Recent events have made clear the pervasive and continuing animus towards various race and ethnic groups in the U.S. The current COVID-19 epidemic has become the latest impetus for acting on old biases of “otherness” or not belonging towards Asians and baselessly holding them responsible for the pandemic. It has been reported that residents of border towns near the Navajo Nation have targeted Native Americans in their insults as vectors of COVID-19 and demanded that they return home to the reservation. Front-line workers, many Black and Hispanic, who have long endured the disrespect of entitled customers, are now dealing with the ire – racist epithets and even physical assault – of those who are angry at being required to cover their mouths and noses while shopping. In the absence of systematic data on this topic, we are left to these anecdotal instances, and that makes it much more difficult to identify pervasive patterns and behaviors in society. In the media, these instances are often noted, but they can easily be dismissed as outliers or attributed to a single “bad actor.”

Even when data are collected, smaller race groups are often not included in national surveys or have so few observations that separate analysis cannot be conducted. These small populations tend to be clustered in an “other” category.

From a scientific point of view, this practice is not generally viewed as problematic. If a “representative sample” of 2,000 respondents happens to completely exclude Alaska Natives this may not raise eyebrows because the population of Alaska Natives in the U.S. is less than one percent. This oversight, however, renders invisible the unique lived experience of this population. Not only is this a barrier to any policy discussion that might address the realities of this and other small groups, in the case of the experience of racism, it is a missed opportunity to understand racism as structural and pervasive as opposed to anecdotal and isolated incidents. In other words, if a survey can only explicitly and statistically demonstrate that African Americans and Hispanics report being the targets of discrimination and cannot describe the experiences of discrimination experienced by Khmer immigrants or Pacific Islanders then it is harder to understand that racial discrimination is a function of structural white supremacy and not the “problem” of a couple race groups.

A new survey which explicitly oversampled for small race and ethnic groups illustrates what is often missed in standard survey efforts. Research publisher AAPI Data and SurveyMonkey commissioned a new survey on racism, discrimination, and COVID-19 experiences for all of the large and small race and ethnic groups in the U.S. The survey illustrates the pervasiveness of racism toward all non-white groups — challenging the notion that the negative outcomes and experiences of one or two race/ethnic groups have only to do with the lived realities of those groups and supporting the idea that structural racism necessarily harms all Black and Indigenous people and other people of color, even when data sets render them invisible.

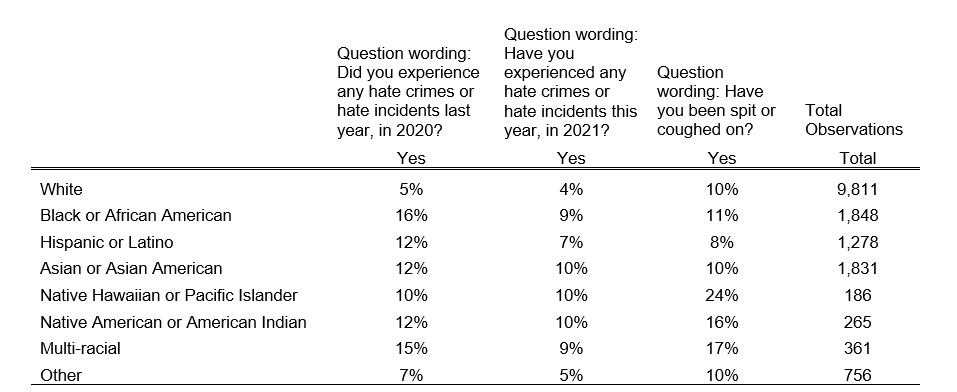

In the table above, we present some of the survey results to show the experiences of racism and hate crimes in recent years for different race and ethnic groups. The survey results, which oversampled for these small race and ethnic groups, indicate that approximately 5% of white respondents indicated having experienced any hate crimes or incidents in 2020. However, three times that proportion of Black and multi-race individuals report having experienced hate crimes in 2020. Other non-white groups also report experiences in 2020 that are at least twice that of the white population. In column two, which asks about experiences with hate crimes or incidents in 2021, we see that the incidents for all non-white groups are almost twice (or more) that of the white group. Overall, this indicates that hate crimes and incidents occur for all groups but disproportionately more for non-white individuals, suggesting a prominent role for systemic white supremacy in these incidents.

Finally, in column three and the graph below, we show the proportion of each race or ethnic group that indicate they have been spit or coughed upon. For the white, Black, Hispanic and Asian American groups, approximately 10% in each group reports having that experience. However, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders and Native Americans and multi-race individuals report substantially higher rates. In fact, the Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander reports almost one in four have had this experience. These results are quite surprising and unexpected; beyond that, in the era of COVID-19, these types of incidents may have dire health consequences.

It is thus reassuring to see a renewed call to broaden existing data collection efforts in order to identify the pervasiveness of racial disparities in employment, housing, and policing. President Biden’s recent executive order calls for the establishment of an Equitable Data Working Group and acknowledges that “a first step to promoting equity in Government action is to gather the data necessary to inform that effort.” It is imperative that the federal government collect and archive data on hirings, firings, mortgages and their interest rates, crime, and violence broken down by race and ethnic groups. This data foundation will be instrumental in identifying dynamic changes occurring across (and perhaps within) race and ethnic groups in the U.S. These actions should serve as useful examples for further data collection intended to address racial disparities and experiences in the U.S.

While this effort is aimed at federal government activities, it is an important start that should be expanded to other parts of the economy and society. In related efforts, the American Economic Association has identified the importance of better data collection for the measurement of racism and discrimination and continues to pursue independent efforts to achieve this goal. Increasingly, the lack of timely and accessible data is being recognized as an ongoing obstacle to identifying, diagnosing, and dismantling systemic racism in society.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

Commentary

Missed opportunities to understand racism in the COVID-19 era

May 13, 2021