From relief to recovery

What to know

As the nation recovers from the pandemic, the strategic lens for small business support will shift from averting destruction to making strategic investments in entrepreneurship ecosystems and small business growth strategies. Those longer-term investments typically try to address one of three broader economic objectives: growing jobs, addressing racial disparities in asset ownership, and investing in underserved neighborhoods and commercial corridors. Before turning to strategic responses, below is a brief recap of the evidence on the role of small businesses in each of these areas.

1. Jobs: Not just creation, but quality and accessibility too. The economic literature is clear that young businesses—most of which are small—are the engines of net job creation in any local economy.[i] Every year, a new cohort of startups emerges and creates more net jobs than older, larger businesses. But most of those businesses and jobs are gone within five years. Given this mortality rate, 43 entrepreneurs must start a business to yield a single business that employs someone 10 years later, and that one business will employ nine people on average. As one study concluded, “a small proportion of high-performing firms drive the majority of innovation, wealth creation, and new job generation, while most firms, including the median small business and the median start-up, have only a marginal impact.”[ii] As a result, economic development strategies often focus on building ecosystems of support for startups positioned for very rapid growth. That is not misguided, but it only accounts for a very small share of small businesses, often focused on breakthrough technologies. This approach leaves out a range of Exporters (or even Local Suppliers) with the potential to incrementally create jobs if given the proper supports.

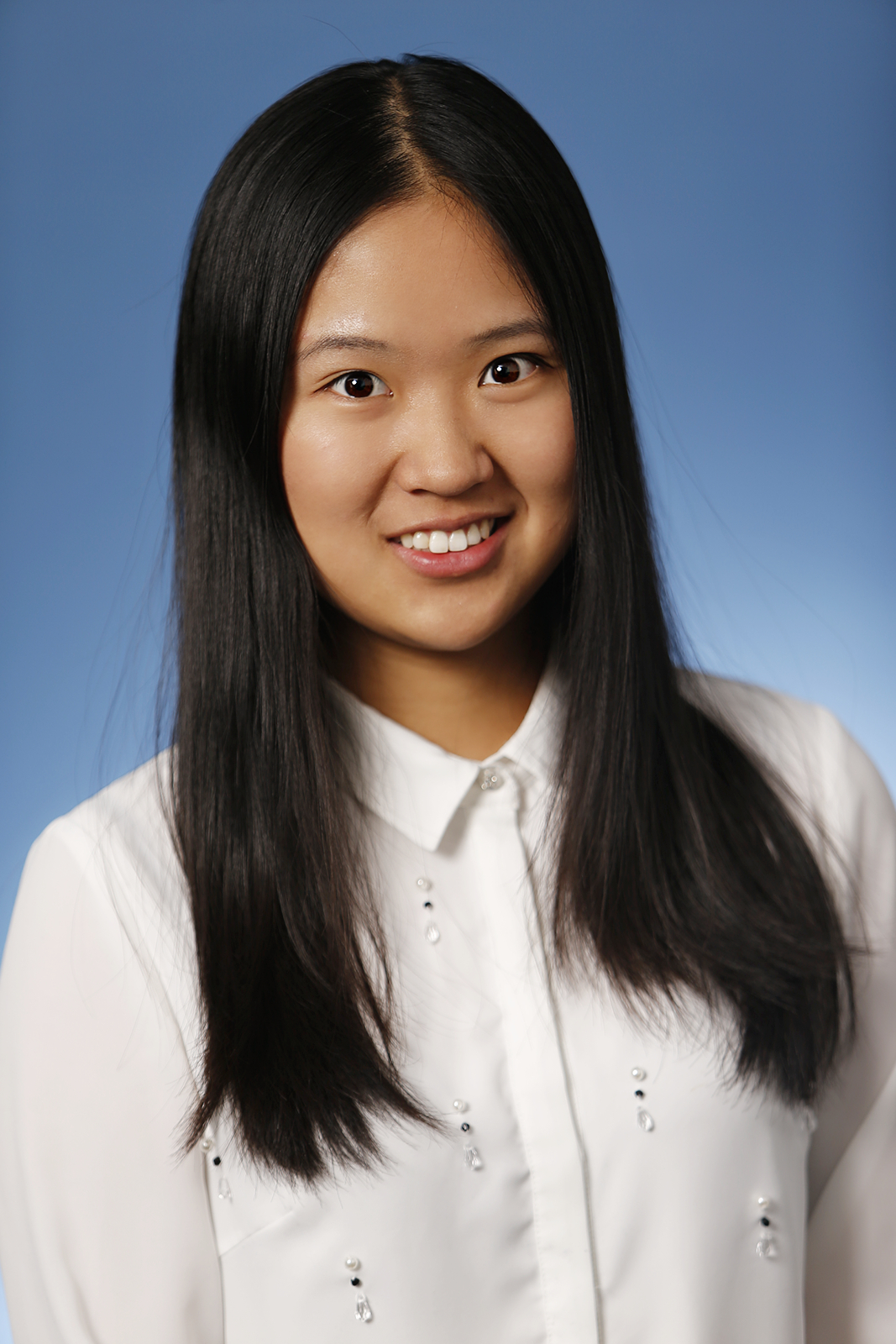

Additionally, the quality and accessibility of jobs—in addition to their creation—is an important consideration. Along these lines, small business segments vary in the wages they pay (a key metric of job quality) and in the education and skills they require (a key metric of job accessibility). For example, Exporters pay the highest wages and, not surprisingly, have a lower share of jobs that are accessible to workers without a four-year degree. Main Street small businesses account for the most jobs, and a higher share of those jobs are accessible to those without a four-year degree. Local Suppliers offer a combination of relatively high average wages and a high share of jobs that do not require a four-year degree. As local leaders aim to support small businesses to catalyze a jobs-filled recovery, they must be clear-eyed about the varying roles that different types of small businesses play in generating family-sustaining and accessible jobs.

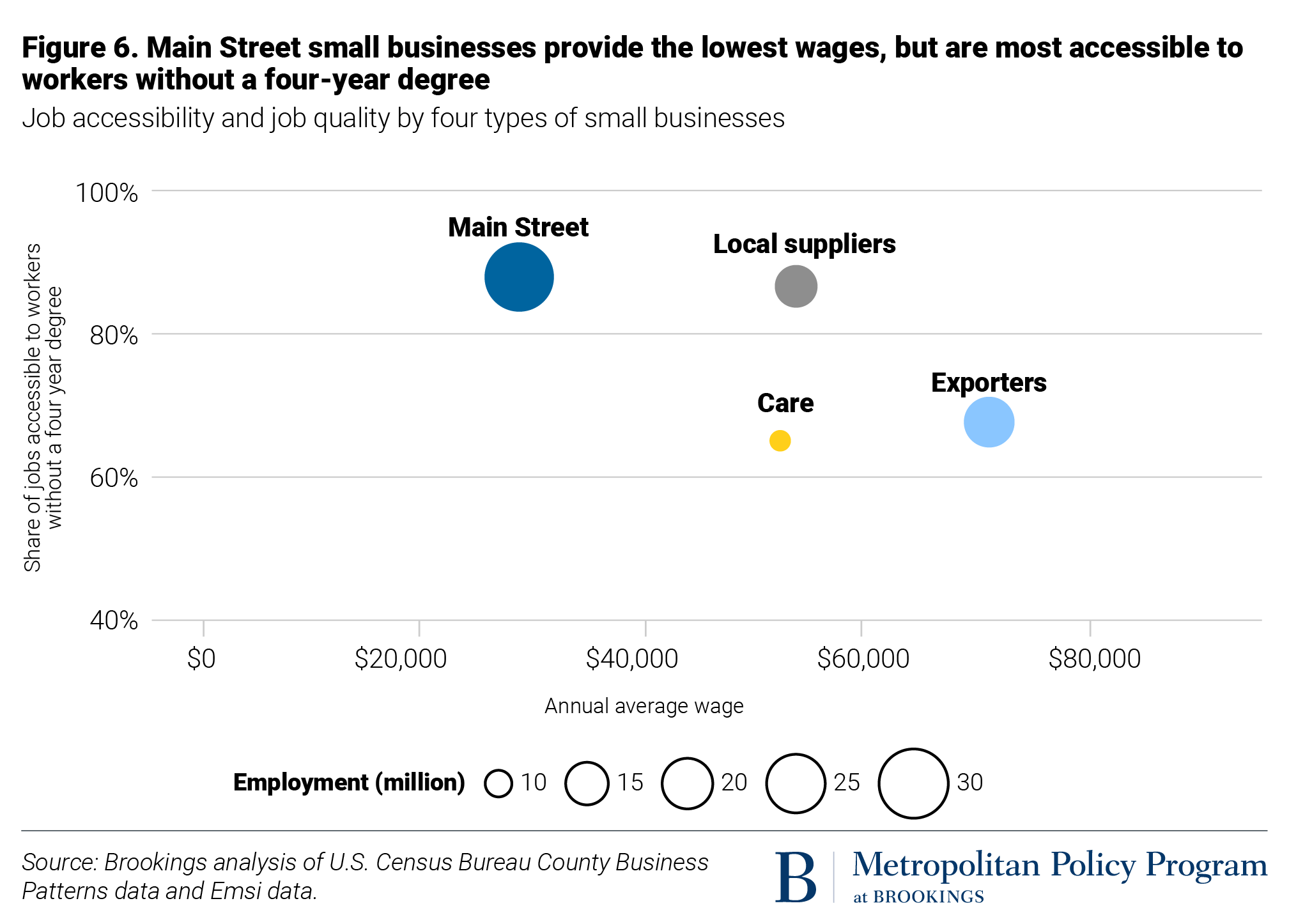

2. The racial wealth gap: A “leveraged bet,” not a “sure ticket.” The ownership, profitability, and physical locations of small businesses all are influenced by the nation’s legacy of systemic racism, discrimination, and economic and racial segregation. At one level, a wide body of research shows that structural factors limit people of color—particularly Black and Latino or Hispanic entrepreneurs—as they consider starting and growing businesses, including disparities in educational attainment, personal wealth, and access to capital.[iii] Importantly, these disparities represent structural impediments to entrepreneurship and, per Gallup’s research, do not reflect the inherent entrepreneurial abilities or interests of different groups.[iv] Currently, people of color represent about 40% of America’s population, but only 18% of the nation’s 5.7 million business owners with employees.[v]

Racial inequality certainly limits entrepreneurship, but can entrepreneurship be a path to addressing racial inequality in the wake of COVID-19? Yes, suggests a seminal report by the Association for Enterprise Opportunity, which found, “Black business owners are wealthier than their peers who do not own businesses, and business ownership creates new wealth faster compared to wage employment.”[vi] More recent research finds that entrepreneurship should be viewed as a “leveraged bet”—not a “sure ticket” to wealth mobility.[vii]

Across all racial groups, entrepreneurs experience upward wealth mobility when they succeed but downward wealth mobility when they fail. Black Americans start businesses at higher rates than white Americans, but Black-owned small businesses are more likely to close within four years than white-owned small businesses (due to the structural barriers outlined above). These higher failure rates result in a greater likelihood of downward mobility for Black entrepreneurs as compared to white entrepreneurs. [viii] In other words, it will be hard for entrepreneurship strategies to close wealth gaps unless they account for the dramatically different starting points in wealth between white Americans and Black and Latino or Hispanic Americans. The typical Black and Latino or Hispanic household has 32% and 67%, respectively, of the liquid wealth of the typical white household. Even successful Black and Latino or Hispanic small business owners (those that were still in business four years after launch) still have a significant gap in liquid wealth compared to white small business owners.[ix]

Finally, average revenues vary considerably across industry segments. While not a direct measure of potential wealth creation, it is likely that higher-revenue sectors offer a greater likelihood of generating significant wealth for successful business owners. Yet, due to structural factors, entrepreneurs of color face even more barriers to owning businesses in the highest-revenue sectors, disproportionately owning businesses in lower-revenue segments such as Main Street and Care.

3. Neighborhood reinvestment: One lever among many. A third outcome is neighborhood reinvestment. Taking a place-conscious approach to small business development acknowledges that an opportunity structure determined by where one lives does not arise due to market forces or consumer preferences alone, but also from government policies related to zoning, housing development, transportation, and education that diminished the market attractiveness of certain communities—oftentimes, communities of color—relative to others.[x] Where investment has historically been channeled has ramifications for neighborhood-level consumer demand, where small businesses physically locate, and how the perception of neighborhoods influences small business revenues.[xi]

Breaking the cycle of devaluation can bring amenities (especially retail) to neighborhoods that need it, and advance local business ownership so that the fruits of neighborhood reinvestment accrue to local residents.[xii] Yet prior research suggests that while retail development can enhance commercial investment returns, improve housing values, and boost tax revenues, it does not significantly influence the economic prospects of neighborhood residents.[xiii] Given this, small business development should be one lever in broader “community-rooted economic inclusion” strategies that align infrastructure, land use, and housing policies to strengthen commercial corridors and districts.[xiv]

Understanding small business dynamics: As local leaders consider the role of small businesses in inclusive recovery strategies, this interactive module provides them with relevant indicators on the industry and ownership structure of their small business economies.

How to respond

1. Navigate from a “North Star.” As we outline above, local governments could work with and through small businesses to achieve a range of broader economic objectives related to quality job creation, racial equity, and neighborhood reinvestment. Each of these are worthy outcomes and are explicitly referenced in the guidance for how localities can use their Coronavirus Fiscal Recovery Funds. These “North Star” outcomes can help local leaders build a portfolio of small business responses that best address those outcomes. In prior work, Brookings outlined one vision for recovery:

“In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, local leaders will rebuild better, generating higher-quality job and wealth creation opportunities in their local economies that advance racial inclusion.”[xv]

2. Create recovery strategies around key leverage points. Recovery strategies must meet the eligibility requirements stipulated in the American Rescue Plan if local governments want to utilize those federally provided resources. The Treasury Department is still soliciting feedback on its interim ruling on the CFR funds. But beyond eligibility, local leaders should select strategic priorities with the recognition that small businesses operate within regional economic systems. These systems are subject to feedback loops and leverage points, which in turn are influenced by economic, social, and institutional conditions.[xvi] One way to craft recovery strategies is to focus on those leverage points with the greatest potential for positive change in local economic system. While there are countless leverage points that strategies could target, we highlight three that meet the following criteria: a) leverage major resources/policy changes; b) alter existing systems; and c) advance both family-sustaining jobs and racial equity.

Leverage Point 1: State resources

State investment in entrepreneurship-led economic development is the first leverage point. In this section, we draw on the insights from a previous Brookings post on the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) authored by Robert Maxim, Eric Cromwell, Dan Schmisseur, Mark Muro, and Joseph Parilla.[xvii] SSBCI provides $10 billion to states and tribal governments, and it complements existing small business relief programs by giving states more time (10 years) and flexibility to distribute capital.

SSBCI incentivizes states to move capital quickly (states can only receive additional tranches once current funds are lent), inclusively ($2.5 billion is set aside for disadvantaged businesses), and with leverage (a requirement that $10 in private capital be leveraged for every $1 in state-supported capital). Beyond those requirements and incentives, SSBCI can support a range of eligible state programs: capital access, collateral support, loan participation and loan guarantee programs for credit support, and state-sponsored venture capital programs for equity support.

Local actors across government, economic development, entrepreneurship support, and community development should be partnering with states to craft SSBCI strategies that not only deliver capital effectively, but also consider doing so in ways that build longer-term capacity. If designed well, SSBCI could advance family-sustaining jobs and racial equity in several ways.

- SSBCI-supported lending programs can work with mission lenders such as CDFIs and community banks to address the systemic market needs of socially and economically disadvantaged individuals. This could involve launching CDFI-led funds—capitalized by major financial institutions—to support undeserved small businesses with viable products and services but little connection to mainstream finance. For example, the California Rebuilding Fund was seeded by the state and is working with a network of 12 CDFIs to deploy capital to small businesses with fewer than 50 employees.[xviii]

- Venture capital (VC) programs can work with nonprofit venture development organizations (VDOs) and private investors to mitigate capital access challenges for high-growth startups resulting from the extreme geographic concentration of the venture capital industry.[xix] The Treasury Department provided states with $500 million in technical assistance funding, which could be used to provide legal, accounting, and financial advisory services to very small investment management businesses and accelerators so that they can apply to states to manage SSBCI funds, with the goal of spurring more women- and minority-led investment funds. As one example, the Cincinnati-based Hillman Accelerator—which provides capital, coaching, and connections to underrepresented entrepreneurs operating promising tech-driven companies—received an early investment from Ohio’s Third Frontier program. Today, the Black founders of that accelerator run a $50 million investment fund—one of the largest Black-led funds in the country.[xx]

- Beyond SSBCI, localities, states, and tribes could invest in inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystems by leveraging a portion of ARP’s $350 billion in flexible funding contained to put toward small business development centers, incubators and accelerators, worker cooperatives, and other entrepreneurial support. Indeed, recent Treasury Department guidance makes it clear that “technical assistance, counseling, or other services to assist with business planning needs” are an acceptable use of that funding if put toward “businesses with less capacity to weather financial hardship, such as the smallest businesses, those with less access to credit, or those serving disadvantaged communities”—the exact businesses SSBCI targets. In Cincinnati, for example, Mayor John Cranley has proposed a $4 million investment to support the Cincinnati Minority Business Collaborative, a collection of local business development organizations invested in minority business growth, using the city’s federal relief funding.[xxi] In Detroit, Mayor Mike Duggan has proposed an $8 million expansion of that city’s Motor City Match, which incentivizes small business investments in lower-income commercial corridors.[xxii]

Leverage Point 2: Grassroots momentum

A second leverage point is community-based momentum for worker empowerment and job quality improvements. The Fight for $15 has been one of the most powerful worker movements in modern American history. At the start of 2020, nearly half of states and dozens of localities raised their minimum wage.[xxiii] Notably, small business groups such as chambers of commerce, small business associations, and restaurant associations often oppose minimum wage increases. Yet, this historic dividing line requires a rethink amidst newer evidence. Recent increases in the minimum wage in several major cities have not resulted in large employment losses.[xxiv]

The grassroots momentum for enhancing worker pay and stability need not be framed as a battle between workers and small businesses. Rather, as cities and states enact minimum wage increases, they could also invest in intermediaries that provide customized services to help small employers upgrade their management, operations, and human resources capabilities with the objective of improving job quality for workers.[xxv] Evaluations of these interventions have generated promising results, and a small allocation from a local government’s CFR funds (presuming COVID-19 negatively impacted those businesses in some way) could launch and evaluate similar efforts through 2024, when ARP funds must be spent. Examples include:

- Genesis, a pilot project run by the Illinois Manufacturing Excellence Center (IMEC), was designed to improve job quality by integrating “people” guidance (workforce engagement, productivity, employee stability) with “product” guidance (cost reduction, quality improvement, technology adoption) for small- to medium-sized manufacturers. The program was customized for each company, with services determined by surveys and focus groups with frontline employees. Genesis companies reported increased sales, higher job retention, wage gains for workers, and lower turnover.[xxvi]

- HireReach is another model that offers both large and small businesses advanced talent development services. In 2018, Talent 2025, a group of 100 CEOs from the West Michigan region, and West Michigan Works!, a local workforce agency, collaborated to launch HireReach, a three-year initiative that recruits, trains, and advises employers to hire entry-level and middle-skill talent using an evidence-based selection process. Their model increases the accuracy of candidate selection, which in turn strengthens the quality of the employer’s workforce and reduces turnover. It also mitigates biases in the hiring process by using a data-driven approach to assess candidates fairly and objectively. HireReach supports participating employers with a monthly shared learning event called the Community of Practice, as well as with monthly consulting sessions to support individual employers in adopting the evidence-based selection process. Between 2010 and 2018, Mercy Health—which developed the model—employed over 10,000 candidates using this process, reporting a 23% reduction in first-year turnover, a 16% reduction in time to fill, and a doubling of the racial and ethnic diversity of the workforce.[xxvii]

Leverage Point 3: Corporate commitment

The Boston Consulting Group estimates that corporate America has pledged $80 billion to advance racial equity, including to support businesses owned by people of color. There is an inherent skepticism as to if this will be a durable commitment or a passing fad. One way to ensure this rare window creates lasting change is to work with large corporations and anchor institutions to set procurement goals to work with minority-owned businesses—particularly, Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned businesses.

Specifically, local governments, economic development organizations, and entrepreneurship support groups could work with large corporations and anchor institutions to assess their current supply chain with respect to location and demographics; set shared targets for contracting with local suppliers and Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-led suppliers and vendors; and invest in accelerators that build the pipeline of minority-owned businesses to take advantage of these shifts in corporate America’s procurement norms. These investments in capacity can leverage larger philanthropic investment from corporate America, but the larger impact will be generated by shifting corporate procurement to balance community value with shareholder value. Examples of actionable solutions include:

- Cincinnati’s Minority Business Accelerator has a team of seasoned executives—some loaned from larger corporations and financial institutions—that rigorously assess, screen, and strategize with minority businesses (which are considered portfolio companies) to ensure the business is ready to take on new investment or benefit from a contract with a larger corporate customer. The rigor with which the accelerator develops its portfolio ensures that corporate partners (referred to as “Goal Setters”) who desire a more racially diverse set of suppliers have access to an investment-ready set of minority-owned companies. Since its founding in 2003, the accelerator has built a portfolio of 67 minority-owned businesses that have created 3,500 jobs and over $1.5 billion in aggregate annual revenue. Its current goal calls for doubling the average firm size (from $25 million to $50 million), total sales of its portfolio firms (from $1 billion to $2 billion), and total jobs in its portfolio firms (from 3,500 to 7,000) between 2017 and 2022.

- Minneapolis-St. Paul’s Itasca Project, an employer-led civic alliance, initiated an effort in 2012 with the Supply Chain Executive Council (SCEC) to increase procurement spend locally. The SCEC comprises more than a dozen senior purchasing officers from Minnesota’s largest companies, who established “Business Bridge”—an effort to more intentionally direct spend with Minnesota-based suppliers. Business Bridge centered on a set of shared principles and spend goals. SCEC companies spent more than $10 billion with Minnesota-based companies in 2019 – an increase of $3 billion from 2012. Over the past year, the SCEC leaders looked to galvanize a broader group of companies and organizations to prioritize the procurement of products and services from diverse businesses to close economic inequity gaps by creating jobs and wealth. The SCEC is adding the following goals to Business Bridge: increase spend with Minnesota-based diverse businesses by 25% in three years and double their number of participating members over the same period. The impact could be an additional $500 million per year for diverse businesses in their state.

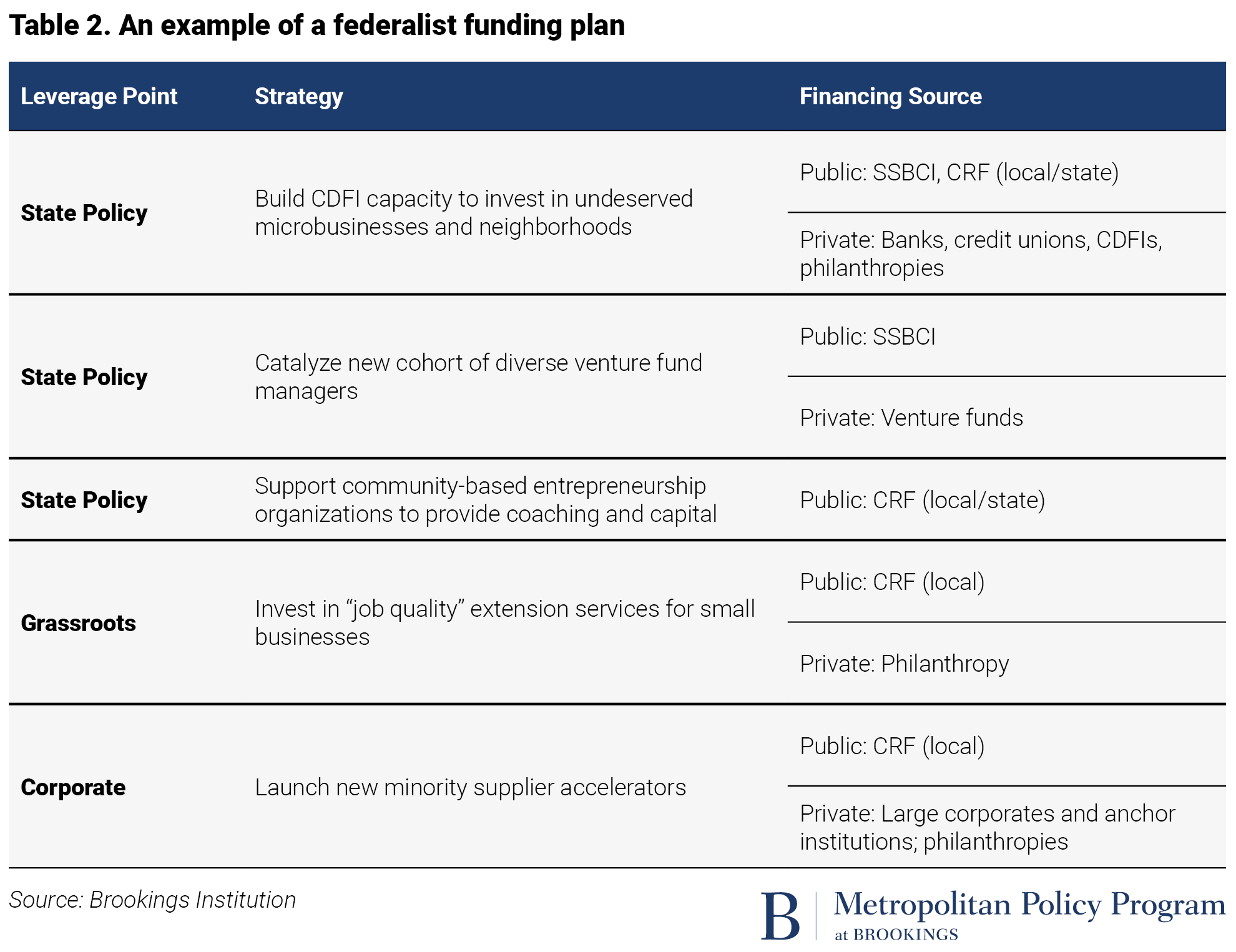

3. Build a federalist funding plan. To date, most mayors, county officials, and governors have outlined broad priorities related to small business support. Once the Treasury Department guidelines on the CFR are finalized, local governments will be able to solidify eligible uses and move to finance and implement strategies. These plans will differ based on economic conditions, institutional capacity, and government priorities. Table 2 outlines one example of a simple federalist funding plan. It maps the financing sources against those strategies that a) can benefit from key leverage points; and b) could be eligible under the current ARP guidelines.

Footnotes

[i] Haltiwanger, John, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda. “Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young.” Review of Economics and Statistics 95.2 (2013): 347-361.

[ii] Paul Nightingale and Alex Coad, “Muppets and gazelles: political and methodological biases in entrepreneurship research.”

[iii] Klein, Joyce A. Bridging the Divide: How Business Ownership Can Help Close the Racial Wealth Gap. Aspen Institute, 2017.

[iv] Rothwell, Jonathan “No Recovery: An Analysis of Long-Term U.S. Productivity Decline”, Gallup, December 6, 2016

[v] Brookings analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Annual Business Survey data

[vi] Gorman, Ingrid. “The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America: Untapped Opportunities for Business Success.” (2017).

[vii] Kroeger, Teresa, and Graham Wright. “Entrepreneurship and the Racial Wealth Gap: The Impact of Entrepreneurial Success or Failure on the Wealth Mobility of Black and White Families.” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy (2021): 1-13.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Wheat, Chris, Chi Mac and Nich Tremper, “Small business ownership and liquid wealth”, JPMorgan Chase Institute, 2021

[x] Love, Hanna, et al. “Community-rooted economic inclusion: a strategic action playbook.” Brookings Institution, 2021.

[xi] Perry, Andre, Jonathon Rothwell, and David Harshbarger. “Five-star reviews, one-star profits: The devaluation of businesses in Black communities,” Notes 71 Brookings Institution, February 18, 2020.

[xii] Dinkins, Reniya, “A community investment trust for Portland, Ore. residents to ‘buy back the block’”, Brookings Institution (2020)

[xiii] Chapple, Karen, and Rick Jacobus. “Retail trade as a route to neighborhood revitalization.” Urban and regional policy and its effects 2 (2009): 19-68. ; Pivo, Gary, and Jeffrey D. Fisher. “The walkability premium in commercial real estate investments.” Real Estate Economics 39.2 (2011): 185-219.

[xiv] Love, Hanna, et al. “Community-rooted economic inclusion: a strategic action playbook.” Brookings Institution, 2021.

[xv] Liu, Amy, Alan Berube and Joseph Parrila, “Rebuild better: A framework to support an equitable recovery from COVID-19”, Brookings Institution (2020)

[xvi] Feld, Brad, and Ian Hathaway. The Startup Community Way: Evolving an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

[xvii] Maxim, Robert, Eric Cromwell, Dan Schmisseur, Joseph Parilla, and Mark Muro, “How cities, states, and tribes can boost entrepreneurship via the American Rescue Plan”, Brookings Institution (2021)

[xviii] California Rebuilding Fund, https://www.connect2capital.com/p/californiarebuildingfund/

[xix] Gines, Dell and Rodney Sampson, “Building racial equity in tech ecosystems to spur local recovery”, Brookings Institution (2021)

[xx] Fouriezos, Nick, “A Power Couple With A $50m Venture Fund For The Overlooked”,OZY (2020), https://www.ozy.com/the-new-and-the-next/a-power-couple-with-a-50m-venture-fund-for-the-overlooked/363654/

[xxi] Wetterich, Chris, “P&G, mayor, business groups want to double number of minority-owned companies in five years”, Cincinnati Business Courier, https://www.bizjournals.com/cincinnati/news/2021/03/25/p-g-mayor-biz-groups-want-to-double-number-of-min.html

[xxii] American Rescue Plan Act, City of Detroit, https://detroitmi.gov/government/mayors-office/american-rescue-plan-act

[xxiii] Lathrop, Yannet. “Raises From Coast to Coast in 2020.” National Employment Law Project (2019).

[xxiv] Kinder, Molly, “Even a divided America agrees on raising the minimum wage”, Brookings Institution (2020); Allegretto, Sylvia, et al. “The new wave of local minimum wage policies: Evidence from six cities.” CWED Policy Report (2018).

[xxv] Donahue, Ryan and Joseph Parilla, “Deploying industry advancement services to generate quality jobs” (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2020).

[xxvi] Genesis companies reported a 55% increase in sales over the course of the two-year program, compared to 37% among IMEC clients that did not participate in Genesis. As a result, 65% of Genesis companies reported retaining jobs, versus 42% of non-Genesis IMEC clients. Significant benefits accrued to workers as well: Annual earnings at Genesis companies increased by 12%, pushing those companies’ wages from 78% to 84% of the industry average. The share of workers making less than $30,000 fell from 34% to 26%. Turnover among the most actively involved companies fell from 5.8% to 3.3%. Ranita Jain and others, “Genesis at Work: Evaluating the Effects of Manufacturing Extension on Business Success and Job Quality” (Washington: The Aspen Institute, 2019).

[xxvii] Dinkins, Reniya, Gabriel Morrison and Sifan Liu, “An evidence-based selection process for equitable hiring in West Michigan”, Brookings Institution (2020)

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

This report is made possible by the Kresge Foundation and the Shared Prosperity Partnership, for which the authors are deeply appreciative. We also want to thank colleagues who provided valuable feedback on the report: Alan Berube, Annelies Goger, Pam Lewis, Tracy Hadden Loh, Rob Maxim, and Mark Muro. The authors also thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Luisa Zottis for layout and design, Alec Friedhoff for his design of the data interactive, David Lanham for his communications leadership, and Jade Arn and Rowan Bishop for help on outreach.