How place governance impacts the civic potential of public places

Editor’s note: This brief is part of a three-part series which examines the economic, social, and civic impacts of public space investments in Albuquerque, N.M., Buffalo, N.Y., and Flint, Mich.

Introduction

State and local governments are in a unique fiscal position: After over a year of pandemic-related revenue shortfalls, they are receiving $350 billion in aid to respond to the public health emergency, support workers and businesses, fund infrastructure improvements, fill revenue declines, and support nonprofits and place-based entities to fulfill the broad mandates of the American Rescue Plan. This budgetary lifeline provides cities with the largest fiscal boost in decades—giving them an opportunity to launch transformative investments to rebuild more equitable and sustainable cities.

This comes after decades of deferred public maintenance in many places for critical community infrastructure, such as public parks, streets, and neighborhood business districts.[i] During periods of relative underinvestment, place governance organizations—including Main Street programs, intermediary organizations, business improvement districts, and place-based philanthropies—have often stepped up to bridge the gap between community needs and available public resources, particularly in the governance and management of public spaces within commercial districts.

As cities seek to recover more equitably and leverage their budgets to benefit more people, it is critical to understand how place-based investments—such as physical improvements to the public realm, district-based revitalization strategies, and events and public space activations—can bring about a more equitable economic recovery, and the role place-based nonprofits and other stakeholders play in the governance of these critical investments.

This brief seeks to explore some of these questions through the lens of public space[ii] investments—examining the relationship between the governance and management of public spaces and the civic benefits such places may produce. It does so by summarizing findings from in-depth data collection in three cities (Flint, Mich., Buffalo, N.Y., and Albuquerque, N.M.) and centering the voices of residents, small business owners, and community-based stakeholders to document the nuances of how place governance can shape the ways people interact with, experience, and benefit from public places.

Defining place management and place governance

Place management: Place management refers to the day-to-day operations of public spaces, consisting of activities ranging from maintenance (i.e., keeping places “clean and safe”), events, marketing, decorations, and beautification to “higher-order” goals such as business retention and recruitment, development projects, and advocacy efforts.[iii]

Place governance: Governance, on the other hand, refers to the “who” in who is making decisions and how they relate to the people they govern. “Place governance” often refers to a shift from the public sector exerting control of places to a hybrid structure in which governmental and non-governmental actors collaborate and share control and influence.[iv]

Place governance and management: Unpacking the ‘hybrid’ model of stewarding public spaces

How places are managed and governed impacts their programming, financial sustainability, and community benefits. Yet, place governance remains a largely underexplored input into the community impacts that public spaces generate.

Traditionally in the United States, parks departments built, operated, and maintained public parks, but as city investment in these public assets declined in many places, cross-sectoral partnerships became increasingly important for their financial sustainability. These cross-sector partnerships and hybrid governance models bridge the gap between community needs and public resources—often relying on coordination between the public sector (local government), private sector (business owners, property owners, and real estate developers), nonprofit organizations (Main Streets and other place-based nonprofits), and the philanthropic community to provide access to and maintenance of public spaces.[v]. Certain place governance entities, such as Main Streets and business improvement districts, have a geographic focus to support neighborhoods or central business districts and thus help design, activate, and maintain public spaces to foster economic activity and bring foot traffic to small businesses—from parks to plazas to parklets to streeteries.

However, there are equity concerns around some hybrid place governance models, with critics asserting that the quasi-privatization of public assets can prioritize commercial interests over residents, divert dollars from certain neighborhoods, and heighten place-based disparities because the services these place governance arrangements provide might not be accessible in under-resourced places.[vi] Equity concerns are heightened for people without housing, as some argue that place governance from non-public-sector actors often excludes those without homes from public spaces through policy advocacy, surveillance, and policing practices.[vii]

Critics of hybrid governance structures argue that they must take into account not only who is at the table when it comes to decisionmaking, but “who is setting the table”—contending that public spaces designed and managed by narrow interests for an “average user” are likely to become exclusive places.[viii]

Research has found that when hybrid place governance structures and cross-sectoral partnerships are intentional about power relations within a community, they can generate positive civic outcomes.[ix] The cross-sectoral governance of public spaces can help build the capacity of smaller community groups to drive community-led revitalization goals, offer greater opportunities for residents to take on leadership and management opportunities within public spaces, and build resident capacity to take part in broader neighborhood advocacy outside the boundaries of public spaces themselves.[x] Research has also found that when place governance entities meaningfully involve community members in the planning of public spaces, such engagement helps generate a sense of community and ownership, which in turn contributes to greater use of public spaces.[xi].

By virtue of increasing access to and quality of public spaces themselves, place governance entities can also support communities’ civic well-being. Research finds that people who live in close access to parks are more likely to report that they trust their neighbors and believe community members are willing to help each other.[xii]. Moreover, research indicates that public spaces can provide a “democratic forum” for people to gather[xiii]—providing an important location for cross-cultural exchange and where negotiations of belonging and power can occur.[xiv]

Given evidence on the civic impact of public spaces, efforts such as Reimagining the Civic Commons seek to encourage government agencies, residents, nonprofits, community advocates, and foundations to co-create and overhaul practices and policies in their city to invest in public spaces.[xv] Through this effort, Reimagining the Civic Commons strives to measure the civic impacts of public spaces through three primary indicators: “increased public life” (measured through hourly and weekly visits to a particular public space); “stewardship of place” (measured by “acts of support” for a particular site); and “community trust” (measured by the percentage of people who trust others, local institutions, and local government after investment is made).[xvi]

This brief adds to the literature by both examining the relationship between place governance structures (as an input) and civic community impacts (as an outcome). It asks the questions: 1) how do place governance structures impact the civic potential of public spaces?; 2) whose interests are place governance organizations accountable to?; and 3) how can more people benefit from the capacity-building and support services that these governance models can provide?

Methods: Examining public space governance and civic impacts in Flint, Albuquerque, and Buffalo

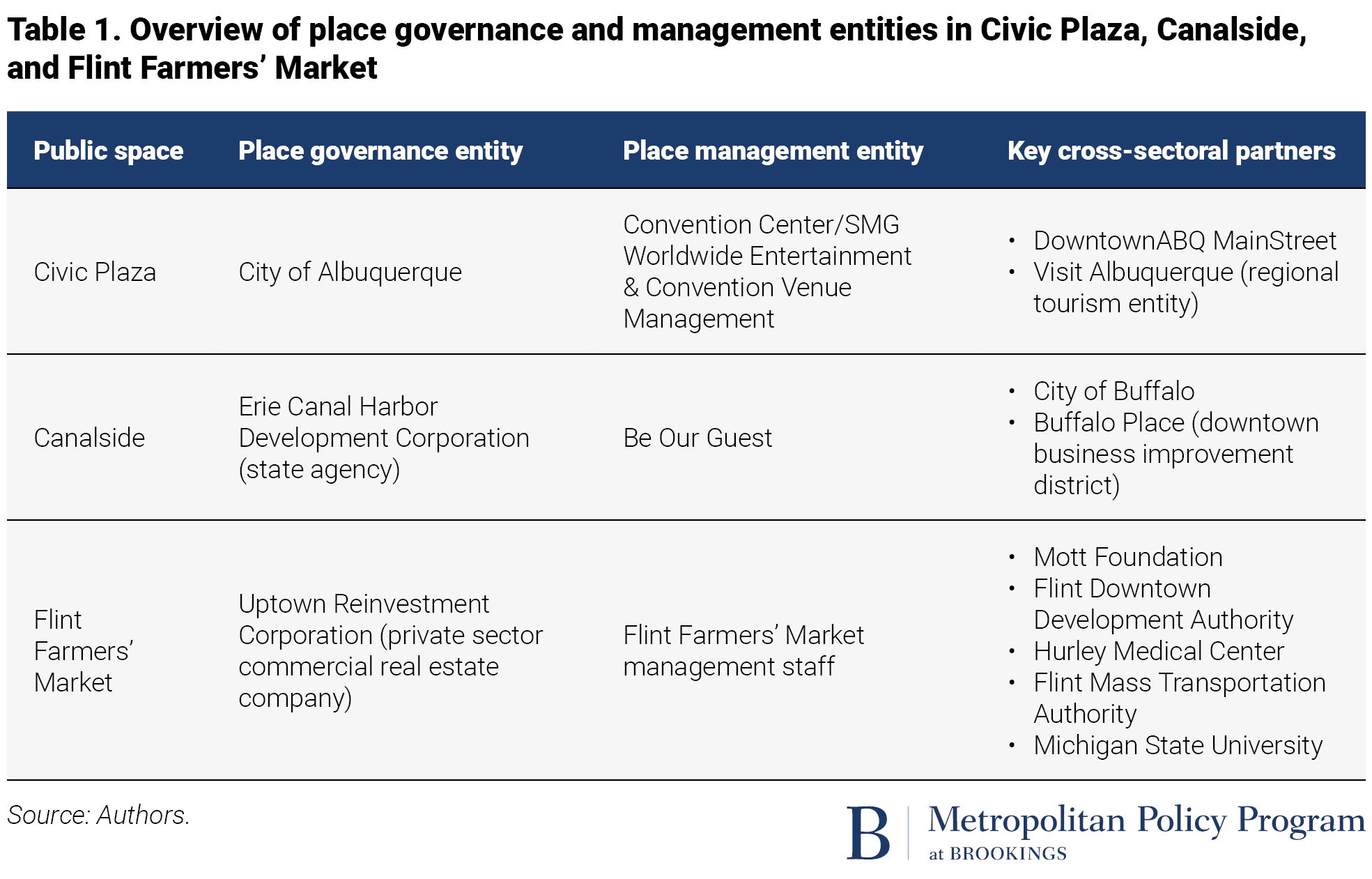

The Brookings Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking and Project for Public Spaces conducted on-the-ground research in Flint, Albuquerque, and Buffalo, examining the impact of three downtown public space investments: The Flint Farmers’ Market, Albuquerque’s Civic Plaza, and Buffalo’s Canalside. (For a description of and background on the public spaces, please see the Introduction brief.) Project for Public Spaces had previously conducted placemaking projects in each of the three spaces—which helped facilitate connections to stakeholders on the ground—but had not been involved in the public spaces for a number of years. All 78 interviews and supplemental focus groups were recorded (unless interviewees explicitly requested not to be, in which case detailed notes were taken), transcribed, and coded using a qualitative coding scheme for consistency and quality control.

Overall, we examined the impact of downtown public space investments on three key outcomes of community well-being, including economic, social, and civic outcomes. We recognize the interdependence of economic, physical, social, and civic inputs and outcomes—by investing in one class of assets (for instance, physical, through public space investments), there are interrelated effects on others (economic, social, and civic). This brief focuses on civic outcomes.

Using the Bass Center’s transformative placemaking framework, we examined the extent to which public space investments can help foster civic structures that are:

Locally organized: Supporting place governance structures that are representative of the community, outcome-oriented, and sustained by funding, expertise, and partnerships

Inclusive: Prioritizing the co-creation of initiatives and programming by a wide range of stakeholders that celebrate open and respectful dialogue and operate with transparency and fairness

Networked: Advancing the development of formal networks and organizations within the community while also supporting resident engagement in broader city and regional civic structures

To learn more about the intersections between civic, economic, and social outcomes, please see the other briefs in the series.

Findings

Our research revealed three multifaceted findings, providing new insights into the web of cross-sectoral negotiations needed to sustain public spaces, the impact that place governance entities’ financial sustainability can have on who benefits from public space programming, and the often hidden ways that place governance structures can impact the civic uses of and reactions to public spaces themselves.

Finding #1: A complex and sometimes precarious web of cross-sectoral partnerships and negotiations undergirds the sustainability of public spaces

All three cities relied on cross-sectoral partnerships to fund, manage, and govern the public space investments, and each model had its own nuances and political tensions that impacted the day-to-day realities of each space.

At the time of our research, the city of Albuquerque owned and governed Civic Plaza but contracted place management to the Convention Center’s private management firm, SMG. This shift in management occurred after decades of limited public investment in and activation of the space; Civic Plaza previously lacked proper lighting, activation, and programming due to limited resources and lack of management, and the shift to SMG represented the first time the public space had been actively programmed in decades. However, some respondents believed this management structure led to the prioritization of commercial rather than community interests within the space and exclusionary tactics toward people experiencing homelessness. One public sector stakeholder hinted at the tension many residents shared, telling us, “They’ve subcontracted that [public space management] to the Convention Center. It’s like having a big huge public space being totally managed by a corporation.”

At the time of our interviews, the city was in the process of regaining management responsibilities from the convention center as part of the mayor’s efforts to leverage placemaking to spur economic development (see “The inclusive economic impacts of downtown public space investments”). However, stakeholders were also skeptical of the city’s ability to upkeep the Plaza for community benefit. “The city is taking over a lot of the management at least the day-day maintenance of the plaza,” one downtown stakeholder told us. “So that will be interesting to see how that works…The city doesn’t have the greatest reputation of getting things done.”

In Buffalo, the governance of Canalside was shaped by legal negotiations between the state and city. Initially, the state’s New York Power Authority provided 20 acres of the waterfront for the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation (ECHDC) to redevelop for Buffalo’s revitalization. Then, in 2014, the state bought an additional 400 acres on the outer harbor—half of which is reserved as a state-run public park.

Tensions and questions regarding state and city ownership remain, with one university stakeholder telling us, “Why did it take 37 years to get a waterfront revitalization plan done? The answer is the politics and the mix of ownership across the spectrum of our waterfront…It took so long and so much public money from the state as opposed to the city investment, there’s a sense of ownership and responsibility that maybe is bigger than the city. That’s a collision.”

The Buffalo city stakeholders we spoke with echoed these tensions. “There are some issues with land ownership,” one public official said. “What’s over state purview? What’s in city purview? Are those two singing together, talking together? Are they coordinated?…There is a line, right? And it’s not a clear delineation, yet.”

It is possible that the state-led governance structure contributed to the disconnect some Buffalo residents reported feeling toward Canalside. “There’s something about [Canalside],” one focus group participant told us. “It just seems like it’s a place that is far from the city…I think a lot of people in the city see Canalside as Canalside, not part of the city.”

Other cross-sectoral efforts are underway to connect Buffalo residents to the waterfront, including a partnership between the city and the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation to revitalize the nearby LaSalle Park to enhance waterfront access for Buffalo’s Lower West Side residents—leveraging significant foundation support to “democratize access” to waterfront parks. These investments are being paired with a $10 million investment in a place management “Conservancy” to preserve the long-term sustainability and inclusive governance of the park, while the city maintains basic maintenance, permitting, and security.

In Flint, a robust cross-sectoral partnership between the Uptown Reinvestment Corporation (URC), the Flint-based Mott Foundation, and regional anchors such as Hurley Medical Center and the University of Michigan made the Flint Farmers’ Market possible. URC’s role as a place governance entity began due to diminished public sector capacity: “It used to be a city owned market and the city didn’t have the resources, of course, to keep it up,” one anchor institution stakeholder explained. “So [URC] was like, ‘We’ll run it on behalf of the city, and help finance it and keep it on its feet.’” But none of the revitalization could have occurred without the Mott Foundation, which helped spearhead the creation of a larger Health and Wellness District downtown

“The market really is at the center point of this health and wellness district that the foundation has provided millions of dollars to build up and to create an atmosphere where people in this community would feel safe,” a foundation stakeholder told us. “The foundation’s goal is to build this all up and then to hopefully build enough economic momentum…so that the foundation doesn’t have to play that big of a role in economic development anymore.”

Each governance model—whether sustained through public-private partnerships, partnerships across multiple levels of public sector governance, or private-foundation partnerships—represents the spectrum of negotiations that localities must navigate to ensure the funding and maintenance of public space investments absent public management. Each also had their own unique impacts on community relations within the space.

Finding #2: The capacity of place governance entities shapes their ability to offer inclusive, community-centered programming

The strength and sustainability of public space governance has implications for the programming offered and the extent to which spaces can offer community-centered resources.

In Buffalo, the significant weight of state investment in Canalside necessitated programming within the public space in a way that could attract revenue to fill budget shortfalls, rather than solely community-based events. “The overall Canalside financial picture is that there is a significant gap annually that the state subsidizes,” one ECHDC stakeholder told us. “We are continually working on the financial model and trying to lessen the expenses and increase the revenue sources…We’d like to obviously break even.”

ECHDC connected this financing gap to the programming offered in the space itself, telling us that until the development is financially sustainable on its own, they had to rely on events that could generate revenue, as well as concessions. Our separate focus groups with residents revealed that this emphasis on charging for events raised significant inclusion concerns and prevented some lower-income residents from visiting Canalside. In this case, financial constraints and the state’s larger development plan impacted the ability of the public space to be used for more community-centered programming as opposed to revenue-generating events.

In Flint, stakeholders attributed the Farmers’ Market’s inclusivity and community connectivity to the support of private and foundation stakeholders. As one place manager told us, “What’s not necessarily understood by the general public is how much [private] money was invested…into that space.” Without URC funding, Mott Foundation support, and events, the market would not have been able to stay open and operate with its annual budget shortfall. This cross-sectoral support and private financing directly impacted the community-centered programming the market was able to offer, including incubator space, commercial kitchens, entrepreneurship training, Double Up Food Bucks, and a mobile market (described further in the economic and social briefs).

Vendors within the market spoke to the importance of the management entity in supporting them and helping them grow their business: “What really helps is the access that we have to the management here,” one vendor told us. “I’ll sit down with them and talk to them about everything…They hold a space for all the vendors to be able to voice concerns or try to help out in any one way.”

In Albuquerque, city financial hardships led many residents to notice a sizeable decline in Civic Plaza’s activation and public events. “I think the most important reason why some of the Civic Plaza events stopped was because of recession, and they just didn’t have the money,” one focus group participant told us. “There was no reason to use that as a corridor anymore, and so it functioned…as a place to loiter.”

The varied financial outlook and governance models of each space largely influenced the extent to which public spaces could be used as a hub for community services, as a revenue-generating model, or even as a “place to loiter.”

Finding #3: The often hidden dynamics of place governance can influence the civic uses of and responses to public spaces

Aside from the programming offered within each public space, the political, funding, and management dynamics associated with various place governance structures also seemed to influence the civic uses of the spaces themselves.

In Albuquerque, for instance, when Civic Plaza was not actively being programmed, the public used the space to protest or communicate political messages to city officials. Part of this was because of its geographic location as a central hub downtown. “[Civic Plaza] is the civic space for which marches start or end,” one public sector official said. “It’s the heart of Albuquerque, and that is where people know to go to vocalize their opinions.”

Yet another reason was its ability to communicate public disconnects to the city. Another public official told us, “It’s interesting because, for the past year, there’s been chalk messages all over Civic Plaza…little guerilla installations of messaging with chalk for the mayor.”

In Buffalo, Canalside was primarily used as a space for families and events. However, its role as a state-governed strategy for economic revitalization led to its own civic implications. At times, this role united the public in opposition to corporate development interests; first with the public outcry against the Bass Pro Shops development (see the series Introduction for more detail), then with a community-led organizing attempt to negotiate a legally binding Community Benefits Agreement for the revitalization effort, and presently, with public feedback opposing private development that could restrict public access to the waterfront.

“The irony is that Canalside, when it was originally Bass Pro, unified people against something,” one public sector official told us. “The new vision of Canalside was by the community—a lesson for all of us of listening to the communities needs and desires.”

Currently, the community is voicing its discontent again with the development of waterfront, including the Outer Harbor. As one ECHDC stakeholder explained, “The public has told us, ‘We really don’t want buildings here. We don’t like this 21-story [building]…We want green space, we want to be able to walk and bike.’ There’s nothing we can do about that. That’s a private development…So we put in a bike park and all that kind of stuff…That’s largely from listening to the public.” This negotiation between state officials and the public demonstrates the usage of spaces as an avenue for direct civic engagement and power-brokering in public decisionmaking.

In Flint, the Farmers’ Market largely served as a hub for local organizations and nonprofits to reach city residents. Multiple stakeholders echoed this sentiment, with one resident saying, “It’s recognized as being a place that you can share information…Whether you’re part of the government, part of a nonprofit, you can get information out there in front of people so that they know what the public resources are.” Market staff agreed, with one telling us, “Everybody always wants to be here ’cause they know it’s an easy spot to reach out to residents of Flint.”

These varied civic impacts—from Civic Plaza serving as a hub for protests and social demonstrations against the city, to Canalside and the waterfront providing residents with concrete ways to shape public and private development, to the Flint Farmers’ Market creating a space for interaction and information-sharing between residents and nonprofits—demonstrate the civic potential of public spaces, but also how the complex web of actors and organizations involved in management and governance can influence the civic impacts of these public assets.

Conclusion

As cities seek to recover more equitably from the COVID-19 economic crisis and ensure that often overlooked priorities such as community infrastructure are equitably funded,[xvii] it is critical to examine the place-based entities and intermediaries that are often behind these efforts at the local level—and ensure their capacity to govern inclusive public spaces.

Our research shines light on the diverse array of public, private, and nonprofit leaders that govern the public space investments communities rely upon, and the web of interactions between these groups that can shape the potential of public spaces to drive civic engagement and community connections. These findings raise more questions than answers at times, but at their core, they demonstrate the dedicated network of civic leaders seeking to support public space access under tight financial constraints.

As cities and places seek to strengthen inclusivity within place governance practices, there are promising national models to follow, including Boston’s Place Leadership Network working to shift power imbalances within the city; the inclusive place management structures within San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza; and Atlanta’s place-based social service provision for people without housing within Woodruff Park. Public spaces will be a critical component of economic recovery, and it is crucial to understand the importance of the local organizations and actors working to strengthen these civic assets.

Cover photo: Buffalo Waterfront. Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

The authors thank Joanne Kim for her excellent research assistance on this series. They express their sincere gratitude to the community stakeholders who participated in research interviews and focus groups. They also thank Lola Bird, Lavea Brachman, Karriane Martus, Steve Ranalli, Nate Storring, and Jennifer S. Vey for their review of various drafts of the series. Any errors that remain are solely the responsibility of the authors.

[i] Urban Land Institute, Successful Partnerships for Parks: Collaborative Approaches to Advance Equitable Space, 2020: https://knowledge.uli.org/en/Reports/Research%20Reports/2020/Successful%20Partnerships%20for%20Parks

[ii] Please see the Introduction for our definition of “public space.”

[iii] Yanchula, J. Finding one’s place in the place management spectrum. Journal of Place Management and Development, 2007, 1(1), 92-99: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/17538330810865354/full/html.

[iv] Dempsey, N., & Burton, M. Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2012: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1618866711000732. Zamanifard, H., T. Alizadeh, T., and Bosman, C.. Towards a framework of public space governance. Cities, 2018, 78, 155-165: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275117302305.

[v] Urban Land Institute, Successful Partnerships for Parks: Collaborative Approaches to Advance Equitable Space, 2020: https://knowledge.uli.org/en/Reports/Research%20Reports/2020/Successful%20Partnerships%20for%20Parks.

[vi] Dempsey, N., & Burton, M. Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2012: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1618866711000732; Zamanifard, H., T. Alizadeh, T., and Bosman, C.. Towards a framework of public space governance. Cities, 2018, 78, 155-165: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275117302305. Hoyt, L., & Gopal‐Agge, D. The business improvement district model: A balanced review of contemporary debates. Geography Compass, 2007: 1(4), 946-958: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00041.x.

[vii] Hoyt, L., & Gopal‐Agge, D. The business improvement district model: A balanced review of contemporary debates. Geography Compass, 2007: 1(4), 946-958: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00041.x.

[viii] Agyeman, J. Interculturally Inclusive Spaces as Just Environments, Social Science Research Council, 2017: https://items.ssrc.org/just-environments/interculturally-inclusive-spaces-as-just-environments/

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Walker, C. The Public Value of Urban Parks. Urban Institute, 2004: http://webarchive.urban.org/publications/311011.html; Gaynair, G., M, Treskon, J. Schilling, and Velasco, G. Civic Assets for More Equitable Cities. Urban Institute, August 2020: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/civic-assets-more-equitable-cities; Knight Foundation. Measuring Progress Toward Downtown Revitalization and Engaging Public Spaces: A Review of Existing Research. August 2020: https://knightfoundation.org/reports/measuring-progress-toward-downtown-revitalization-and-engaging-public-spaces-a-review-of-existing-research/

[xi] Project for Public Places. The Case for Healthy Places, 2016: https://www.pps.org/product/the-case-for-healthy-places

[xii] Center for Active Design. Assembly: Civic Design Guidelines. 2018: https://centerforactivedesign.org/assembly;

[xiii] Woolley, H., Rose, S., Carmona, M., & Freedman, J. The Value of Public Space: How high quality parks and public spaces create economic, social and environmental value. N.d.: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/the-value-of-public-space1.pdf.

[xiv] Rios, M. (2013). From a Neighborhood of Strangers to a Community of Fate: The Village at Market Creek Plaza. In Transcultural Cities: Border-Crossing and Placemaking ed. Hou, J.

[xv] Gaynair, G., M, Treskon, J. Schilling, and Velasco, G. Civic Assets for More Equitable Cities. Urban Institute, August 2020: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/civic-assets-more-equitable-cities.

[xvi] Marquis, Bridget. The Social Impact of Public Space: A Case for Measurement, Philanthropy Journal: July 29, 2019: https://pj.news.chass.ncsu.edu/2019/07/29/the-social-impact-of-public-space-a-case-for-measurement/.