Much has been written about de-industrialization; the loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States as imports from and other low-income countries rise. But “de-institutionalization” may be more disruptive in the long term.

While manufacturing jobs in the U.S. might return as wages rise in low-income countries, technologies like 3-D printing advance, and trade barriers are erected, de-institutionalization will be much harder to slow down or reverse.

So what is it?

The latest example is the government reorganization plan issued by the Trump administration on June 21, Delivering Government Solutions in the 21st Century: Reform Plan and Reorganization Recommendations. The 132-page report is a roadmap for shrinking the federal bureaucracy in the name of efficiency, but it is clearly designed to be a political gift to the Republican Party’s anti-government base.

The basic idea behind the de-institutionalization phenomenon is that the rise of the west over the past three centuries has been powered by institutions: the emergence of nation-states, the adoption of constitutions and laws and courts, the elaboration of bureaucracies, the formation of corporations, the proliferation of civil society organizations, the evolution of schools and universities, the founding of the United Nations, a multitude of international treaties, and so on.

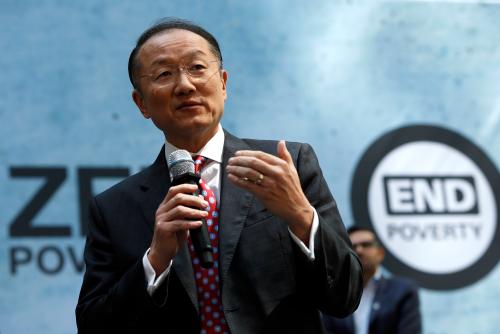

Today, many, if not most, of these institutions are on the defensive—they are having a hard time meeting user expectations and struggling to stay relevant. The Trump administration is the most visible threat to institutions today, but it’s not the first and far from being the only one.

There are two obvious drivers of de-institutionalization and one not so obvious one.

The first driver, it can be argued, is old age. Every institution ages. Most institutions are reformed from time to time, but generally they seem to lag behind the curve of history. Most institutions also tend to become more complex as they age, as amendments and interpretations accumulate over time. One spectacular example is the income tax code in the U.S. As a piece in Business Insider highlighted, from around 400 pages in 1913 after the 16th amendment was ratified, the tax code grew to 73,954 pages for the 2014 tax year.

A second driver is technology. From the earliest civilization, technology has been the preeminent source of change: the wheel, the printing press, electricity, etc. New technologies render obsolete the ways people live and force the emergence of different forms of social organization. Today we seem to be on the cusp of another era of great technological change: computers, robotics, and artificial intelligence being the most obvious forms. It is also obvious that these advances are disrupting our institutions in both the public sector and private sector.

The not-so-obvious driver of the current wave of de-institutionalization is social media. Creating a durable institution requires a degree of social consensus. Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms appear to be making it harder to reach the degree of consensus required to reform institutions as required to maintain their effectiveness going forward. It is also hard to build a durable institution in the face of great uncertainty, and social media appears to be contributing to the uncertainty that prevails around the globe these days.

What are the implications if the current de-institutionalization trend advances? At the pessimistic extreme, it is possible to imagine slipping into a “global dark age.” At the optimistic extreme, new institutions will emerge quickly enough to avoid global turmoil. In between is the more likely outcome of muddling along.

What should we do about it? There is little evidence to suggest that we are witnessing a process that can be stopped. It will be impossible to “save” institutions, as they now exist. It is wishful thinking to believe the United Nations will reform itself or to expect the U.S. income tax code to be substantially simplified—in the foreseeable future and in the absence of a crisis. The best we can do is to start experimenting with new forms of institutions and build on those that look promising.

A world without institutions is the jungle, chaos. In the words of Thomas Hobbes, life will be “nasty, brutish, and short” unless our biology and chemistry labs learn how to change human DNA to make future generations un-greedy and peace loving.

Commentary

Institutions are under existential threat, globally

June 28, 2018