Earlier this month the Cuban government appealed to international companies to invest over $8 billion in 246 specified development projects. The 168-page Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment offers fascinating insights into the current distressed state of the Cuban economy – and into the competing development visions of its economic planners. Within the lengthy document, there are many assessments and proposals that suggest that Cuban authorities are prepared to dramatically open their economy to international capital, yet there are also many provisos that suggest a much more cautious strategy.

This is not the first time the Cuban authorities have issued a wish-list of projects open to foreign firms, but this edition is much more ambitious and reveals dramatic progress – and tensions – in officials’ thinking about their nation’s economic future.

Careful reading of the publication, prepared by the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Investment, will leave potential foreign investors with few illusions: Cuba will remain a state-driven economy dominated by large government holding companies and the authorities will dictate the direction and pace of change. Most foreign ventures will come with majority Cuban ownership.

But it is refreshing to find this admission: “The growth rates of Cuba’s GDP [gross domestic product] have been moderate and low, lower than the average for the region. In order to turn this trend around, accumulation rates higher than 20 percent are required to permit a GDP growth rhythm increase of 5 to 7 percent.” (Oddly, the details in this second sentence are omitted in the original Spanish version.) In that current national investment rates hover around 10 percent, to fill the gap annual foreign investment inflows must exceed by a large margin the $2.0 to 2.5 billion publically proposed by Minister of Foreign Trade and Investment Rodrigo Malmierca.

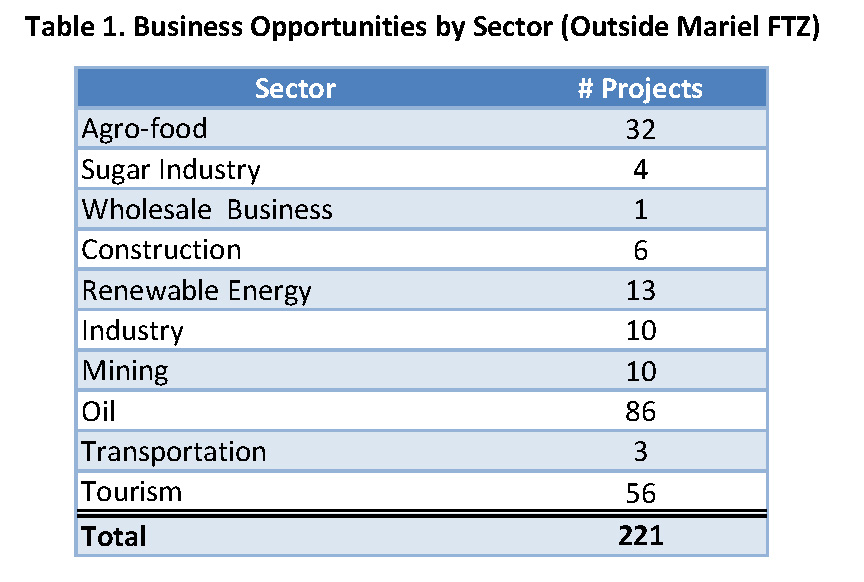

The government publication provides remarkably frank, data-rich surveys, sector by sector, of current production capabilities and shortfalls – must reading for specialists in the Cuban economy. It signals clear development priorities: energy (conventional and renewables), agriculture and tourism (Table 1[i]). On this, a consensus was probably easy to reach: investment in domestic energy production is critical to lessen a dangerous dependence on a faltering Venezuela. Cuba is spending way too much of its scarce foreign exchange resources on food imports, which is a genuine food security crisis. And tourism offers the only ready medium-term option for rapid growth in badly needed hard-currency earnings.

Tourism Management Contracts and Golf-Condo Destinations

The tourism section is particularly revealing of the internal tensions among Cuban policy planners: many attractive projects juxtaposed with well-delineated boundaries on the scope of foreign investment.

The potential tourism projects are sketched in striking detail. Cuba would like to build 21 new hotels in the Cienfuegos, Trinidad, Guardalavaca, Playa Santa Lucía and Covarrubias areas. The state companies that own hotels throughout the island are seeking new management contracts; 19 of them are for new hotels and 14 are for existing hotels and facilities.

Of particular interest to investors who might like to own condos on Cuban golf courses: a new government entity (belonging to the Palmares holding company), CubaGolf, will “promote the island as a golf-holiday destination.” CubaGolf is currently in negotiations with several foreign partners to form joint ventures to build and manage tourism-golf-condo complexes. One such potential joint venture in Holguin province, with a $380 million price tag, would boast two 18-hole golf courses, a 5-star hotel with 170 rooms and 1,300 housing units available for “in perpetuity” purchase. (Land ownership will not be transferable.) Hotel rates are estimated at $130 per night for a couple and a game of golf will be priced at $70 to 85.

The entrance sign of the Varadero Golf Club, around 84 miles from Havana.

Yet the government is setting aside some of the juiciest tourism opportunities for itself. In the high return-low risk locations of urban Havana and Varadero beaches, investor participation “will be the exception.” The safe yields are reserved for state-owned firms, especially Gaviota (linked to the armed forces), which the document proudly remarks “is the fastest growing hotel holding company.” Gaviota will restrict its foreign partners to management contracts and will demand that the partner provide not only construction financing but also international marketing, to assure profitable occupancy rates.

Burdensome Restrictions in Agriculture

The agricultural policies also suggest compromises between those planners who see the value of international engagement and private enterprise and those who fear that too many concessions risk undermining state controls as well as endangering the profitability of state-owned enterprises.

The section on agriculture makes this startling admission: of 6.3 million hectares of agricultural land, only 2.6 million hectares are being cultivated, despite years of official efforts to lure Cubans back to the land. But this document does not explore the adverse incentive structures responsible for this national catastrophe. Rather, we learn that the nation’s agro-industry is controlled by three large holding companies (GEIA, Cubaron and Coralsa) overseeing 108 enterprises. Most land is firmly owned by the state, allowing just 15 percent for private farmers and another 7 percent for farmer cooperatives.

Nevertheless, Cuba now seeks joint ventures in cattle, pork and poultry production, as well as in citrus, peanuts and shrimp farming. Specifically, Cuba would welcome a foreign partner willing to invest $10.3 million to create a “leading brand on the international level” of premium coffee, grown in selected micro-regions in the hills of Guantanamo province. Opportunities in agro-industry include greenhouses for vegetables, hog production, soy processing, confectionary facilities and dry yeast production.

Yet the sugar industry, however depressed, will remain firmly in the hands of the Cuban state. Only four mills will be open to foreign management contracts (expanding on the earlier management contract signed with a Brazilian firm to upgrade a sugar mill in Cienfuegos). The modest aim of each $40 million investment is “to recover” historic production levels.

The agricultural project list explicitly bars foreign investment from the tobacco and cigar industries (cigar marketing is already in the hands of a major British firm, Imperial Tobacco). Also excluded is lobster fishing and processing.

Energy and Industry Offerings

In the critical energy sector, Cuba is wide open to joint ventures in extracting petroleum from on-shore and off-shore blocks. But the goal is to raise the percentage of electricity produced from renewable sources from the current four percent to 24 percent by 2030. Foreign participation is welcome in hydro, biomass and solar, and, exceptionally, Cuba will allow 100 percent foreign ownership in wind farms, with an aim to invest $285 million to generate 174 megawatts in Guantanamo province and $200 million to generate 102 megawatts in Holguin province. But these energy ventures, whether partially or fully foreign owned, will have to sell their output at pre-fixed prices to state distribution systems.

Solar panels donated to Cuba by China in Parque Fotovoltaico.

Cuban consumers have suffered from shortages of beer and soda, for reasons rarely explained by the authorities. Now we have a strong hint at the cause: shortages of aluminum cans! The proposed portfolio of investments features a joint venture ($21.8 million) to produce 577 million cans, the principal clients being two existing joint ventures: the beer firm Bucanero and the bottled water and soda company Los Portales (Nestlé).

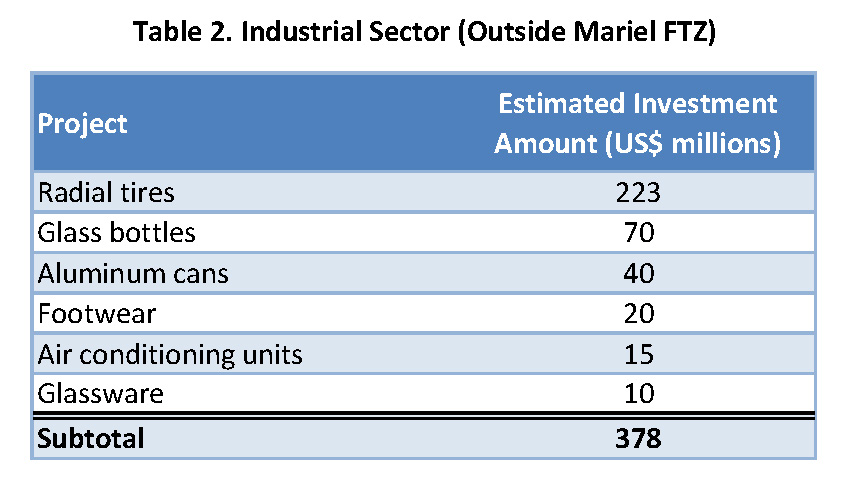

The proposed portfolio includes a wish-list for joint ventures in industrial production. Foreign capital is sought in these industrial projects:

Cuba would also like foreign investors to help produce computer desktops and tablets, with a $9.6 million investment. Current demand is estimated at a remarkably modest 75,000 computers (for a population of over 11 million).

The Mariel Free Trade Zone

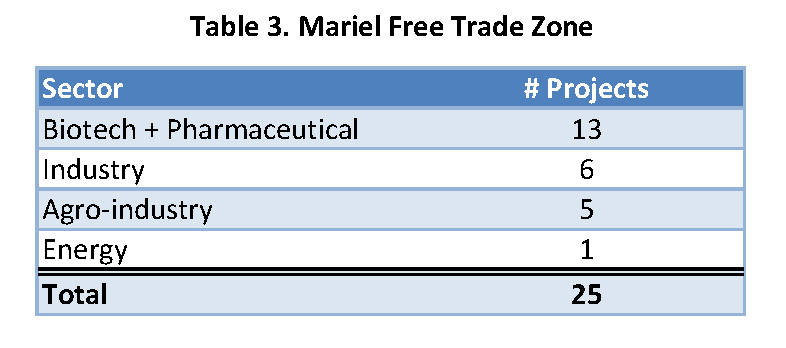

With the assistance of a major Brazilian construction company, Cuba has erected the Mariel Free Trade Zone (FTZ) west of Havana, facing the Florida Straits. Announced nearly a year ago with great fanfare, no major investments have yet appeared, although the government insists that many proposals are under serious consideration. For the Mariel FTZ, the Portfolio of Opportunities lists 25 export-oriented projects emphasizing medicine, agro-industry and light industry:

One partial explanation for the slow pace of project approvals at Mariel: the zone’s senior development officer, Ana Teresa Igarza, admitted to the Communist Party daily Granma that the industrial sites are not yet fully leveled nor are they hooked up to basic infrastructure!

But the problems run much deeper: previous Cuban efforts to launch free trade zones floundered on the requirement of hiring expensive labor through government employment agencies, and the continuing closure of the most logical export market, the nearby United States. (Interestingly, Portfolio of Opportunities omits reference to the U.S. economic sanctions that prohibit investments by U.S. firms and citizens.)

Cuba’s recently amended foreign investment laws appear to allow investors greater flexibility in setting wage scales, but this potentially promising reform, and its impact on labor costs, remains to be fully tested in practice.

Contradictory Impulses

Overall, Cuba’s Portfolio of Opportunities, with its many conditions and caveats, will raise eyebrows in the international investor community:

- Firms must “guarantee” foreign markets, and their business plans must provide projections on the impact on the balance of payments.

- In the selection of foreign partners, the Cuban government will “favor the diversification of different countries.”

- Privatization of state-held enterprises is ruled out (although the transformation of smaller state businesses into cooperatives in the service and construction sectors is proceeding apace).

- Foreign investment may partner with cooperatives but not with the emerging small-scale private enterprise. Readers searching the document for references to the much heralded self-employed “cuentapropistas” will be frustrated.

In sum, the 2014 Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment – with its contradictory combinations of frank analysis and attractive offerings and its demanding requirements and multiple barriers – opens an unusually transparent window into the on-going struggles within the Cuban elites: among those that wish to power ahead and integrate their economy into global capital and trading markets, those that adhere to the revolution’s founding statist nationalism and those that seek a middle road of carefully controlled change.

[i] All tables draw on data available in Ministry of Foreign Trade and Investment (MINCEX), Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment, Accessed November 20, 2014, http://www.cepec.cu/cepec/sites/default/files/Cuba_cartera-de-oportunidades_2014_ENG.pdf.

Commentary

Cuba’s Foreign Investment Invitation: Insights into Internal Struggles

November 21, 2014