A key question confronting banks and regulators is whether current capital ratios are sufficient for banks to lose some capital when the next recession starts— as they inevitably will when loan losses build and revenues decline—and still have enough capital to stay above minimum requirements in the following year’s stress test and to prevent a sharp contraction in credit to households and businesses.

In a recent paper, we found that the stress tests, as intended, have supported higher capital ratios and helped to counter procyclicality as the economy has expanded so that banks will be resilient to a downturn and be able to continue to lend. We found that the requirement that banks prefund their proposed shareholder payouts—dividends and share repurchases—has been increasingly important as payouts have risen significantly with earnings in recent years. The Federal Reserve has proposed to stop the prefunding of share repurchases in its “stress capital buffer” (SCB) proposal.[1] Our analysis indicates that if the Fed were to stop requiring prefunding, it should offset what would be a decline in capital requirements for the global systemically important banks (GSIBs) with a GSIB surcharge or countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) to at least maintain current capital ratios.

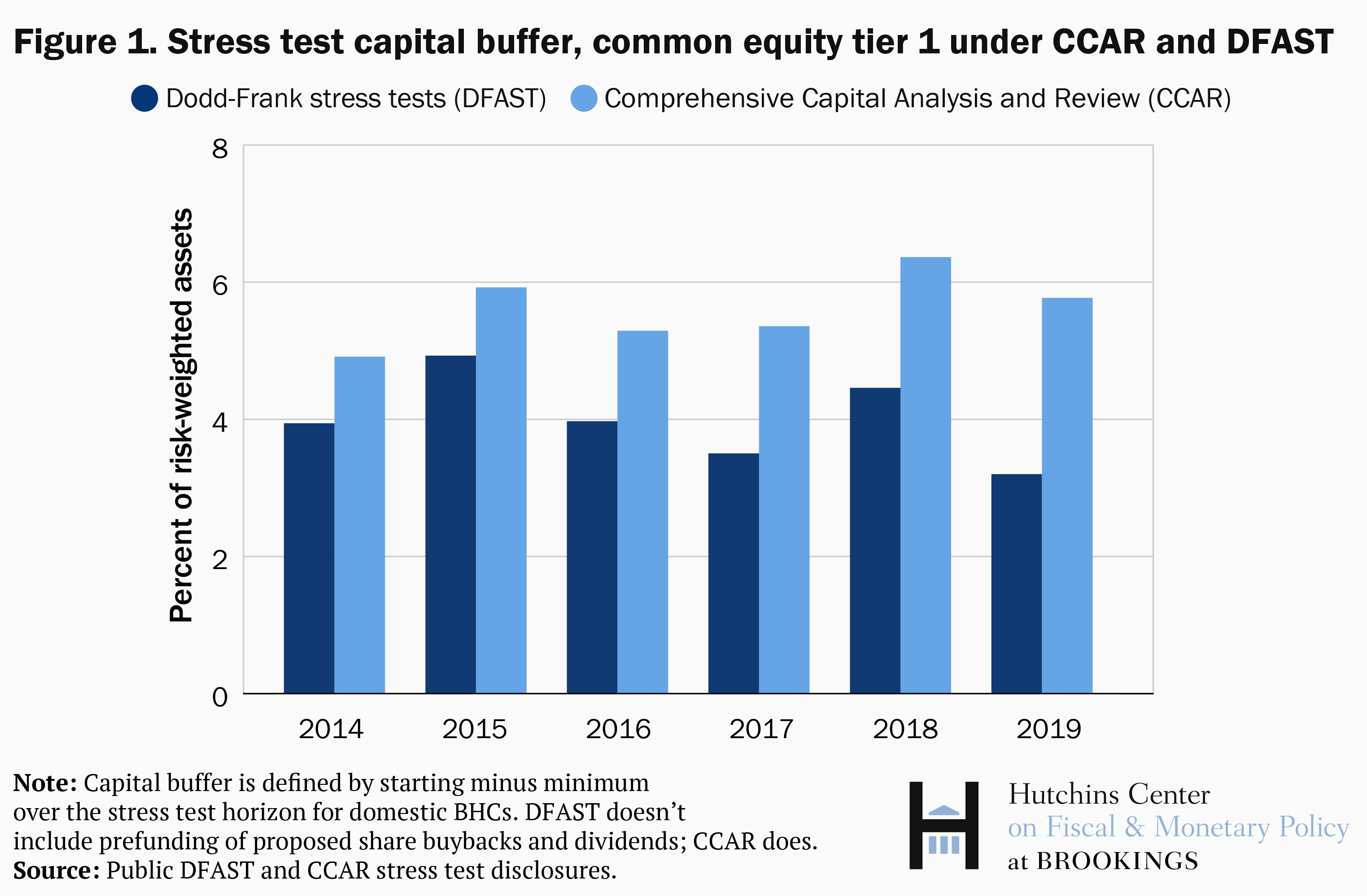

Capital requirements from the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) were almost 6 percent in 2019 for the domestic banks, up from 5 percent in 2014 (Figure 1).[2] Capital buffers from the Dodd-Frank stress tests (DFAST), which do not include proposed share repurchases and dividends, fell on net over this period, suggesting a decline in estimated net losses. While the macroeconomic scenarios are designed to be countercyclical, with greater increases in the unemployment rate when it is low, they have not on their own led to higher net losses. Rather, it is the prefunding of proposed shareholder payouts which has been a more powerful countercyclical force in recent years.

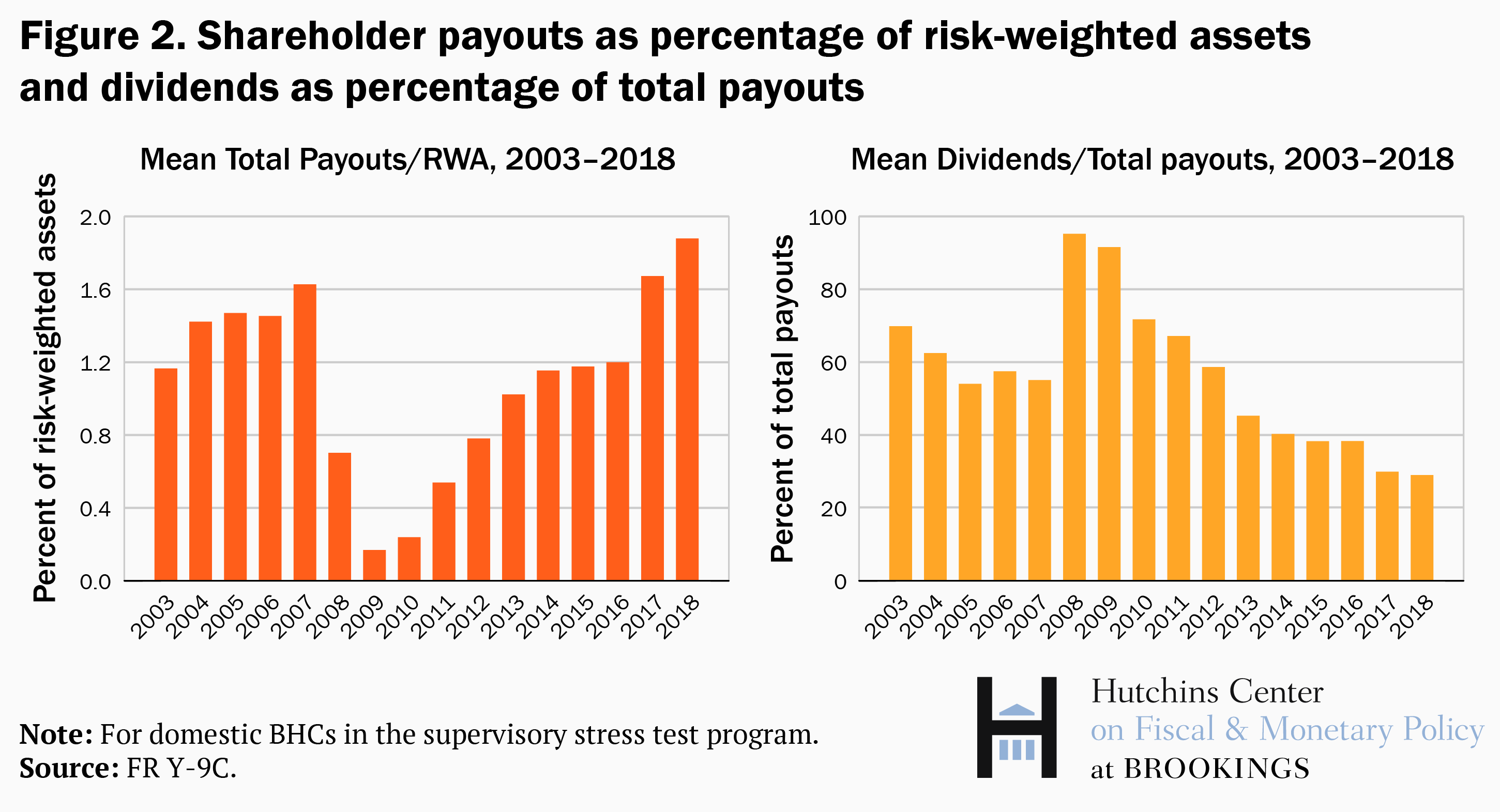

While banks’ proposed payouts are confidential, actual payouts – dividends and share repurchases—by the stress-tested banks reached more than 1.8 percent of risk-weighted assets (RWA) in 2018, almost double the rate in 2014 (Figure 2, left panel). The good news is that banks have improved their capital planning processes because of the stress tests. Share repurchases rose much more quickly than dividends, leaving dividends at 30 percent of shareholder payouts in the past couple of years, well below its share in pre-crisis years of more than 50 percent (Figure 2, right panel). Thus, banks are better positioned to reduce payouts because scaling back share repurchases does not have the same negative effect on stock prices as does a cut in dividends.

We use a simple example to evaluate whether banks have sufficient capital for a two-period scenario in which a recession starts and a new CCAR is specified at the beginning of the following year.[3] The new CCAR would be important at such a juncture because market participants and regulators will want to be assured that banks are adequately capitalized and would not unduly restrict credit if the recession were to continue, which could intensify downward pressures.

In the first year of a recession, bank capital ratios would fall as losses increase and revenues fall. As firms would remain above minimum regulatory capital standards, we assume they will continue to pay dividends but shut off share repurchases after two quarters. Federal Reserve supervisors would then specify a new scenario for the CCAR. As specified in guidance, the new macro scenario would have a smaller increase in the unemployment rate than in the previous year’s scenario before the recession started; scenarios are designed to be less severe when underlying economic conditions are worse. Moreover, we assume that dividends are maintained (and not increased) and share repurchases remain at zero. That is, we assume that shareholder payouts are pulled back fairly quickly and sharply.

Based on the current average tier 1 common equity ratio of 12.3 percent for the GSIBs and the assumptions above, their capital ratio after a recession and under the subsequent CCAR scenario would have a good chance of falling below the minimum requirement of 4.5 percent. Thus, we argue that the average GSIB is ready for the next recession only if it shuts off repurchases quickly once a downturn is underway.

The potential tightness of this constraint would be an incentive for GSIBs to restrict lending as soon as a recession starts, which could lead to the situation that countercyclical features of stress test requirements are designed to avoid. While supervisors would reduce the severity of the macro scenario, as specified in the guidance for this situation, they likely will be constrained by investors who may be looking for strong assurance at that moment that banks can weather a severe recession or an intensification of stresses.

In contrast, non-GSIBs start with capital ratios almost as high, 11.9 percent, but have significantly lower expected losses. In the same two-period scenario, they would remain comfortably above minimum requirements based on the range of estimated losses in the stress tests from 2014 to 2018.

The Federal Reserve has proposed to relax the prefunding requirement for share repurchases in its SCB proposal, but to add the GSIB surcharge to the minimum requirement. The GSIB surcharge would help to prevent capital ratios from falling. But the GSIB surcharge is constant, while prefunding share repurchases provides a better offset to procyclicality, since they increase in good times and decrease in bad times. Another alternative would be to raise the countercyclical capital buffer, which differs from the GSIB surcharge because it can be released in bad times, which would then relax constraints on payouts and executive compensation.

The stress test requirement to prefund shareholder payouts has been important to raising capital ratios and to counter procyclicality. The SCB proposal eliminates prefunding share repurchases, but also has an objective to maintain capital near current levels. Our analysis suggests GSIBs need to at least maintain capital ratios near current levels so they are ready for the next recession and not incentivized to restrict credit. A GSIB surcharge or countercyclical capital buffer, or a combination, are alternatives to prefunding payouts to achieve this important goal.

[1] The proposed stress test capital buffer is designed to integrate the forward-looking stress test results from the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) with the Board’s non-stress capital requirements, and thus simplify the capital rules for the large banks. The Board estimates that the proposed changes would generally maintain or increase the amount of capital required for GSIBs and generally decrease modestly the amount of capital required for most non-GSIBs. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20180410a.htm

[2] Banks’ proposed plans for dividends and share repurchases are incorporated into CCAR, whereas only dividends at the past year’s pace are in the Dodd-Frank Act stress tests (DFAST). The same macroeconomic and financial scenarios are used in CCAR and DFAST. Thus, if the minimum quarters under the stress horizon are the same for DFAST and CCAR, the estimates of net losses are the same, and the higher buffer for CCAR relative to DFAST each year approximates proposed share repurchases and dividend increases.

[3] While the current stress test exercise considers a nine-quarter horizon, the recession and shock to the trading book is concentrated in the first year, and the economy recovers in the second year. Thus, capital requirements implied by the capital ratios at the end of the nine quarters have been lower than capital requirements implied by the capital ratio at the minimum over the stress test horizon. This exercise, in contrast, assumes banks incur losses in the first year in an actual recession, and then considers how banks would fare in another recession specified in the next CCAR.

Commentary

Prefunding shareholder payouts is a strong countercyclical force in bank stress tests

July 22, 2019