Beyond traditional measures: Examining the holistic impacts of public space investments in three cities

Editor’s note: This brief is part of a three-part series which examines the economic, social, and civic impacts of public space investments in Albuquerque, N.M., Buffalo, N.Y., and Flint, Mich.

Public spaces have long been shown to enhance community well-being—producing positive health, environmental, economic, and social outcomes for residents who can access them.[i] The COVID-19 pandemic made these benefits increasingly obvious, as public spaces provided critical places for people to gather and access social services, served as refuges for small businesses to safely operate, and even helped reduce racial disparities in COVID-19 infection rates.

But the positive outcomes associated with public spaces are not evenly distributed. A robust body of research demonstrates that within cities, people of color and low-income residents are more likely to live in neighborhoods with fewer public spaces or with public spaces that are small, poorly maintained, lack programming, or have limited play options.[ii] Even in neighborhoods that do have quality public spaces, their benefits may still be unevenly distributed, as many of the traditional economic outcomes correlated with public space investments (such as higher land and property values) may fail to serve low-income residents and businesses, particularly those renting and leasing. In “hot market” neighborhoods, such outcomes may even fuel displacement.[iii]

Given these issues of access and equity, there is growing recognition among public, private, and civic sector leaders that it is necessary to look beyond traditional indicators of economic value and neighborhood-level change to examine: 1) who is benefiting from the value that public spaces produce; 2) how such benefits are allocated across residents of different races, incomes, ability statuses, and tenures in a community; 3) whether public spaces produce additional benefits that traditional measures are not capturing; and 4) how to harness the power of public space investments to benefit more people in more places.

Some of these questions can be answered using equity-focused metrics, yet numbers alone cannot tell the whole story. They particularly fall short in revealing what residents, small businesses, and other community-based stakeholders perceive the value of public space investments to be and who stands to gain the most from such value.

This research series seeks to fill that gap using in-depth, on-the ground research in Flint, Mich., Albuquerque, N.M., and Buffalo, N.Y.—examining the holistic impacts of public space investments that numbers alone cannot capture. Centering the voices of residents, small business owners, and other community-based stakeholders, this series looks at the impact of public space investments on places’:

- Economic ecosystems: Exploring the role that public spaces can play in supporting locally owned small businesses, connecting underserved residents to entrepreneurship and other opportunities, and strengthening communities’ local assets.

- Social environments: Analyzing the ways that public spaces can either bridge or exacerbate social divides, promote social cohesion, and reflect the culture and history of communities.

- Civic Infrastructure: Examining how the place governance entities that steward public spaces can leverage their roles to enhance the capacity of other local organizations, offer community-centered programming, and nurture public spaces as hubs for civic engagement.

This introductory brief provides a short overview of the purpose of the series and the public space investments we studied. The other three briefs in the series present the evidence base on public spaces’ economic, social, and civic outcomes, our research methodology, and an overview of our findings.

Defining “public space”

Although public spaces are commonly conceived of as parks or other green spaces, this series defines public spaces as those spaces in which people take part in public life—including parks, plazas, streetscapes, waterfronts, other permanent cultural assets such as museums or historical sites, as well as publicly accessible socioeconomic assets such as farmers’ markets, “streeteries,” and pop-up cafes.[iv] This series posits that public spaces are inherently interconnected with their surrounding neighborhoods—impacting the people and small businesses beyond immediate park boundaries and impacted in turn by broader issues of power and access that determine who is able to use and benefit from a public space.[v]

Examining downtown public space investments in Albuquerque, Buffalo, and Flint

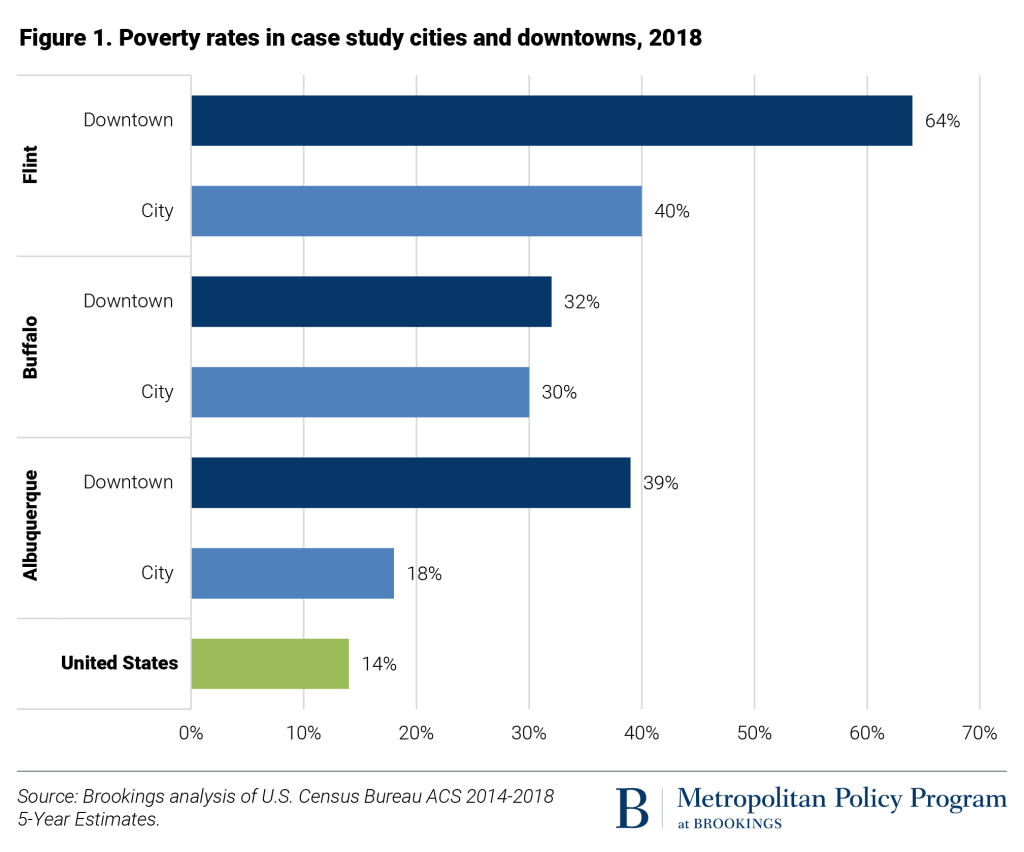

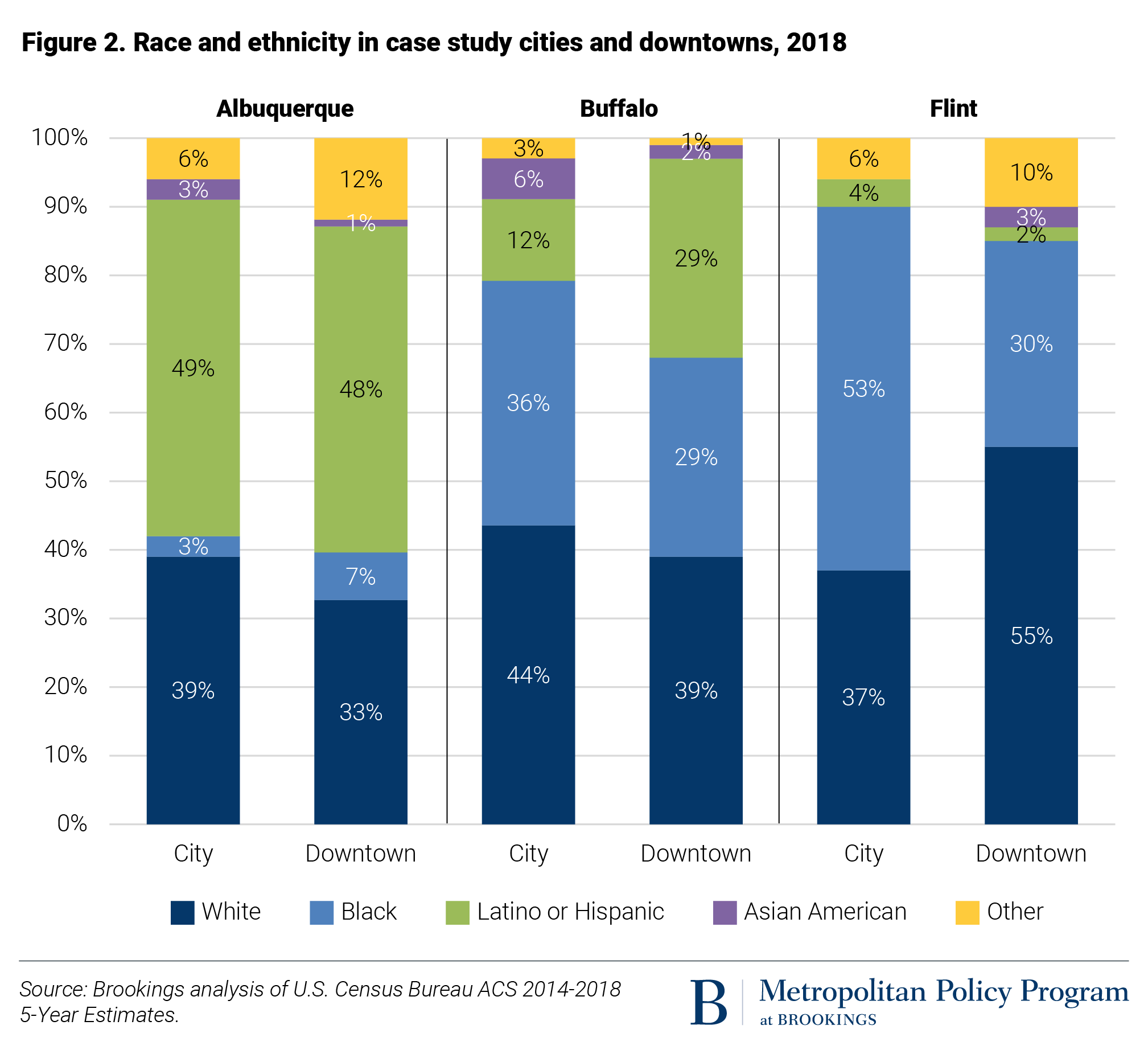

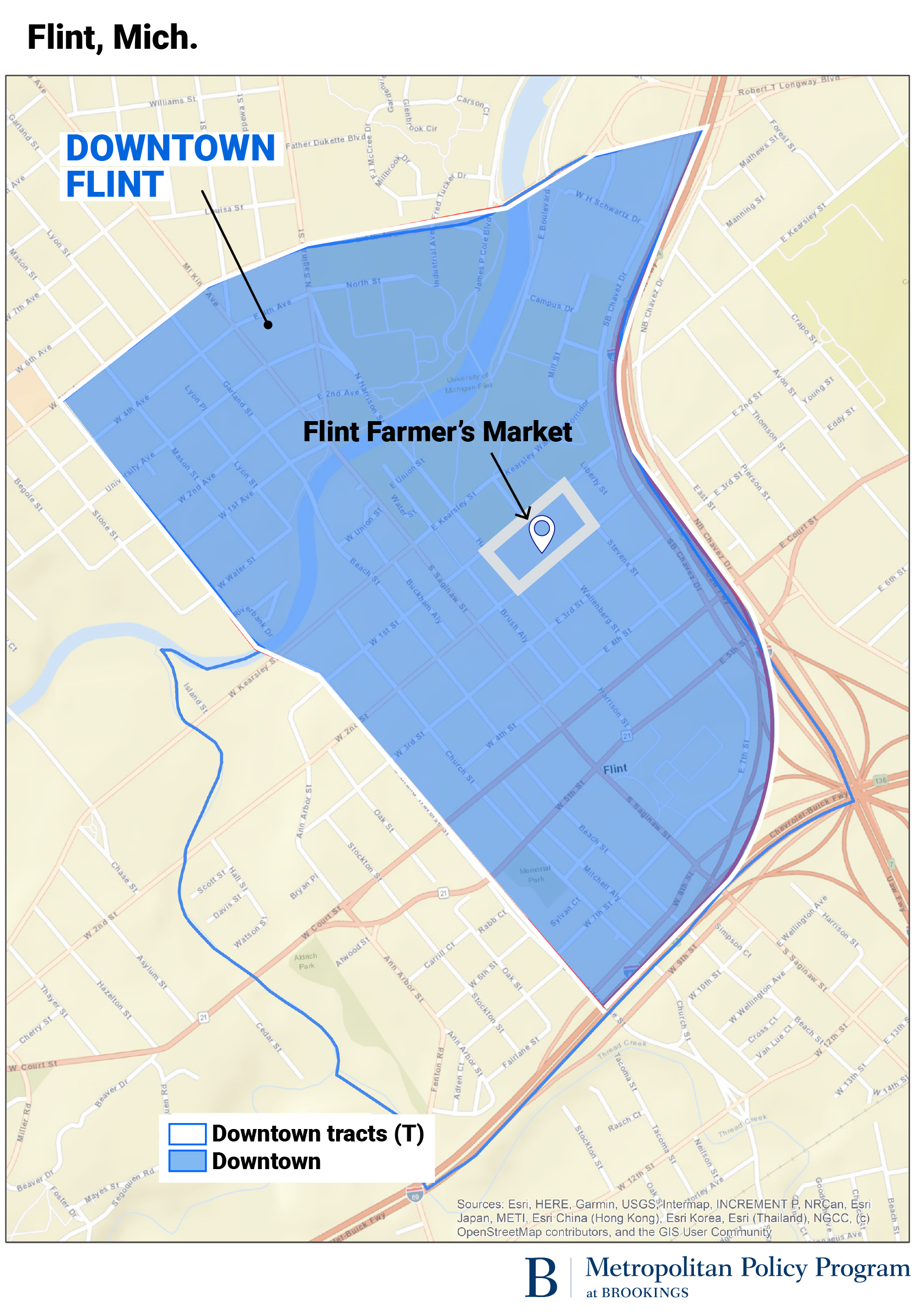

This series examines downtown public space investments in Albuquerque, Buffalo, and Flint—three cities that have long experienced social and economic divides. Each city has higher poverty rates than the country as a whole, lower-performing downtowns compared to nationwide trends, downtown populations with higher poverty rates than the city at large (Figure 1), and a significant population of residents of color citywide and living downtown (Figure 2).

To better gauge the relationship between public space and community well-being, we selected public space investments with the stated goals of spurring revitalization and growth in the downtown area. This site selection enabled us to not only qualitatively examine the role of public spaces in revitalization, but also to begin to understand whether any purported revitalization was reaching all residents, particularly those that are underserved. This is important for public space investments downtown—the stated goals for which often include driving economic vitality for the city as a whole—but which can also raise thorny equity issues about which parts of town are “worthy” of investment and which neighborhoods remain neglected.

The three public spaces we studied (presented below) each has its own unique history, but all had recently undergone placemaking efforts to strengthen their impact on economic growth.

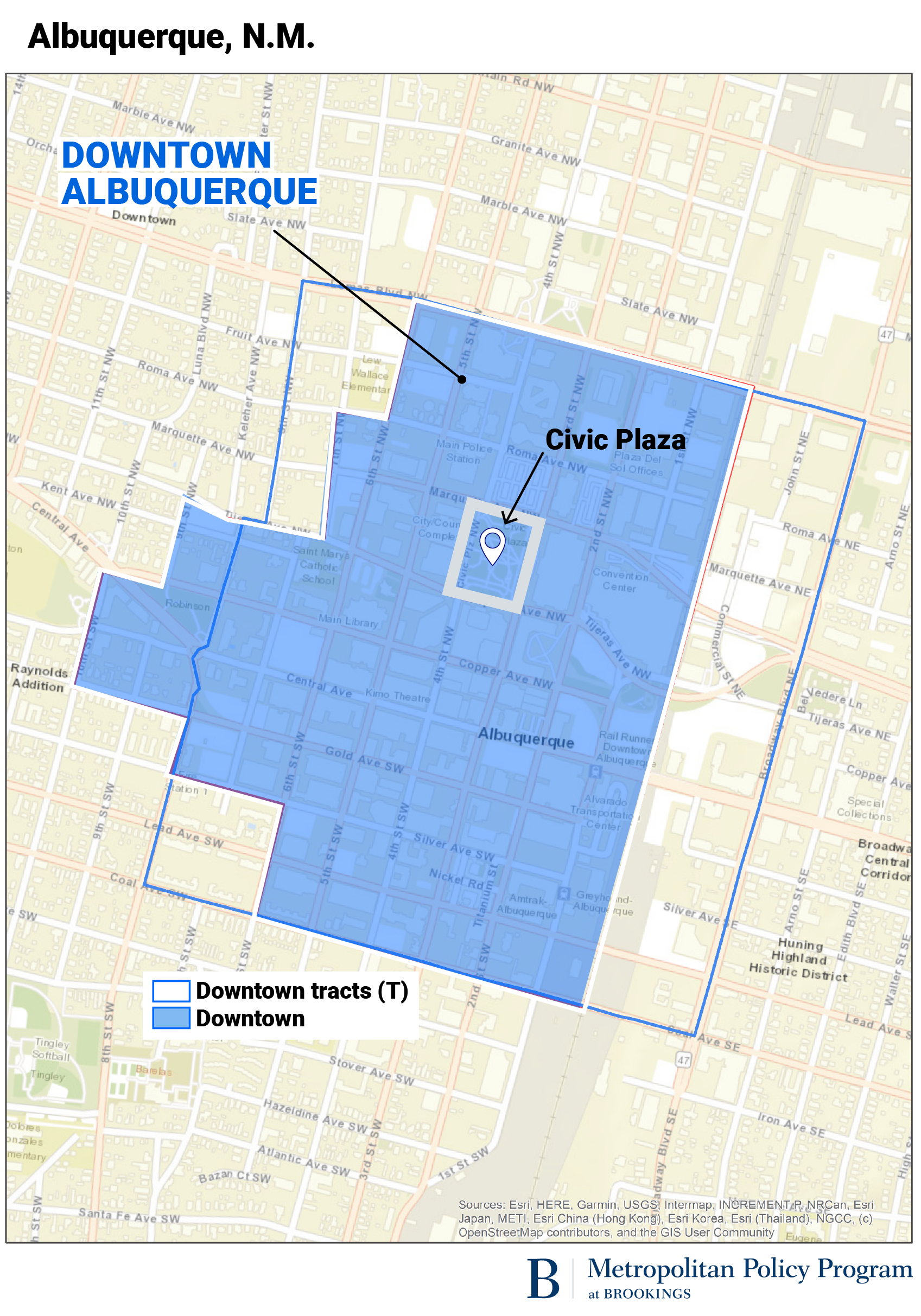

Civic Plaza, Albuquerque: Civic Plaza is a large public plaza (capacity of 20,000 people), adjacent to downtown Albuquerque’s Convention Center and city government offices. It was created in 1974 to host large outdoor events and was managed by the city until 2015, when DowntownABQ MainStreet applied for a placemaking grant and worked with Project for Public Spaces to implement “lighter, quicker, cheaper” improvements to make the space a more welcoming hub for events and community gathering. After that, the Convention Center entered into an agreement with the city to manage and activate the plaza. The city has since funded additional improvements in the space—including a new fountain and play space for children—with the larger goal of transforming the Plaza into a community-oriented gathering space and hub for downtown activity.

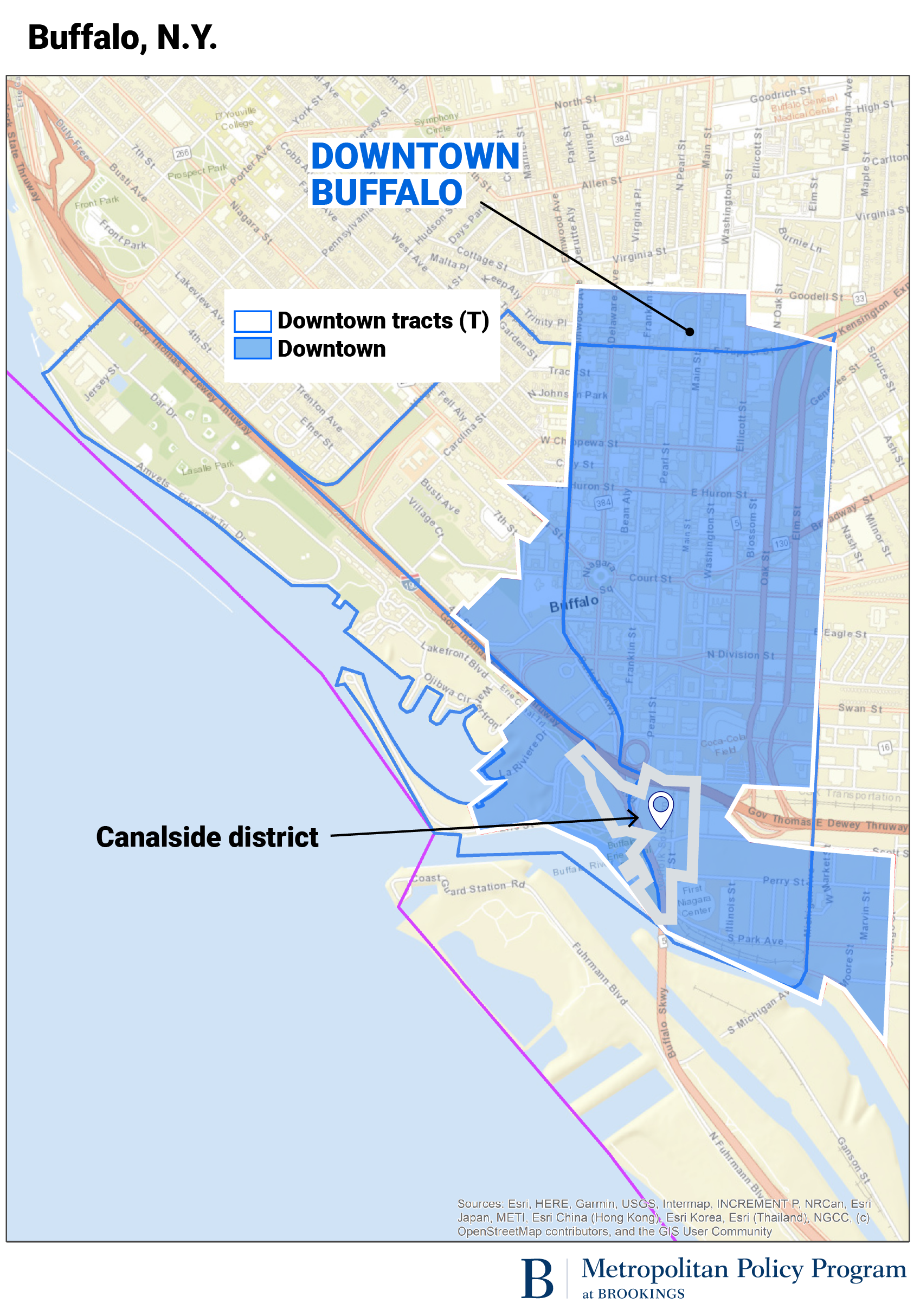

Canalside, Buffalo: Canalside is at the center of revitalization efforts to turn Buffalo’s postindustrial waterfront into a mixed-use development and entertainment destination. Over the past 11 years, the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation (ECHDC), a subsidiary of New York State’s Empire State Development, has been working to revitalize the space to include new waterfront access, private development, and programs and activities. Originally, the big-box retailer Bass Pro Shops was going to be the redevelopment anchor, but Buffalo residents pushed back with a public uproar, resulting in the company stepping away from the site. In 2011, ECHDC went back to the drawing board, worked with Project for Public Spaces for community visioning strategies, and developed a new master plan for a mixed-use urban entertainment hub. Canalside is in the middle of this development plan, and ECHDC has since acquired the Outer Harbor (more than 200 acres of green space). The waterfront is part of the central downtown business district and is in the process of developing its own identity as a neighborhood, although there is a still a long way to go.

Flint Farmers’ Market, Flint: The Flint Farmers’ Market is an over 100-year-old community institution in Flint. In 2011, the market outgrew its longtime location along the Flint River and moved into a former newspaper printing plant in the heart of downtown. This move was spearheaded by the Uptown Reinvestment Corporation in collaboration with the Mott Foundation, and is part of a larger revitalization strategy to create a Health and Wellness District downtown. The district has attracted $36 million in new investment from, among others, Michigan State University and the Genesys Health System (both located in the district), and stakeholders coordinated to co-locate Hurley Children’s Clinic on the second floor of the Farmers’ Market. In 2011, market leadership worked with Project for Public Spaces to conduct community engagement and develop a new market layout with space for more vendors, and in 2014, the new market opened. The focus on wellness in the district predated the Flint water crisis; Hurley Children’s Clinic’s Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha was the one who blew the whistle on elevated levels of lead in children, and today she prescribes fresh fruits and vegetables sold at the market to help counteract the effects of lead.

Our findings from these three communities, presented in the following research briefs, reveal that the nuances in how we plan, program, and govern public spaces have far-reaching impacts for equity— shaping the amenities and services people have access to, the spaces available to them to grow a business, and the connections forged between people and places. As cities seek rebuild equitably from the pandemic, they should leverage these insights to ensure that public spaces can fulfill their role as critical community infrastructure that supports more equitable and resilient communities, cities, and regions.

Cover photo courtesy of Downtown Albuquerque Main Street: Pictured is Civic Plaza in Downtown Albuquerque.

The authors thank Joanne Kim for her excellent research assistance on this series. They express their sincere gratitude to the community stakeholders who participated in research interviews and focus groups. They also thank Lola Bird, Lavea Brachman, Karriane Martus, Steve Ranalli, Nate Storring, and Jennifer S. Vey for their review of various drafts of the series. Any errors that remain are solely the responsibility of the authors.

[i] Braubach, Matthias, et al. “Effects of urban green space on environmental health, equity and resilience.” Nature-based solutions to climate change adaptation in urban areas. Springer, Cham, 2017. 187-205: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5_11; Carmona, M. Place value: place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. Journal of Urban Design, 24(1), 1–48, 2019: https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1472523; Gaynair, G., M, Treskon, J. Schilling, and Velasco, G. Civic Assets for More Equitable Cities. Urban Institute, August 2020: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/civic-assets-more-equitable-cities.

[ii] Eldridge, M., K. Burrowes, and P. Spauste,Investing in Equitable Urban Park Systems. Urban Institute: July 2019. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/investing-equitable-urban-park-systems; Active Living Research. Do All Children Have Places to be Active? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2011: https://activelivingresearch.org/sites/activelivingresearch.org/files/Synthesis_Taylor-Lou_Disparities_Nov2011_0.pdf

[iii] Gaynair, G., M, Treskon, J. Schilling, and Velasco, G. Civic Assets for More Equitable Cities. Urban Institute, August 2020: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/civic-assets-more-equitable-cities; Eldridge, M., K. Burrowes, and P. Spauste,Investing in Equitable Urban Park Systems. Urban Institute: July 2019. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/investing-equitable-urban-park-systems. Rigolon, A., and J. Christensen: Without Gentrification: Learning from parks-related anti-displacement strategies nationwide. ULCA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, 2019: https://www.ioes.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Greening-without-Gentrification-report-2019.pdf.

[iv] Knight Foundation. Measuring Progress Toward Downtown Revitalization and Engaging Public Spaces: A Review of Existing Research. August 2020: https://knightfoundation.org/reports/measuring-progress-toward-downtown-revitalization-and-engaging-public-spaces-a-review-of-existing-research/.

[v] Jennings, Viniece, Matthew H. E. M. Browning, and Alessandro Rigolon. Urban Green Spaces. Public Health and Sustainability in the United States. Springer Briefs in Geography, 2019: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-10469-6.