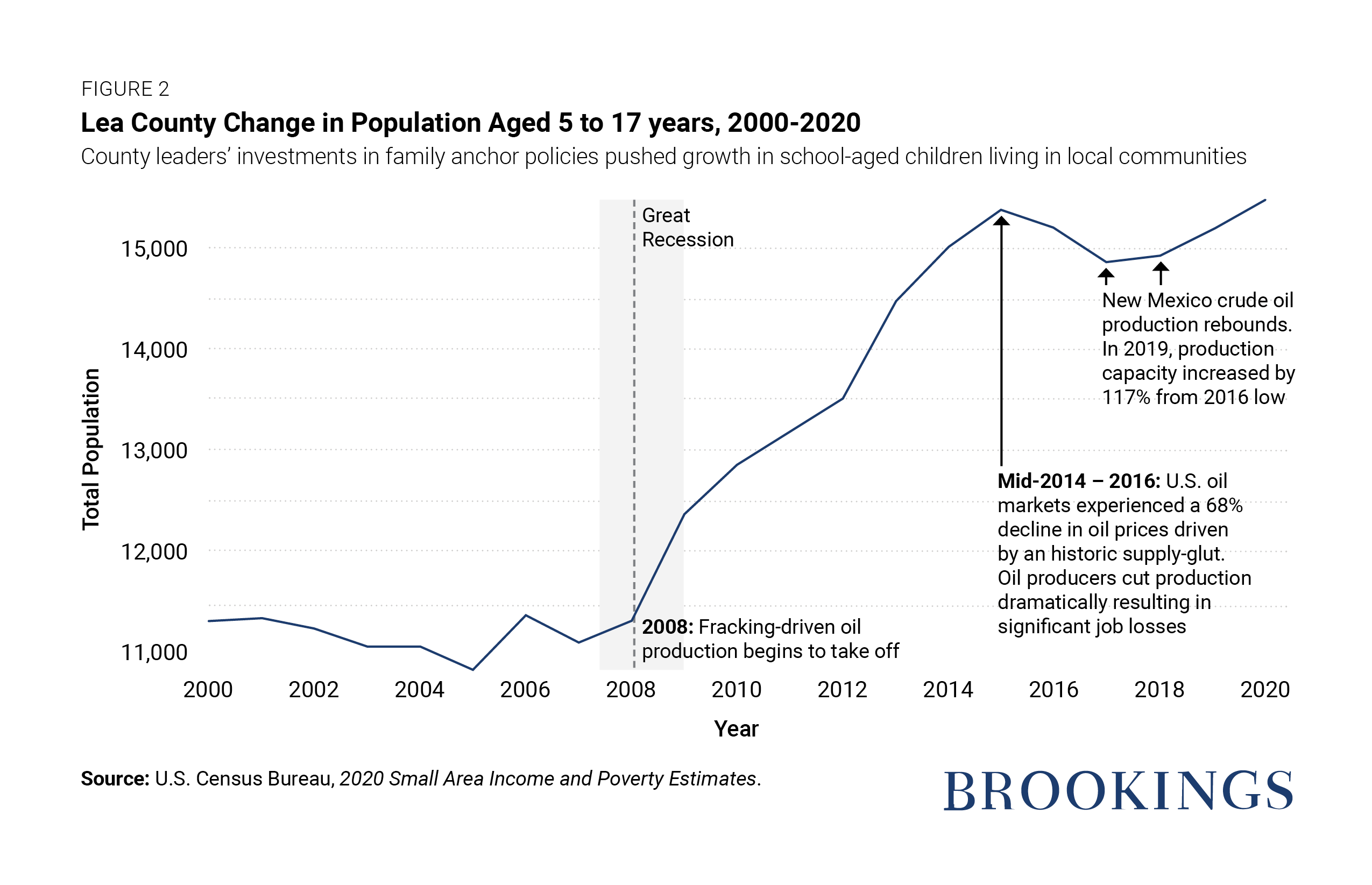

The population of school-age children aged 5–17 outpaced total population growth. In the wake of the financial crisis, Lea County’s juvenile populace increased by 37% (see Figure 2). The compositional dynamics of this growth structure have significant implications for public services such as healthcare, education, and housing.

Local policymakers attribute their population retention to the general economic malaise that had slowly permeated other industrial sectors. In general, oil prices fall too low in bust cycles to maintain employment or competitive wages, driving workers to explore options in alternative sectors such as manufacturing. Coincidentally, while the subprime crisis destabilized housing and housing-adjacent sectors during years of financial crisis, oil economies experienced similarly scaled disruptive forces. Oil prices cratered from a peak of $147/bbl in July 2008 to a critical low of $32/bbl in December 2008—80% of oil’s value evaporated within six months.9

Workers of all ilk were sandwiched between two crippling depressions that pushed the national unemployment rate to double digits by 2009, while Lea County’s unemployment rate rose to 7.4% in the same year.10 Bear in mind that these rates only capture workers actively looking for work, not the millions who have given up. At the community level, households endured the full spectrum of desolate job losers. The lone bright spot for Lea County was low population churn, according to Dir. Grassham’s reflections on the period: “The oil field busted at the same time the rest of the country did. There weren’t places for people to go. We were watching for the school system to have an exodus. And it didn’t. We’d never seen this happen before, which was nice because we kept that population, and then we kept building off of that.”

Rising population density creates vibrancy in rural communities. Transplants import vital skills, technical expertise, and novel ideas that accelerate the dissemination of new technologies crucial to increasing rural markets’ competitiveness. Strong levels of entrepreneurial dynamism fuel a generative agglomeration process that attracts high-growth firms with immense job creation potential.11 Despite its benefits, migration-driven population growth brings challenges that strain public service infrastructure. Naive attempts to absorb new residents without adequate policy support will create negative externalities and weaken critical social bonds indispensable for place-based cultural identities.12 Lea County wisely anticipated the need to scaffold pliable public institutions that could respond to high-frequency population churn and serve the increasing number of families willing to stay rooted in the county. In 2021, the county began construction on a $110.0 million community hospital. The new facility will bring critical women’s health and other high-quality healthcare services to the county as other rural counties see their critical care facilities close, putting enormous obstacles between primary care and sick patients.13

Lea County’s policy response to its growing community base has been deliberately broad and intentionally focused on family well-being. CTECH’s efforts to remove barriers, including transportation, by placing its remarkable facility within a socially vulnerable community ensures that transit costs would not hinder attendance. Moreover, mindful upfront decisions to subsidize certifications and not unfairly punish students for discipline or truancy records have gone a long way to ensuring that young people from disadvantaged backgrounds have fair access to mobilizing opportunities. Affordable housing is paramount in households’ decisions to remain in Lea County. The county’s sustained investment in affordable housing sets it apart from its peers, as local officials work with developers to impel the construction of single-family homes. The city of Hobbs, for example, grants private developers $5,000 and $10,000 in incentives to encourage new development projects.

Affordable housing in rural areas is as much about inventory as the supply mix. Given bifurcated migration flows, the county continually works to improve multifamily housing options that help right-size housing needs with available inventory, especially for single-person households. Increasing apartment rentals creates a closer match between available stock and families’ housing needs. Incidentally, better housing matches reduce cost pressures, especially when single-person households are not overconsuming housing. Affordable housing developers have brought a raft of multifamily rental projects online in recent years. Thanks to federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits, the projects are modern and beautifully designed. Lea County understands that placemaking is a homemaking process for families of different backgrounds. Some choose to build homes there, whereas others see the county as a temporary place to live and work. Regardless of permanence, policymakers are intent on braiding placemaking tools into a coherent strategy that entices residents to stay and shore up the county’s resilience.

The multifamily housing developments are really sharp looking, probably our nicest-looking stuff in town. To the credit of the developers, they didn’t take just the cheap way. They spent time to make sure [the complexes] looked inviting and a place anybody would want to live. I appreciate it when people do something like that. It makes everybody feel good about where they live.

– Jennifer Grassham

Executive Director Economic Development Corporation of Lea County

THE ECONOMICS OF BROADBAND IN COMMUNITY-STEERED POLICIES

Nowhere is the stigma of falling behind more salient than in the broadband discourse.

The value of integrating rural communities in digital societal and economic spaces has been summarily reduced to economies of scale, condemning these communities to a digitally disabled state. Lea County’s policymakers decided to reject this end-stage proposition and turned inward to bootstrap tactics that move them incrementally closer to erasing the digital divide. The FCC’s latest Broadband Progress Report indicated that Lea County’s broadband adoption rate approached 93.2% in 2019. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s Airband Initiative data repository disputes this coverage level, suggesting that the FCC’s rate is considerably inflated.14 Microsoft projects the broadband rates to be much lower, at 53.6%.15 Suppose Microsoft’s tremendous undertaking is an indication that its estimates are more reliably robust than the FCC’s. In that case, broadband inequality should take center stage in Lea County’s policy agenda to improve the quality of life for thousands of households. Leaco Rural Telephone Cooperative, Inc. (Leaco), like many other rural-based telephone cooperatives, has vigorously responded to households’ broadband needs.

Leaco delivers internet services in an inverted economic cost funnel that severely delimits broadband access, resulting in broadband blackholes wherein residents have virtually no internet connectivity.16 Despite these exigent circumstances, the company managed to prototype funding strategies to overcome extraordinary cost barriers and deliver reliable, high-speed internet to Hobbs and its surrounding small-scale communities. Leaco has scaled numerous fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) projects over the last ten years. CEO David Jimenez counts the company’s successful attempts to expand fiber delivery to more rural residents among its impressive achievements.

Loans from Rural Utilities Service programs via the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) have played an instrumental part in Leaco’s capital stack to finance the buildout of fiber connectivity over vast geographic expanses. The cooperative recently qualified for a ReConnect funding award. This package combines loans and grants to subsidize broadband buildout in high-need service areas; the company’s allotment is 75% grant and 25% company-sourced investment. CEO Jimenez intends to finish FTTH projects in the outer lying regions of Tatum, located 10 to 15 miles outside of the town’s core.17 The company is currently working with the Economic Development Authority to launch other FTTH projects in socially distressed communities like the cities of Jal and Eunice. Despite Leaco’s exceptional triumphs in delivering gold-standard fiber to small-town rural households and area schools, the company faces scale disadvantages that hinder its ability to effectively compete for federal loans and grant subsidies.

Competition from large incumbent internet service providers means fewer funds for small, missiondriven cooperatives like Leaco and the high-impact FTTH projects such companies design. Even when cooperatives win federal funding bids, competition for scarce contractor resources and raw materials (exacerbated by pandemic supply chain issues) drives up project costs in ways that could diminish the overall value to end users. Serving families and communities motivates Leaco to push the bounds of fiber delivery, and funding goes a long way in supporting this work. The torrent of federal funding to support broadband infrastructure released through the American Recovery Plan Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and still more funding planned in the proposed Farm Bill of 2022 should in theory be helpful. Counterintuitively, however, small cooperatives routinely encounter an array of hurdles: administrative encumbrances to access the morass of funding streams; and various blockades following from well-intentioned but poorly designed programmatic rules that can lead to counterproductive outcomes in the neediest communities. USDA must examine its programmatic paradigms and seriously consider implementing less burdensome requirements, such as by adopting alternative lending standards or service tests that diminish the size penalty for cooperatives working in difficult-to-serve rural markets. Aligning federal award programs with the scale and durability of community impact would level the playing field for Leaco and other critical cooperatives working to reduce broadband inequalities. In CEO Jimenez’s words: “Cooperatives have always stepped into the breach and they’ve done it not for a dollar. They’ve done it for their families.” Broadband may not make straightforward financial sense, but for Leaco, it has always made community sense.

CREATING A RESILIENT RURAL FUTURE IN LEA COUNTY

Lea County’s place in rural America is a majority Hispanic community that has secured its position in the energy economy.

The county’s future depends on its ability to adapt to a rapidly changing world eager to embrace a carbon-neutral EnergyPlex. Lea County is committed to playing a central role in this post-carbon economy with innovative contributions to the energy value chain. The county believes it can become a leading plastics producer for electric vehicles. Whatever the future holds for Lea County, the federal government should be there to work with the county in developing its plans. USDA in particular should be a partner in this work.

But federal assistance must fit within Lea County’s established culture of shared decision-making. Centering community is an essential step in the community participatory framework. But it is just that—one step. The county’s culture is built on a participatory framework where local collaborators play leading roles in translating abstract visions into lucid policies, actively participate in these policies’ execution, and co-direct accountability mechanisms. Lea County’s success is not because of recessionary scars but because people like Ms. Carrillo and CEO Jimenez see themselves and their families’ futures in the county’s progress.

Endnotes

1. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Decennial Redistricting Data.

2. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates.

3. Ibid

4. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 Nonemployer Statistics by Legal Form of Organization.

5. Mayer, Adam, et al. “Fracking Fortunes: Economic Well-being and Oil and Gas Development Along the Urban-Rural Continuum.” Rural Sociology, vol. 83, no. 3, 2018, pp. 532–67, https://doi.org/10.1111/ ruso.12198.

6. “America’s Oil Producers in Decline.” The Economist, 24 Nov. 2014, https://www.economist.com/ news/2014/11/24/americas-oil-producers-in-decline. https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/ local_news/oil-community-hobbs-tries-to-break-boom-bust-cycle/article_bd9f3e0e-5a46-560c-839a- 4add5c4e2b3f.html.

7. “U.S. Oil Production Growth in 2014 Was Largest in More than 100 Years.” Today in Energy, U.S. Energy Information Administration, 30 Mar. 2015, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=20572. b. Rapier, Robert. “How The Shale Boom Turned The World Upside Down.” Forbes, 21 Apr. 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/rrapier/2017/04/21/how-the-shale-boom-turned-the-world-upside-down/?sh=3e3b650577d2. c. https://www.fool.com/investing/2016/12/17/what-happened-to-oil-prices-in-2016.aspx.

8. Autor, David and A. F. Salomons. “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018*.” (2021).

9. http://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2009a_bpea_hamilton-1.pdf.

10. https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2012/recession/pdf/recession_bls_spotlight.pdf.

11. Henry-Nickie, Makada. “Economic Dynamism Thrives in America’s Minority Communities.” Brookings, 9 Mar. 2022, http://www.brookings.edu/research/economic-dynamism-thrives-in-americas-minority-communities/.

12. Parker, Emily, et al. “Do Federal Place-Based Policies Improve Economic Opportunity in Rural Communities?” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, vol. 8 no. 4, 2022, p. 125- 154. Project MUSE https://muse.jhu.edu/article/855653.

13. https://healthcaredesignmagazine.com/projects/first-look-covenant-health-hobbs-hospital/

14. https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/2020-broadband-deployment-report

15. Microsoft: https://github.com/microsoft/USBroadbandUsagePercentages

16. Term coined by Broadband Delivery UK to describe areas where customer do not have access to fixed or wireless internet connections.

17. https://www.usda.gov/reconnect/round-two-awardees

Acknowledgments:

We wish to thank Google.org and Walmart Foundation for their generous support. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of donors. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

The following people contributed significantly to the development of this case study: Regina Seo, Samantha Elizondo, Yeaye Stemn, and Coura Fall. The author thanks the Lea County community for its generous support of this project and wishes to acknowledge GotSafety, New Mexico Junior College’s Department of Allied Health and Nursing, the Economic Development Corporation of Lea County, and Leaco Rural Telephone Cooperative.

ABOUT THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.