Many Americans don’t believe the government accurately measures changes in the prices of goods and services. While there is no evidence that the U.S. government manipulates its data, an interesting question is how much public perceptions matter. A paper presented at the Spring 2016 Brookings Panel on Economic Activity conference finds that, at least in Argentina, consumers react in a sophisticated fashion to inflation statistics they believe to be biased, essentially “de-biasing the official data to extract all its useful context.” The authors – Alberto Cavallo, Guillermo Cruces and Ricardo Perez-Truglia – say these results are particularly useful for understanding the way households form expectations of inflation, an increasingly important ingredient in central-bank decision-making around the world.

Argentina: Where the inflation rate is made up and the prices don’t matter

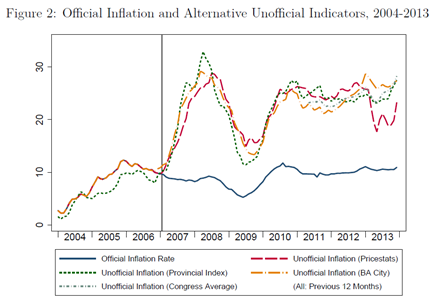

Argentina went through a major economic crisis in 2001-2002, and prices rose dramatically in the following years. Annual inflation surpassed 12% in 2005, up from 4% before the crisis. Facing scrutiny over rising prices, the Argentine government cleaned house at the National Statistics Institute (INDEC) in early 2007 and, until 2015, is widely believed to have manipulated official inflation readings; indeed, it was censured by the International Monetary Fund in 2013 for publishing misleading statistics. The figure below, taken from the Cavallo et al. paper, shows the gap between the official inflation measure and three unofficial (and more accurate) measures between 2007 and 2013.

Consumers could ignore the biased official statistics. Or they could blindly accept them as fact,

Rather than simply ignoring the official statistics or taking them at face value,” the authors say, “households seem to effectively adjust for the perceived bias using other available information.” In other words, consumers in Argentina did learn something from the official statistics, but they also relied on unofficial data. “In an environment with many alternative inflation indicators and a great deal of attention to the topic, people are sophisticated learners that can effectively process potentially-biased information,” Cavallo and co-authors conclude.

Using an on-line survey, the authors show that individuals in Argentina reacted intelligently to information about inflation, and they considered the source. Participants were told that the inflation rate was 10%, 20%, or 30%, and that the source was either official or unofficial. The inflation expectations of participants varied significantly based on the information they were given and its source. Participants’ inflation expectations responded to both official and unofficial measures, but reacted differently to the unofficial measures; they assumed both understated inflation, but assumed the official measures understated it more.

Lessons for policymakers

Inflation-measure manipulation in Argentina was largely ineffective. Most people were not fooled. Moreover, the authors say, “the policy of manipulating official statistics was counterproductive,” in part because consumers’ expectations of inflation rose when the official data showed an increase in inflation, but fell when the official data showed a decrease.

Of course, the authors concede, Argentina is an extreme case: Most countries, including the U.S., don’t overtly manipulate inflation statistics. But even in places where the official inflation measure is accurate, a large swath of the public is skeptical. A 2014 paper by the same authors found that nearly one of every three Americans doesn’t trust official inflation data. And those who didn’t trust the data had inflation expectations significantly higher than others. The difference, the authors say, could by driven by the way people adjust for what they perceive to be biases in the inflation data. Because consumers are more likely to be official readings suggesting inflation is rising than official readings that suggest inflation is falling, the authors conclude, “Governments should not only focus on providing information, but make efforts to reduce the perception of bias.”

Commentary

Considering the source: How we perceive inflation data

March 10, 2016