Centering neighborhood priorities for economic inclusion:

Introduction

One year ago, Brookings and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) released a playbook for a new approach to advancing economic inclusion—one that centers disinvested neighborhoods as the locus for achieving inclusive regional economic recovery and growth. Inherently place-based and community-led in nature, this approach—“community-centered economic inclusion”—has been tested by the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, persistent racial injustice, and widening inequities in our nation’s most impoverished communities.

Today, as the economic challenges of the pandemic continue to change shape, muddle the conventions of economic thought, and disproportionately impact people and places that have long been disadvantaged, the value of equity-focused place-based economic development is as important as ever. But so too is understanding the effectiveness of these strategies during a period in which many place-based efforts have had to shift to focus toward meeting basic needs amid prolonged crisis rather than dismantling the long-standing root causes of economic inequity.

This brief presents early outcomes and lessons from five cities that have implemented community-centered economic inclusion for at least one year: Los Angeles, Indianapolis, Detroit, San Diego, and Philadelphia. It provides early insight into the questions: Can cities and regions meaningfully reduce economic inequity by growing more communities of opportunity? How can cities tell if they are on the right track to produce the kind of systems-level change needed to accomplish this? What lessons have emerged for cities looking to reduce economic inequity in today’s pandemic era?

By presenting early outcomes and lessons from the field, this brief seeks to provide guidance for other cities looking to enhance opportunity in their disinvested neighborhoods and test a new kind of economic inclusion rooted in the knowledge, strength, and collective power of community.

What is community-centered economic inclusion and what makes it different?

Disinvested communities in the U.S. have been over-planned and over-studied, often with dismal results to show for it. Despite billions of dollars spent on place-based initiatives, the number of high-poverty neighborhoods in the U.S. has continued to grow at alarming rates over the past four decades.

Some scholars have recently pointed to the flaws inherent in past and current federal place-based programs. For instance, our Brookings colleagues contend that the “what,” “where,” and “who” of most place-based initiatives have gotten it wrong. They argue the “what” is typically too focused on attracting outside investment rather than growing local assets; the “where” is often too expansive or determined by political interests (such as with Opportunity Zones); and the “who” has often failed to prioritize community leadership. Researchers at the Urban Institute have a similar critique, arguing that place-based policies fall short because they rarely center racial equity or systems-level change, fail to truly build community power, and make it procedurally difficult to bridge policy domains and coordinate across agencies—a task that is critical due to the cross-disciplinary nature of place-based challenges.

Given the past and current failures of place-based initiatives—and drawing from four decades of experience in on-the-ground community and economic development in disinvested communities—LISC, in partnership with Brookings, piloted a new place-based approach to economic inclusion: community-centered economic inclusion. The approach, piloted in 2019 in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Indianapolis and codified in our practitioner-oriented playbook, has since been adopted in eight additional cities: Atlanta, Oakland, Calif., Buffalo, N.Y., Detroit, Honolulu, San Diego, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

So, what exactly makes community-centered economic inclusion different? It makes key changes to the “where,” “who,” “why,” “what,” and “how” of previous place-based efforts—seeking to correct for prior downfalls and chart a new approach that centers equity in both process and outcomes.

1. The “where”: While the term “place-based” can apply to areas as small as a district or as large as a region, community-centered economic inclusion operates within “hyperlocal” sub-city geographies that possess a specific set of criteria: 1) the presence of documented economic inequities (e.g., high poverty rates, high unemployment, high housing cost burdens); 2) a concentration of undervalued assets within the neighborhood (e.g., industrial land, anchor institutions, clusters of small businesses); 3) a level of economic activity and population large enough to impact citywide economic outcomes; and 4) the buy-in of neighborhood residents and community-based organizations to lead the community-centered economic inclusion process.

Figure 1: “The Where” in Indianapolis: The Far Eastside

Source: Indianapolis’ Economic Inclusion Agenda for the Far Eastside.

2. The “who”: Past place-based initiatives have varied in the extent to which communities are engaged as partners in the work, with some (such as Empowerment Zones and Strong Cities, Strong Communities) seeking to build local capacity to lead efforts, while others (such as Opportunity Zones) requiring no local connection. By contrast, community-centered economic inclusion relies upon not only the presence of strong community leadership to “backbone” the process, but also requires city and regional stakeholders to align their economic inclusion priorities in partnership with community leaders. The purpose of bringing together these often-siloed groups is to make community-led priorities more achievable (through obtaining the support and resources of city and regional stakeholders), and city and regional efforts more attuned to the realities of disinvested communities.

Leimert Park and the Goodyear Tract in South LA: Two districts included in Los Angeles’ community-centered economic inclusion agendas.

3. The “why”: Place-based initiatives often aim to improve economic conditions in disinvested places without: 1) confronting the root causes of these inequities (many of which stem from policies and practices at the city, regional, state, and federal level); 2) centering racial equity in decisionmaking; or 3) aligning strategies with market realities. Community-centered economic inclusion, on the other hand, takes a structural, racial equity, and market-informed lens to addressing neighborhood disadvantage. It studies the policy drivers underlying current neighborhood conditions, the market failures and strengths impacting communities, and residents’ perspectives on what should be done to address them. In community-centered economic inclusion, understanding the holistic “why” of neighborhood conditions is a necessary prerequisite to determining the “what.”

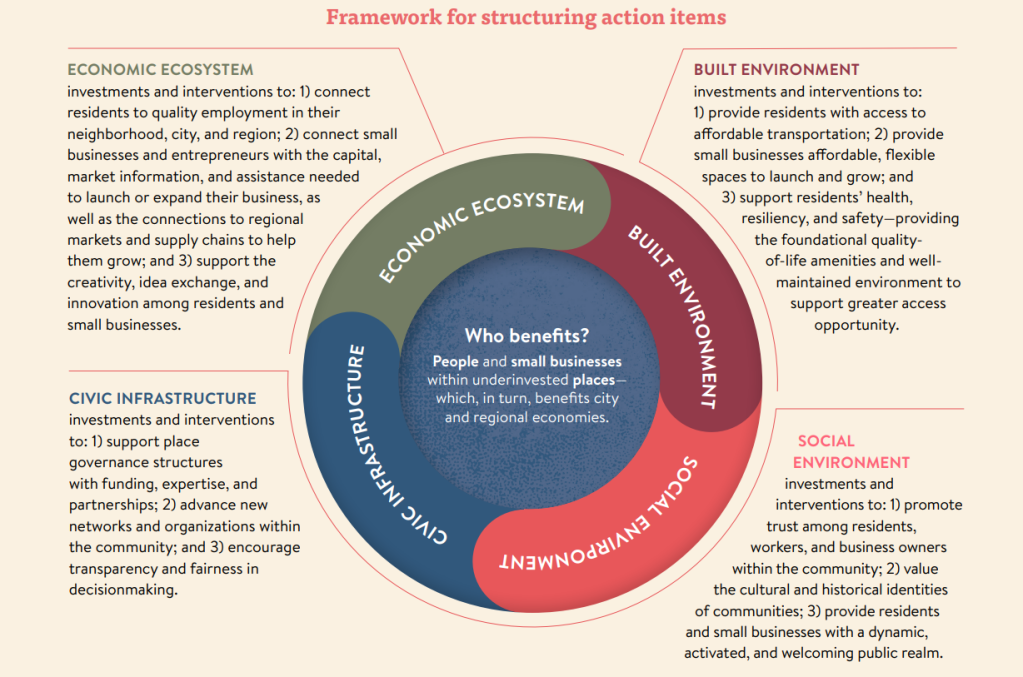

4. The “what”: Most place-based initiatives seek to drive business growth and improve employment outcomes by attracting outside investment into underinvested communities. Community-centered economic inclusion seeks to grow from within by investing in local assets, people, and small businesses to produce broad-based prosperity. It equips local leaders with a four-part integrated framework (see Figure 2) to guide their place-based strategies— encouraging them to not only invest in a place’s economic ecosystem, but also its built environment, social environment, and civic infrastructure.

Figure 2. A holistic framework to structure the “what”

5. The “how”: Although the challenges facing disinvested communities are multifaceted and the solutions cross-disciplinary, many place-based initiatives struggle to bridge policy domains during implementation. Often, this is because they are housed within a single agency with its own mandate, making it difficult to work across governmental departments with different goals. Community-centered economic inclusion is not a government-led initiative; it originates in and is led by community-based organizations and residents, in collaboration with government officials and other stakeholders. The process of convening the “who” in community-centered economic inclusion inherently sets communities up for cross-sectoral collaboration during the “how”—as the community-based organizations, residents, city agencies, citywide employers, and regional actors that developed the community-centered economic inclusion strategies are ultimately tasked with co-owning implementation, outcome-tracking, and sustainability.

In short, community-centered economic inclusion is a place-based approach that values process as well as outcomes in achieving equity—seeking to build community power, shift relational dynamics, and bridge policy siloes, all while working toward equity-focused neighborhood-level change. Rather than expecting economic development investments at the city and regional level to “trickle down” to disinvested neighborhoods (which they rarely do), it contends that by improving economic outcomes in underinvested places, these positive outcomes will “trickle up” to strengthen the city and region at large.

Tracking outcomes for inclusive economic development

Often, place-based initiatives are funded and implemented without the time or resources to track who benefits and how they benefit over time. This can contribute not only to a poor understanding of results, but can also exacerbate community distrust. To be truly accountable to the communities they purport to serve, place-based initiatives must have clear visions of success and shared mechanisms for tracking progress toward short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes. To this end, this brief tracks early outcomes from the first year of community-centered economic inclusion in five cities—capturing successes, challenges, and lessons from early implementation efforts across different market contexts. It does so using qualitative interviews with key implementation stakeholders, as well as a thorough review of local sites’ individual year-one metrics.

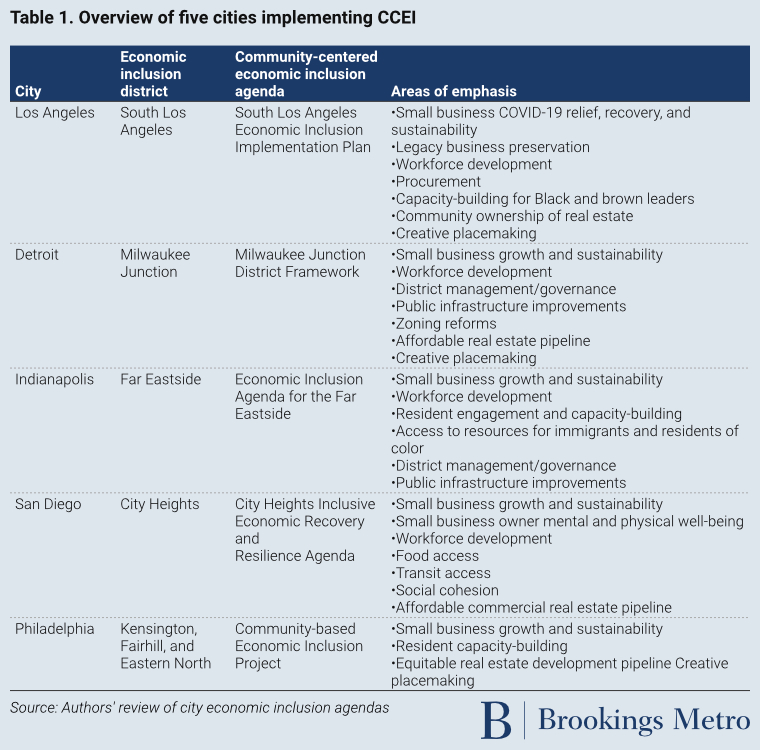

To frame our discussion of early outcomes, it is important to first define the long-term vision of success for community-centered economic inclusion, the framework for translating that vision into action, and the outcomes that can gauge progress toward this vision. In the case of community-centered economic inclusion, the long-term vision is to support more equitable cities and regions where everyone—regardless of race, ZIP code, or income—can live in communities of opportunity where they have access to employment, housing, fresh food, green space, and transportation. The framework for achieving that vision is codified in each city’s respective economic inclusion agenda (see Table 1), and the outcomes to gauge progress are discussed throughout this brief.

Philadelphia’s community-centered economic inclusion district.

Findings from the first year of community-centered economic inclusion

Three early outcomes emerged from the first year of community-centered economic inclusion implementation across the five cities.

Finding #1: Community-centered economic inclusion strengthened the capacity of small and grassroots community-based organizations to advance community priorities.

In disinvested communities nationwide, community-based organizations provide the critical infrastructure to meet residents’ needs when other systems have failed to champion community-led economic and community development initiatives. These organizations respond to a diverse array of community priorities, including developing affordable housing, providing loan capital and technical assistance to small businesses, offering social services to residents in need, implementing job training programs, and advocating for broader policies that support disinvested communities. Yet the reach and scale of many community-based organizations are not sufficient to address the challenges of economic exclusion in communities. In places where an established network of community-based organizations does exist, these organizations often lack the funding and staff to sustain their current programs—let alone start new initiatives aimed at dismantling the root causes of economic exclusion. In other neighborhoods, no network of established community-based organizations exists, meaning residents are left without access to the critical civic infrastructure needed to realize their priorities.

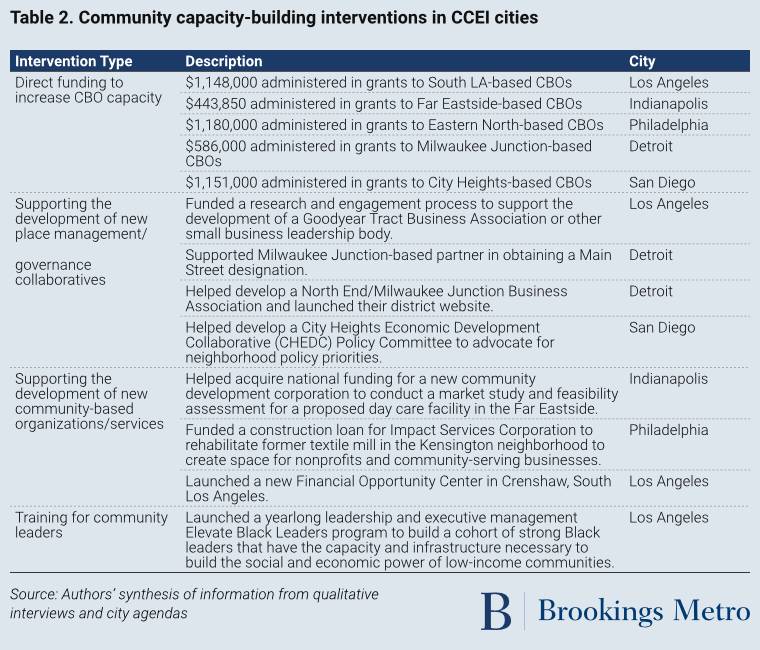

To address these capacity gaps, a long-term goal of community-centered economic inclusion is to build and scale robust networks of locally led and controlled community-based organizations and governance structures in underinvested neighborhoods. So far, the five study communities have made significant progress toward this goal by: 1) providing direct funding to smaller and more grassroots community-based organizations to scale their efforts that previously lacked capacity; 2) strengthening the place governance ecosystem in the neighborhood; 3) launching new neighborhood-based organizations; and 4) providing training to directly support Black leadership in the community development space (see Table 2 for examples).

Small businesses served as part of San Diego’s City Heights relief funds.

Across cities, qualitative interviews revealed that one of the most impactful supports community-centered economic inclusion provided was to “allocate more resources to what [grassroots organizations] already do.” As one South LA-based community organization leader told us, “When I read [the South LA Economic Inclusion Agenda], it was a continuation of our work. It just increased why we needed to be part of it. We want to be part of it so development is done right, so it’s done under community ownership and community control.” This funding of communities’ existing priorities was intentional, as all five agendas aimed to scale and sufficiently resource the ongoing efforts of locally controlled organizations. For instance, LISC Los Angeles has provided South LA community-based organizations with over $1 million so far to implement their priorities, including supporting street vendor campaigns, helping youth identify careers in the community development industry, retaining legacy businesses, and strategically acquiring commercial real estate for community ownership.

In addition to scaling existing community efforts, community-centered economic inclusion increased community capacity by supporting the development of new community-based institutions and governance structures. In Detroit, for instance, LISC leveraged the community-centered economic inclusion process to help a community-based partner, Vanguard Community Development Corporation, receive designation as a Michigan Main Street program to focus on revitalization strategies to attract new residents, business investments, economic growth, and job creation to their central business districts and launch a new North End/Milwaukee Junction business association. In San Diego, LISC helped develop a City Heights Economic Development Collaborative (CHEDC) Policy Committee to advocate for neighborhood policy priorities, such as decriminalization of street vending and permitting for “micro-enterprise home kitchen operations.” In both Los Angeles and Indianapolis, LISC contributed to the development of new community institutions, including a Financial Opportunity Center and day care.

Finally, in the first year, community-centered economic inclusion helped cities build the capacity of not only community institutions and governance structures, but also of community leaders. LISC Los Angeles, for instance, created an Elevate Black Leaders program to support Black-led organizations and leaders in obtaining the capacity and infrastructure to build social and economic power in their communities. Taken together, these efforts—while still early—are laying the groundwork for strengthening and scaling neighborhood capacity and ensuring that the “who” leading and implementing community-centered economic inclusion is truly the community.

Finding #2: Community-centered economic inclusion shifted relationships between underinvested communities, their city, and their region to better connect neighborhoods to opportunity.

Economic conditions in underinvested neighborhoods did not occur by accident. Rather, they were produced by a long history of local, state, and federal policies that segregated neighborhoods and starved them of the resources and opportunities needed to thrive. Today, however, city and regional economic development policy is largely agnostic to place—meaning it does not typically focus on improving outcomes for disinvested neighborhoods. When city and regional efforts do focus on disinvested neighborhoods, these efforts are often triggered by government programs (e.g., Enterprise Zones, Opportunity Zones), or by private firms, anchor institutions, and other organizations looking for a development site. Such efforts have a track record of failing to benefit existing residents or small businesses—particularly residents of color and BIPOC-owned small businesses—contributing to further distrust between underinvested communities and city and regional institutions.

For these reasons, a long-term goal of community-centered economic inclusion is to reorient city and regional economic development policy to more proactively and equitably prioritize “place”—and to do so in genuine partnership with community leaders in disinvested neighborhoods. In the first year of implementation, the five cities made progress toward this goal by: 1) facilitating relationships between smaller community-based organizations and city officials; 2) strengthening connections between community-based organizations to present a united platform on neighborhood policy priorities; and 3) encouraging the city to prioritize inclusion districts in citywide economic development decisionmaking.

In the first year, cities accomplished a critical first step in facilitating connections and building relationships between community-based organizations and city stakeholders. In the Far Eastside of Indianapolis, for instance, the community-centered economic inclusion process was the first time that many city officials had been involved in focus groups to hear the perspectives of residents and community-based organizations. As one Far Eastside resident and organizer told us when reflecting on the process, “[The city] sees us now. I just don’t think we were seen before…With this process and the developments since, it gave the city the opportunity to get all the grassroots organizations together that work collectively and have been for a long time.” Over time, these connections also led the city to seek out community-based organizations they met through the process for different reasons. For instance, as one South LA-based community stakeholder told us, “I personally didn’t feel like I had the most robust relationship with [the councilmember’s office]. As a result of [the South LA Economic Inclusion Agenda] and our partnerships made through it, they see us in a different light. They see us as partners and want to talk to us about other things.”

A critical driver behind the improved relationships between the city and community was improved coordination between community-based organizations within underinvested neighborhoods. As an inherently collective and community-led effort, community-centered economic inclusion funds local organizations to co-develop and co-implement strategies together. As one community stakeholder told us, “Having an initiative like this cements relationships. Programs like this give a reason for people to work together—they make connections happen physically, mentally, and programmatically.” By allocating funding for collaboration (which can often be difficult to obtain), community-centered economic inclusion helped strengthen neighborhood partnerships to present a united front and policy agenda for community priorities.

Most impactfully, the community-centered economic inclusion process began to influence city policy and practice toward disinvested neighborhoods. In Indianapolis and Los Angeles, for instance, neighborhood agendas provided a framework for the city to better fund and respond to neighborhood priorities. In Indianapolis, the Far Eastside neighborhood was selected for the Department of Metropolitan Development’s (DMD) 2021 Lift Indy grant, which provided $3.5 million in Department of Housing and Urban Development funding to achieve community and economic development goals embedded in neighborhood plans. As one community leader told us, “Because we did have [the Economic Inclusion Agenda for the Far Eastside plan] written, when we applied for the Lift Indy grant, we were selected…I don’t know if we would have been selected had the agenda not happened.” A DMD representative echoed this sentiment: “We want to make sure that when we go into these neighborhoods, we’re invited and there’s a neighborhood plan in place…LISC has done a good job of laying that foundation.”

In Los Angeles, LISC was able to use the community-centered economic inclusion process to better coordinate and maximize the benefits of the city’s new JEDI Zone program (which offers city incentives to small businesses looking to expand their footprint) to benefit businesses in South LA. As one LISC stakeholder told us, “We’ve been able to use the plan to build a better relationship with [the city] and for them to think of LISC and this process as an asset. For instance, with the JEDI Zone—without this plan we would have never been in conversations with them about that.”

While there is a long way to go to reorient city policy and practice to respond to the needs and priorities of disinvested neighborhoods, the relationships and connections established during this first year have laid critical groundwork for these neighborhoods to be seen, heard, and listened to.

Finding #3: Community-centered economic inclusion delivered early wins in increasing capital investment and training in underinvested neighborhoods, particularly for the under-resourced, minority-owned small businesses located within them.

Minority-owned businesses—particularly Black-owned businesses— are at a systematic disadvantage for business development and growth, as they have been denied equal opportunities for wealth accumulation and systematically devalued in the marketplace. COVID-19 magnified these injustices, as minority-owned businesses and businesses in majority-minority neighborhoods had unequal access to federal relief, resulting in disproportionate closures. In the first year of implementation, community-centered economic inclusion made progress in combatting these challenges by: 1) providing direct capital to under-resourced neighborhood small businesses that otherwise face barriers in obtaining relief; and 2) providing targeted technical assistance for neighborhood businesses aimed at retaining legacy businesses, expanding digital skills, and supporting Black and Latino or Hispanic entrepreneurs.

As Table 3 demonstrates, cities delivered significant capital investment to under-resourced small businesses in their first year. Los Angeles, for instance, delivered over $5 million in grants to Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned small businesses, while San Diego administered nearly $1 million. These cities were able to deploy this capital to many hard-to-reach businesses; as one Los Angeles stakeholder told us, “I take it as a very large victory that the majority of the loan applicants had never received capital before. We were successful in reaching the most marginalized business owners. It was not easy—there’s a lot of mistrust. We had to do on-the-ground canvassing and work with partners to gain that trust. With the applicants that we received, they’re now more engaged in some of our other programs.” Even cities with relatively smaller grants were able to make an impact in supporting small businesses and building trust. As one Far Eastside-based stakeholder told us, “Being able to invest that kind of grant funding was important for the neighborhood to feel seen, heard, and known—for the funders, for everyone involved, to bring awareness to the volume of businesses there.”

Outside of direct capital investment, the five cities also implemented new training programs and services to help small businesses grow and reach new markets (Table 4). Los Angeles, for instance, provided 288 South LA minority-owned businesses with technical assistance, including launching new initiatives to support legacy businesses and Black businesses in the personal care and retail space. Indianapolis, too, developed culturally responsive small business technical assistance, partnering with the Indy Black Chamber of Commerce and Indy Chamber’s Hispanic Business Council to offer classes specifically for Black and Latino or Hispanic entrepreneurs. San Diego adopted a holistic approach to supporting small businesses—investing not only in training for vulnerable groups, but also in free counseling and mental health services for small businesses and their employees in City Heights. All of these efforts are working toward fostering local ecosystems where minority-owned businesses are connected, expanding, and thriving.

While the bulk of cities’ capital investments in the first year supported small businesses and community-based organizations in underinvested neighborhoods, some cities made strides in advancing the more holistic kinds of investments community-centered economic inclusion calls for. Table 5 provides examples of these kinds of efforts, ranging from homeownership programs to urban farm hubs to mental and physical health programming.

While the kind of neighborhood-level change that community-centered economic inclusion seeks to accomplish will take years—if not decades—to achieve, understanding these early outcomes is an important step in ensuring accountability and long-term success.

Murals painted for Detroit’s community-based partner, Vanguard CDC.

Lessons for future adoption

Just as important as capturing early outcomes is acknowledging where the five cities could have improved. Five key lessons emerged from the first year of implementation—organized by the five distinctive elements of community-centered economic inclusion—that can help other cities better achieve the long-term goals of community-centered economic inclusion.

- The “where”: Select places where a credible community partner is on board to co-own the process and leverage resident relationships to support it, or devote additional resources to building this partnership prior to starting. Community-centered economic inclusion aims to increase capacity in underinvested communities, but also requires a certain level of community capacity from the outset to be successful (e.g., a credible place-based partner to co-own the process). In Detroit, San Diego, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles, for instance, LISC offices chose neighborhoods where they had long-standing relationships with at least one community partner who had residents’ trust and an established track record of engaging them. As one Detroit stakeholder told us, “Resident engagement is [our community partner’s] bread and butter. They did the organizing. They led the community engagement sessions using the channels they already have developed.” Similarly, San Diego worked with community-based partners to set up over 50 one-on-one interviews with residents identified as “most vulnerable to exclusion,” to ensure their perspectives were heard and incorporated in the plan. Other cities, like Indianapolis, selected a neighborhood without first establishing a core place-based partner, meaning they had to devote significant time and resources to overcoming trust barriers with residents and grassroots organizations before getting started on the process. As one Far Eastside stakeholder told us, “From the standpoint of discussion with residents, their concerns were around quality of life, not economic development…Residents were like, ‘We need a grocery store and better housing, we need that first before you can attract businesses.’ There was significant pushback from residents that made it challenging.” A key lesson from these different experiences is to either: 1) select places that not only fit the criteria for community-centered economic inclusion, but that also have community partners on board with existing resident relationships; or 2) build in additional “pre-planning” time and resources to facilitate those relationships prior to beginning community-centered economic inclusion.

- The “who”: It is not enough to convene cross-sectoral stakeholders at the same table; they must also clearly understand their roles as co-owners and co-implementors. All five cities were successful in convening community, city, and regional stakeholders to co-develop priorities for community-centered economic inclusion. Where some cities fell behind, however, was in clearly communicating to these stakeholders—particularly city and regional actors—that they also need to collectively implement strategies to achieve these priorities. The cities that are farthest along in implementation devised strategies to make roles, expectations, and financial resources clear from the outset. As one LISC Los Angeles stakeholder told us, “Be clear with the Advisory Committee by saying, ‘We want you to be implementors—picture yourself in this plan and this is the money we have for you to execute it.’” In San Diego, LISC asked their group of cross-sectoral stakeholders to respond to a “call for ideas” that corresponded with the goals of the plan; then, stakeholders proposed projects they wanted to work on that met the goals of the plan. LISC then made implementation grants based on the ideas from partners. Regardless of the strategy, it is essential to be clear from the outset that community-centered economic inclusion doesn’t just require the feedback of cross-sectoral stakeholders—it also requires a sustained commitment to contribute to implementation.

- The “why”: Before deciding on the specifics of the “what,” develop a shared vision of success that can collectively be defined, understood, and measured across organizations. A central tenet of community-centered economic inclusion is to understand the systemic, structural, and market-based failures impacting disinvested communities and devise a shared vision for correcting them. Prior to implementation, all five cities successfully defined the injustices impacting their neighborhoods and specific strategies to alleviate them. However, some failed to articulate a longer-term vision. As one stakeholder told us, “We’re hitting all of our outcomes that we told the funders. But we never really laid out long-term goals, we don’t have a guiding North Star of what the large-term ‘goal’ is.” To truly develop equity-focused strategies, indicators, and outcomes that are not only useful for funders but can also be used to hold the effort as a whole accountable, implementors must agree upon a long-term vision of success from the outset and devise their strategies based on achieving that vision. See the discussion in Section 3, “Tracking outcomes for inclusive economic development,” for further guidance.

- The “what”: Widely disseminate and communicate community-centered economic inclusion agendas to ensure accountability and adoption. While community, city, and regional partners in all five cities were actively working toward implementing aspects of their agendas—and in some cases, were implementing strategies for every aspect of the agenda—residents, small businesses, and some community-based organizations weren’t always aware that strategies were aligned as part of a larger vision or initiative. As one Los Angeles stakeholder told us, “[Small businesses] are not reading this strategy and thinking it’s a thing for them. They think that what they’re getting is from a city program or a county program.” Another Indianapolis implementation partner told us, “I’m not aware of what other organizations and peer groups are working on for the agenda,” adding that more transparency would have been helpful for remaining accountable to the people the agenda is meant to serve. In Philadelphia and San Diego, however, stakeholders used the community-centered economic inclusion process to widely disseminate a shared vision for their neighborhoods. As a LISC Philadelphia stakeholder told us, “A public rollout of a shared playbook or mission statement was a necessary step for building relationships with public officials for the objectives we’re trying to change.” In San Diego, LISC conducted individual follow-ups with all organizations and residents engaged during the planning process to tell them when they were implementing a program that came from their input. As one San Diego stakeholder told us, “Everyone who had any role in shaping the agenda—all those folks surveyed and interviewed—we shared it with them. As we did different pieces of implementation, we’ve emailed them and showed them how what they said is actually manifesting in the neighborhood.” Regardless of the mechanism, publicly disseminating the “what” and progress made on achieving it is critical for community accountability.

- The “how”: Raise a sufficient amount of implementation funding prior to agenda completion to deliver early wins, while continuing to use the agenda to acquire additional resources during implementation. The scale of funding required to achieve and sustain intended outcomes will vary across cities, but one clear lesson emerged from the five cities: Cities should raise enough resources prior to implementation to provide grants to partners to implement key strategies and deliver early wins for residents. As one San Diego stakeholder told us, “The extent to which you can have implementation dollars—at least some—that you can point to and say to partners, ‘As soon as this plan is done, we’re going to make these grants,’ is important. Even if you just have some funds, tell people that implementation is imminent, and the plan won’t be sitting on shelf. Especially in places like City Heights where there’s been a ton of planning processes and nothing comes of them.” The five cities varied considerably in the resources they had available for the first year of implementation, with some raising over $3 million from a variety of local and national sources and others working with a couple hundred thousand dollars from purely local sources. But the most important factor in building trust and buy-in was ensuring these resources were leveraged early and with transparency to generate excitement amongst community-based implementors and residents.

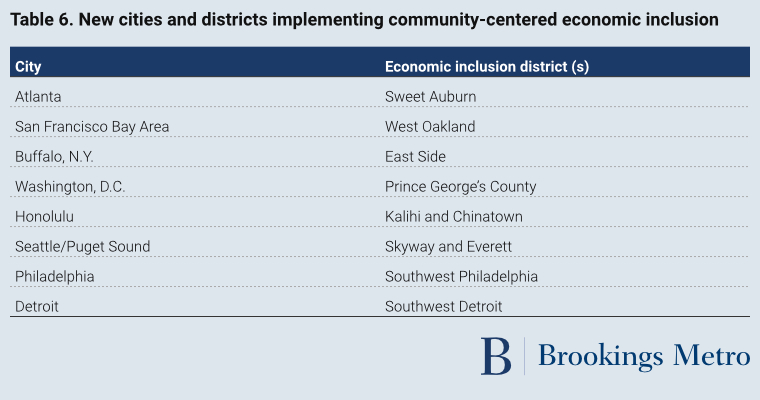

Since being adopted in Los Angeles, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, San Diego, and Detroit, community-centered economic inclusion has scaled to six new cities and two new neighborhoods within existing cities (see Table 6). To some extent, this is a “win” in itself, as community-centered economic inclusion is encouraging more cities and regions to adopt equity- and place-focused economic development policies that invest in growing more communities of opportunity to benefit more people. However, it is critical to be mindful of the above-mentioned lessons to ensure that such efforts are truly responsive and accountable to the communities they are designed to serve.

Conclusion

Place-based initiatives take years, if not decades, to transform systemically disinvested communities into communities of opportunity where residents can access upward mobility and generational wealth. While community-centered economic inclusion is too new to track progress toward these critical aims, the approach is garnering significant successes in shifting resource flows, capacity levels, and power dynamics within underinvested communities.

At its core, community-centered economic inclusion provides cities not only with a community-led agenda for investing in underinvested neighborhoods, but also with an entirely new way of allocating resources, crafting policy about place, and building partnerships with residents who have too long been excluded. It is these “softer,” harder-to-measure outcomes—the relationships built, reorientation of city decisionmaking, and shifted balance of power—that will have lasting value and provide the foundation to achieve larger-scale neighborhood change in the years to come.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the stakeholders that participated in interviews to inform this brief. They also thank Jennifer S. Vey, William Taft, Elizabeth Demetriou, Miranda Rodriguez, Deborah Membreno, Emily Scott, Rachael Viscidy, Jackie Burau, and Avital Aboody for their review of various drafts of the brief. Any errors that remain are solely the responsibility of the authors.