MEDIA RELEASE

Wealth and Income Inequality Rising Less Rapidly than Estimated by Piketty, Others, New Brookings Research Finds

Improved estimates emphasize importance of methodology, macro data in calculating top wealth and income shares; implications for effectiveness of redistribution policies

Wealth and income concentration at the top has risen by half as much in recent years than previous estimates and is rising less rapidly, according to a new paper presented today at the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity (BPEA). The uncovering of methodological weaknesses and thus mismeasurement in the most widely-cited estimates of wealth and income held by the top 1 present has implications for income distribution public policies.

In “Measuring income and wealth at the top using administrative and survey data,” Jesse Bricker, Alice Henriques, and John Sabelhaus of the Federal Reserve Board and Jacob Krimmel of the University of Pennsylvania reconcile widely divergent estimates of increases in wealth and income, demonstrating how specific choices in data sets and methodological decisions affect the levels and trends. They find that while the concentration of wealth and income of the top 1 percent has indeed increased since 1992, it increased far less than prior research has found.

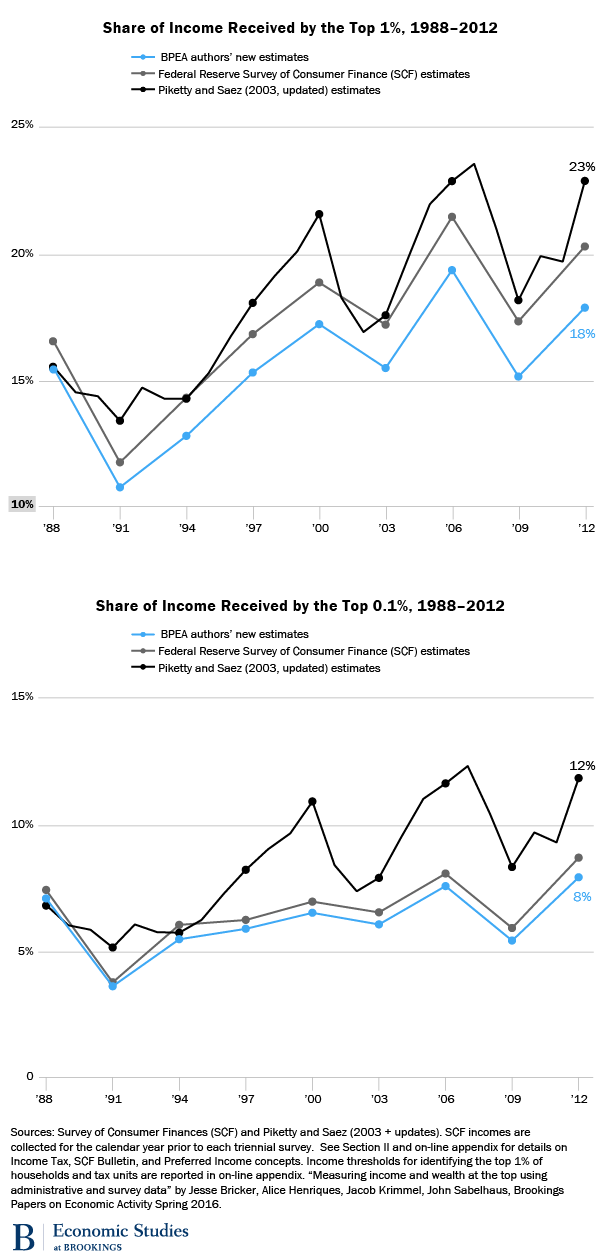

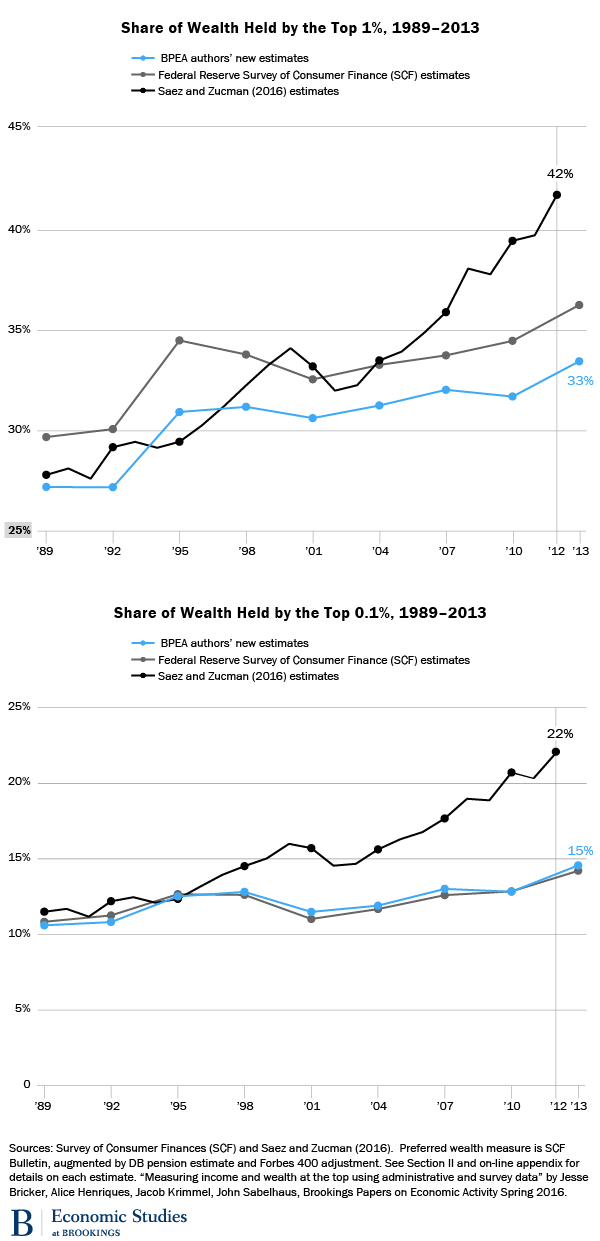

A widely-cited estimate from Saez and Zucman (2016) estimates the share of wealth held by the top 1 percent increased 13 percentage points, from 29 percent in 1992 to 42 percent in 2013. The new, more robust Bricker et al. research shows income shares rising only 6 points over that same time period, to just under 34 percent in 2012. Similarly, Piketty and Saez (2003, updated) estimate the share of income held by the top 1 percent increased 10 points, from 13 percent in 1991 to 23 percent in 2012, while the new Bricker et al. research shows only a 7 percentage point increase to 18 percent in 2012.

The new estimates use two main sources of data at the individual level (micro): administrative tax records and the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF) household survey. However, the authors’ note that their efforts to reconcile existing estimates rely on available macro (aggregate) data, which they believe is key for understanding top wealth and income shares because changes in the aggregate composition of income and balance sheets over time affect for whom the micro data are comprehensively capturing. Methodology, in addition to data sources, has also played a key role in overstated estimates of top wealth shares inferred directly from administrative tax records, they note. The mismatch between micro income and macro wealth concepts and coverage leads to a bias in ‘capitalization’ factors used to infer top wealth shares.

Although the new estimates are gleaned from the best available data sources, the authors point out that the data used for their preferred estimates are still likely not fully capturing comprehensive wealth and income measures. The omission of many employer-provided benefits, health transfers, and other forms of substantial income, like Social Security, from most data sources makes it difficult to accurately examine inequality across the entire income distribution.

“One specific concern is that wealth concentration may feed on itself, if undue political influence is being exercised by those who can (sometimes independently) finance election campaigns, and generate an even more favorable tax or regulatory environment for themselves in subsequent periods,” they write. “The primary concerns about the effects of rising wealth inequality involve investment and economic growth. Rising wealth concentration may intensify financing constraints for the non-wealthy, affecting investment in education, entrepreneurship, and other risk-taking for those with diminished resources. As with incomes, however, it is important to consider what may be driving estimates of top wealth shares, before recommending policies to address those trends.”

The mismeasurement has implications for policies designed to benefit families in the middle and bottom of the wealth and income distribution, they note. “The failure to properly measure the effects of government policies and market practices that disproportionately benefit families in the middle and bottom of the wealth or income distribution leads directly to overstatement of top wealth and income shares. Policies and practices such as social insurance and government investment in human capital generate real benefits and the debate is thus properly focused on the distribution of those benefits. If we measure only the costs of such policies and practices, without measuring the benefits, it becomes more difficult to make the case in favor of such policies in policy debates,” they conclude.