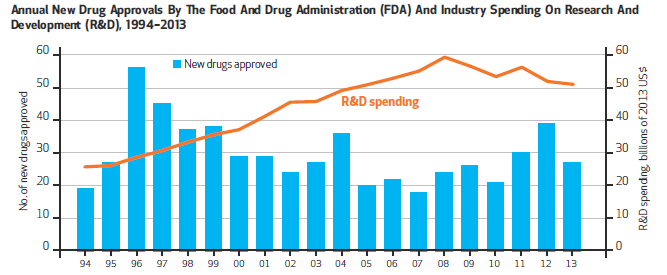

Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 41 new drugs and biologics for use in medical treatment, the highest number of approvals in 18 years. And yet despite this high, the output of new drugs over the past several decades has demonstrated fluctuating yet flat trends in number of approvals. At the same time, pharmaceutical industry R&D spending continues to rise dramatically, leading many to question the efficiency of the drug development and regulatory review process.

In a new Health Affairs paper (subscription required) we contend that traditional metrics linked to biomedical innovation—i.e., annual number of drugs approved, and costs and success rates at each stage of drug development—do not fully characterize the innovation process or its impact on health outcomes and health care costs.

Graphic courtesy of Health Affairs

These metrics fail to fully examine the factors that truly influence innovation (see Figure 1). For example, Figure 1 provides little understanding of the significance of new drug counts, the potential disconnect between R&D spending and drug approvals, or what the impact of approved drugs might be for patients. Further, these metrics do not allow policymakers and researchers to understand which factors may be influencing the success (or failure) of certain drugs and/or what additional disease areas or conditions might benefit most from new policy efforts or legislative action.

For instance, over the last two weeks alone, we have significant policy proposals, including the U.S. House of Representatives’ 21st Century Cures initiative and the Obama Administration’s Precision Medicine Initiative. These ideas and others like them need to be supported by data-driven evidence to influence meaningful and effective policy change.

An invaluable step for better understanding innovation would be to expand beyond analyzing approved drugs into surveying the universe of unsuccessfully developed investigational compounds that stalled or failed in development. For instance, are there common factors that lead to failure? Are there additional lessons we can learn from therapeutic areas with better track records? Answering these questions, and removing the “winner’s bias” that can be inherent in research that only analyzes approved drugs would be a significant step forward.

Encouraging Better Tracking and Data Analysis

How can we begin to build a more robust database and research framework to improve measurement of innovation?

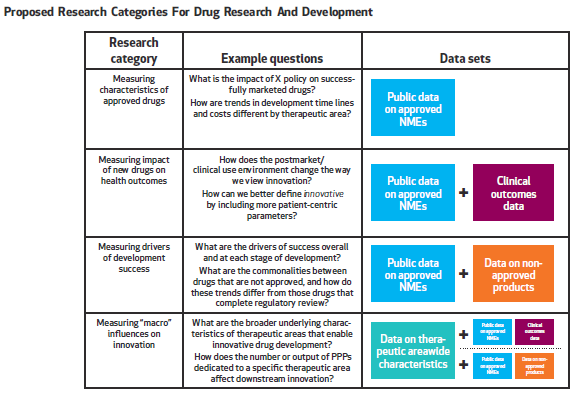

In our paper written with colleagues from the Deerfield Institute, we emphasize the importance of a new database to address major gaps in data collection and analysis that can be used broadly across stakeholder groups. As depicted in Figure 2, we believe the database should address four major categories of research that measure:

- Characteristics of approved drugs that go beyond basic counts of new drugs, and incorporate factors such as disease area, funders, clinical development time and regulatory review time;

- Impact of new drugs on health outcomes, including patient’s ability to access the drug, patient health outcomes and the effect of new drugs on cost of care;

- Drivers of development success that highlight not only why a particular drug was approved, but also why investigational drugs that do not reach regulatory approval stalled or failed; and

- “Macro” influences on innovation, including data on therapeutic/disease area characteristics, independent research efforts by patient advocacy groups and the effect of regulatory and legislative actions.

Graphic courtesy of Health Affairs.

As we discuss in the paper, however, simply seeking more detailed analyses of approved drugs will not paint the entire picture of clinical development and regulatory review. Another important step, and arguably one that is a bit further down the road, is to develop more standardized ways to measure true innovation and the actual impact new treatments have for patients across multiple disease areas. Without finding a better way to link trends in development and approval to measurements of downstream effects, we risk continuing to define innovation in a vacuum.

In the end, we can only ever improve biomedical innovation if we better understand when, where, and how it succeeds or comes up short. Our team at Brookings feels the time is right to begin working collaboratively toward such an aim.

Commentary

How can we better measure biomedical innovation?

February 4, 2015