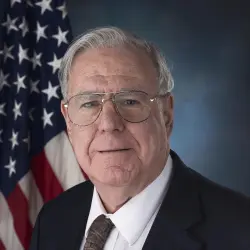

This piece was originally written for a forthcoming symposium from the National Academy of Social Insurance. The author was awarded NASI’s Robert M. Ball Award for Outstanding Achievements in Social Insurance in 2007.

The COVID-19 pandemic belongs to a class of newly salient risks against which America’s current collection of safety-net programs provides inadequate protection. These risks include major pandemic illness, increasingly frequent and severe natural disasters — including those associated with global warming — and the abiding threat of terrorist attack, including from lethal biological agents. Increasingly complex supply chains, expanded individual travel and labor migration, and the increasingly lethal instruments available to extremist and terrorist groups all contribute to these risks.

Until recently none of these risks seemed likely to cause national disruption. Now they do, and Congress needs to act to set up programs and procedures to deal automatically with them. Each risk threatens widespread economic disruption, mass illness, and death — and no current program is adequately designed to ameliorate their effects.

These newly salient risks should not sidetrack ongoing debates about how best to ensure that all Americans have financial access to health insurance and about the desirability of new safety-net programs such as guaranteed basic income, universal child care, and comprehensive long-term care. Nor should these risks be allowed to downgrade the need to assure adequate financing and other steps to strengthen Social Security, Medicare, and other social insurance programs. Indeed, the economic collapse caused by COVID-19 will move closer — by one or possibly two presidential terms — the depletion of the reserves of Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance.

COVID-19 has revealed serious shortcomings of the current safety net to cope with the consequences of mass unemployment, a problem that until now most of us thought fiscal and monetary policies could forestall. COVID-19 shows that such confidence is baseless. It shows, further, that current institutions are not well structured to cope with three major consequences of mass unemployment: loss of income, loss of access to health insurance, and disruption of public services provided by state and local governments.

Income Loss

The principal government programs assisting those with low cash income, whether endemic or resulting from mass unemployment, are the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, once called Food Stamps), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Unemployment Insurance (UI). These programs ramp up automatically when incomes decline, to help people individually and to maintain overall spending. Although SNAP and SSI rolls expand during periods of economic distress, benefits are low relative to most workers’ earnings, and asset tests mean that most of the newly jobless are ineligible for SSI benefits and in some states for SNAP. UI is quickly available, regardless of past income or assets, but it normally serves only a minor fraction of the unemployed even in normal times. Most workers are not — or think they are not — eligible. Many find compliance requirements onerous and do not apply.

As COVID-19 triggered unprecedented increases in unemployment, expenditures under these three programs rose automatically, but only enough to replace only a small share of lost income. COVID-related claims overwhelmed state UI offices. Inadequate staffing, outmoded computer systems, and insufficient data made it impossible to promptly process applications and to increase benefits by anything other than a lump-sum amount. The result was hastily enacted and clumsily administered legislation that enabled a huge increase in payments through the UI program which spared millions an abrupt slide into poverty. But this legislation is scheduled to expire long before economic recovery is underway and as of this writing (June 2020), it is unclear whether that legislation will be extended, even in modified form.

Because other COVID-like economic shocks must be regarded as likely, it is imperative for Congress to pass permanent legislation establishing a nationwide framework for economic assistance in a future emergency. It is at least as important to invest now in the data and computer capacity necessary to provide aid promptly and in a targeted manner. As each future crisis will have its own characteristics, Congress will likely see fit to modify any legislation it passes now. But it would be far better to have in place both a framework for action and the administrative infrastructure to carry it out before a crisis hits than to continue cobbling together responses in haste.

Whether such aid is provided directly to people or is channeled in part through employers to forestall unemployment, advance preparations will enable aid to be provided more promptly and effectively than was the case with COVID-19. Just as closure of public gatherings early in 2020 would have saved tens of thousands of people from death and countless more from illness, so too the prompt provision of economic assistance can avoid or ameliorate mass economic hardship when future calamities strike.

Financial Access to Health Care

The linkage of health insurance coverage to employment for most Americans — other than the elderly, poor, and people with disabilities — is seen by many as an atavism. Under current policies, this linkage of jobs to health insurance means that COVID-19 will cause millions to lose coverage.

Although replacing the current system with government-managed health insurance would assure continuity of coverage, such a course has serious drawbacks. They include the need to massively restructure nearly one-fifth of the U.S. economy and to roughly double government spending and taxation — actions that would likely crowd out other important priorities for government action. In his essay in this compendium, Stuart Altman explains other problems associated with the termination of private insurance. He also reminds us that other countries achieve universal health insurance coverage through mixed private/public systems, some not fundamentally different from our own.

Fortunately, continuity of health insurance coverage can be ensured for all Americans by four steps that are less disruptive and costly than a total overhaul. Funding for Medicaid should be modified so that all states find it attractive to extend coverage up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Affordable Care Act marketplace subsidies should be deepened and made more broadly available. The small share of the legally resident population that might not enroll voluntarily in a private plan or be covered by a public plan should be automatically enrolled in a backup plan.[i] Coverage of undocumented immigrants can be achieved by creating a path to citizenship. Such extensions — built on existing employer-sponsored coverage, Medicare, Medicaid, and other public health insurance programs — would ensure that every American has insurance regardless of employment status or economic circumstances.

State and Local Public Services

The fiscal vulnerability of states and localities to economic downturns is well understood. Income and sales tax revenues decline when economic activity slows. When people lose jobs, however, demand for most state and local government services remains constant or actually increases. Furthermore, states operate under balanced-budget requirements. Deficits cause credit-rating agencies to downgrade state debts, which boosts future borrowing costs. Previous economic downturns have rapidly depleted rainy-day funds and forced painful curtailment even of essential services. The COVID-19 downturn is much larger than any post-World-War-II recession. The full consequences for state and local finances have yet to be determined, but current projections indicate a fiscal gap of more than $615 billion over the period from 2020 through 2023.[ii]

Without sizeable assistance from the federal government, disruption of state and local government services will be massive. Such federal assistance can take several forms. Analysts have long recommended countercyclical revenue sharing, with grants to all states triggered when unemployment exceeds a threshold. Until now, the need for such aid has not been seen as sufficient to drive resolution of the analytically complex and politically difficult decisions regarding triggers and allocation formulas. Widespread recognition of the newly salient risks that the nation faces should end delay in designing and enacting such legislation. Instead of, or in addition to, such general assistance, the federal government could increase grants for particular functions, such as elementary and secondary education or health care. The federal government could also vary its share of Medicaid spending based on unemployment rates, nationally or state-by-state, or on some other measure of economic activity.[iii] The framework for such assistance should be put in place now to deal with future contingencies.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has revealed serious shortcomings in the U.S. social safety net. It has not revealed serious shortcomings in our core social insurance programs. As has always been true — and as provided for under law — these programs require periodic scrutiny in light of continuing social and economic developments.[iv] Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance require periodic attention to align revenues and expenditures under the special discipline imposed by trust fund financing. But the challenges to the social safety net from large-scale disruptions such as COVID-19 lie elsewhere: in the perennially flawed UI program which requires ad hoc legislation every time it is needed most — during economic downturns; in the heightened importance of ensuring that unemployment does not cause loss of health insurance; and in the fragility of state and local finances when under assault by a major recession.

The author wishes to thank Gary Burtless for helpful comments and suggestions and Thomas N. Bethell for editorial assistance.

This piece has been revised to note that SNAP eligibility for newly jobless individuals varies by state and to include an updated estimate for state and local fiscal shortfalls for 2020-2023 (see footnote iii).

[i] Matthew Fiedler, Henry J. Aaron, Loren Adler, Paul B. Ginsburg, and Christen L. Young, “Building on the ACA to Achieve Universal Coverage,” New England Journal of Medicine, May 2, 2019, pp. 1685-1688.

[ii] Elizabeth McNichol and Michael Leachman, “States Continue to Face Large Shortfalls Due to COVID-19 Effects. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 15, 2020, at https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-continue-to-face-large-shortfalls-due-to-covid-19-effects

[iii] Matthew Fiedler and Wilson Powell III, “States will need more fiscal relief. Policymakers should make that happen automatically,” Brookings, Thursday, April 2, 2020 at brookings-edu-2023.go-vip.net/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2020/04/02/states-will-need-more-fiscal-relief-policymakers-should-make-that-happen-automatically

[iv] See, for example, Henry J. Aaron, “How to Keep Social Security Secure,” The American Prospect, May 1, 2018, at www.prospect.org/infrastructure/keep-social-security-secure

Commentary

The social safety net: The gaps that COVID-19 spotlights

June 23, 2020