Chapter

04

Climate change:

Tackling a global challenge

From COP26 (Glasgow) to COP27 (Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt): What to expect at Africa’s COP

Despite progress towards the shared goal of addressing climate change, COP26 did not sufficiently put the world on track to successfully tackle the problem. The outcomes especially fell short of what Africans had hoped for. On the positive side, the Glasgow Accord kept the “1.5oC warming goal alive,” and countries have been asked to come to COP27, to be held in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt, with more ambitious Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs). A new agreement on global carbon trading was achieved, adding a much-needed tool to the fight against climate change. Negotiators reached other significant agreements in Glasgow, notably 65 countries committed to phasing out coal power, more than 100 countries agreed to slash methane emissions, and 130 countries—representing over 90 percent of the world’s forests—pledged to end deforestation by 2030.

On the other hand, developed countries failed to reach the $100 billion annual funds promised in Paris to developing countries for climate action by 2020. The current NDCs are estimated to reach a warming trajectory of 2.4oC—almost an entire degree above the goal. The discussion on climate “loss and damage”—what damage is caused by climate change and which parties should pay for it—made some modest progress, and the Glasgow Accord called to start a dialogue to discuss funding arrangements. Such an announcement is a major step given that many major powers had previously opposed even using the words “loss and damage” in climate-related negotiations.

“Under the projected warming trajectory of 2.4oC, the impacts of climate change could make many parts of Africa uninhabitable.”

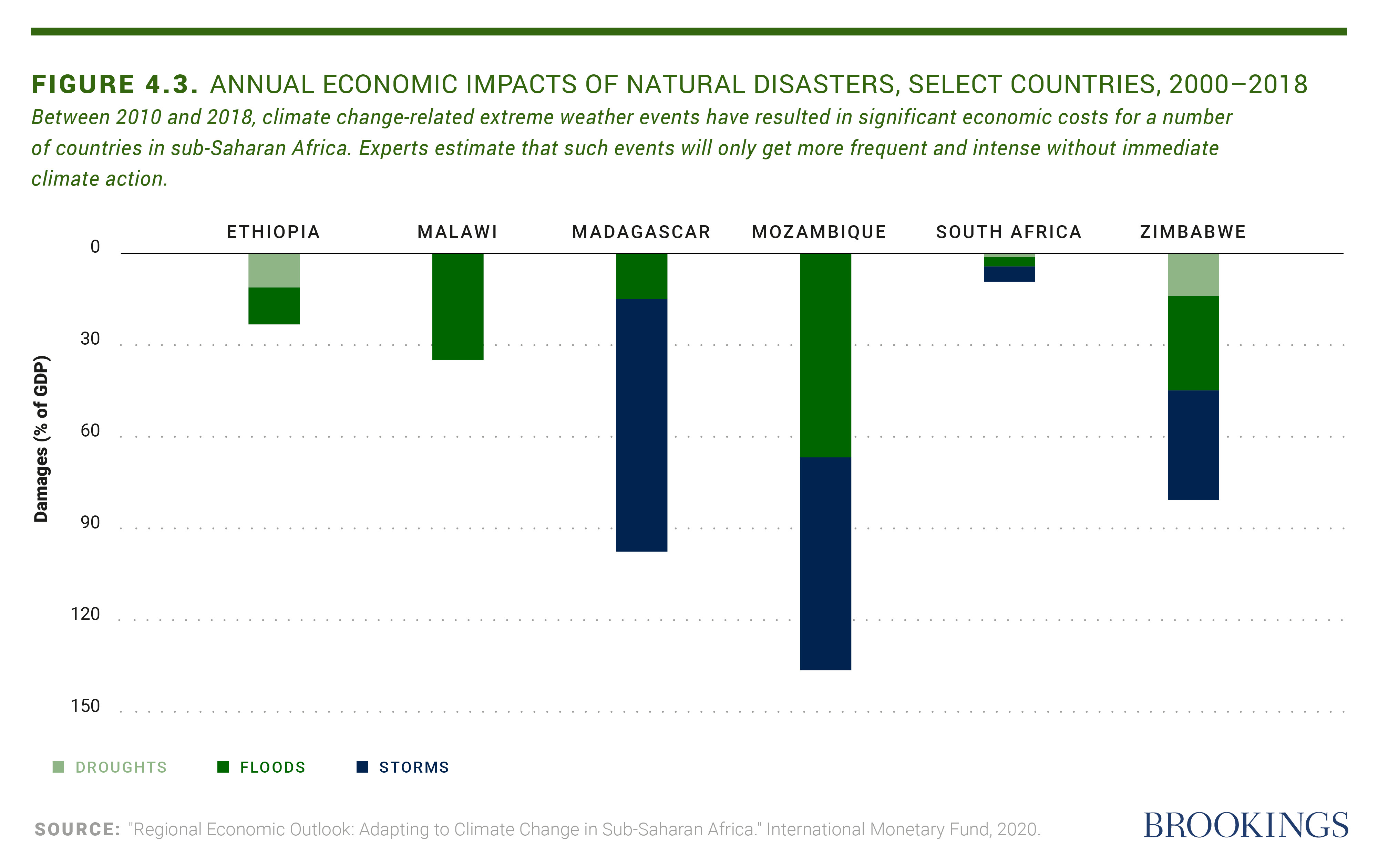

The evident lack of urgency contrasts sharply with the projections from the Sixth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for Africa. Life-threatening temperatures above 40oC are projected to increase by 10 to 140 days a year, depending on the scenario and region. The continent will see drier conditions in most regions, with more droughts but also more flooding. With the rise in sea level (as much as 0.9 meters by 2100 under high-warming scenarios) and more frequent flooding, a current 1-in-100 year flood event will become 1-in-10 or -20 years by 2050, and 1-in-5 years to annually by 2100, even under moderate warming. With rapidly growing cities in low-lying coastal areas in Africa, the damage to property and livelihoods more generally, exacerbated by climate change, will be compounded. In other words, under the projected warming trajectory of 2.4oC, the impacts of climate change could make many parts of Africa uninhabitable. Policy change, financial transfers, and decisive and transformational mitigation measures by the largest-emitting countries are critical. The narrative is clear and remains consistent: Africa’s historical and current emissions of greenhouse gases are minimal; still, the region will suffer some of climate change’s most severe consequences if not adequately addressed.

Even if the world remains under 1.5oC warming, Africa will need to adapt to the new reality of a rapidly changing climate. Thankfully, COP26 did result in some positive steps regarding climate adaptation. The developed world recognized the need to increase funding for adaptation support: The Glasgow Accord “urges developed country Parties to at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing country Parties from 2019 levels by 2025.” Africa was already moving toward a similar goal: The African Development Bank and the Global Center of Adaptation launched a $25 billion program to finance accelerated adaptation in the region earlier in the year.

“Even if the world remains under 1.5oC warming, Africa will need to adapt to the new reality of a rapidly changing climate.”

Africa has great opportunities to help the world fight climate change but cannot do it alone. The protection and sustainable management of its forest and marine resources can provide essential carbon sinks. In fact, the Congo Basin—the world’s second-largest rainforest and which absorbs 1.2 billion tons of CO2 each year —also has vital mineral reserves needed for the clean industries that underpin the net-zero commitments of countries worldwide. The energy, transport, and urban infrastructure that is yet to be built in Africa over the next two decades will either lock the region into a high-emission economic development trajectory or support the global climate goals if adequate additional resources to finance the extra costs of decarbonization are provided at the level and speed needed.

COP27—the “Africa COP”—is a unique opportunity to accelerate progress in climate action and mobilize the partnerships needed for Africa’s rapid, inclusive, green, and resilient development. However, Africa’s policymakers should not be passive recipients of what “others” can do for Africa in COP27. Africans should be well prepared and organized. They should have a unified, active, and consistent voice about the dire consequences of climate change for the continent and the urgency to take action.

“Africa has great opportunities to help the world fight climate change but cannot do it alone.”

First and foremost, the world needs to show at COP27 that progress and firm commitments—not only pledges—are moving the needle towards the 1.5oC warming level. As noted above, Africa absolutely cannot afford a 2.4oC warmer world: At that level of warming, adaptation measures in many parts of the continent may not be technically feasible or financially viable. This point highlights the importance of the other significant opportunity presented by COP27: Leaders must further raise the level of action, speed, and ambition toward climate adaptation, especially for Africa and vulnerable countries in other regions.

As leaders and negotiators descend on Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022, they should focus on four distinct opportunities for decisive, urgent climate action. First, OECD countries and international financial institutions must increase their levels of concessional and private funding for adaptation, including a larger proportion of grants, rapidly and significantly. Second, leaders should increase their focus on the development and scaled-up rollout of adaptation technologies. Climate mitigation technologies receive most of the funding, attention, and support compared to adaptation technologies. At COP27, global leaders must push for a greater balance with adaptation technologies, including the localization and scaling-up of existing African solutions, including multi-hazard early warning systems combining earth observing systems and artificial intelligence with locally trusted communication channels in Africa. Importantly, the scaling up of climate-smart agriculture technologies and practices can tackle the malnutrition and stunting challenge of the region through more productive and resilient food systems. At the same time, climate-smart agricultural technologies can help store carbon in the soil and reduce the pressure on land-use change by improving efficiency and reducing food waste.

“Africa absolutely cannot afford a 2.4oC warmer world: At that level of warming, adaptation measures in many parts of the continent may not be technically feasible or financially viable.”

Third, Africa needs a decisive push to build capacity in climate change action, not only in ministries of the environment but throughout society. The engineers and urban planners need to incorporate climate considerations in designing and constructing Africa’s infrastructure. African farmers need the best data and knowledge to make informed decisions to increase productivity in the face of a rapidly changing climate that is already impacting their crops. Low-income urban households and rural communities need to know what actions to take to better protect their lives and livelihoods against more frequent and intense climate shocks.

Fourth, leaders must pursue the win-win opportunity of rapidly deploying the global carbon market, while helping Africa enter this market, especially with programs that straddle both climate mitigation and adaptation. Nature-based solutions, energy access programs, and blue and green economy platforms can push forward the enhanced resilience of the region while supporting global emission reduction goals.

“The landmark African Continental Free Trade Agreement can provide the foundation for early agreements on free trade of agricultural products that can balance losses caused by climate shocks.”

At the same time, Africa cannot wait. It must use all its tools to mainstream adaptation in its development path. With the pandemic still causing economic and livelihood damages in every corner of the continent, this task will be harder than ever. Still, low-cost, high-return adaptation measures should be prioritized. These range from land use and simple early warning systems to infrastructure maintenance that can reduce flood damage and protection of environmental assets that protect lives and livelihoods. Importantly, the landmark African Continental Free Trade Agreement can provide the foundation for early agreements on free trade of agricultural products that can balance losses caused by climate shocks.

At Sharm el-Sheikh, at the Africa COP, the world must take advantage of the opportunity to fulfill its responsibility together with Africa. A prosperous future of hundreds of millions of Africans will depend on the decisions and actions taken at COP27. A green and resilient path for Africa’s development cannot wait.

Viewpoints

Jeanine Mabunda Lioko offers recommendations for African policymakers looking to balance sustainable development and universal access to electricity.

Amar Bhattacharya reviews financing strategies for Africa to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Freetown Mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr shares examples of how African cities can implement climate change adaptation and mitigation projects.

Amara Nwankpa explores the impacts of the climate crisis on food insecurity in Nigeria and offers a framework for reducing food and nutrition vulnerability while enhancing environmental resilience.

Climate migration—deepening our solutions

Simeon K. Ehui and Kanta Kumari Rigaud underscore the need for bold, transformative, and foresighted action to address climate-related migration in sub-Saharan Africa.

The urgency and benefits of climate adaptation for Africa’s agriculture and food security

Kray, Jenane, Ijjasz-Vasquez, and Saghir estimate the impact of climate change on the future of food security in Africa.