Editor’s Note: In this blog, Carol Graham discusses the impact of inequality on well-being, particularly in Mongolia, which has experienced a dramatic economic and political transition in recent years. For a more detailed look at Mongolia’s well-being trends, see Graham’s latest paper.

After years of being a back-burner issue, inequality is on the U.S. public agenda, big time. America’s long-held reputation as the land of opportunity—the Horatio Alger society where anyone who worked hard could get ahead and where inequality was a sign of where these entrepreneurial individuals could go—is under duress. Study after study, including several by my Brookings colleagues Isabel Sawhill and Richard Reeves, show that not only has inequality increased, but social mobility is stagnating—at least for those cohorts at the bottom of the income distribution. And the fact that a book by French economist, Thomas Piketty, which warns of the dangers of increasing inequality but is also 700-plus pages, highly technical, and based on tax return data, has become a best-seller, says a great deal.

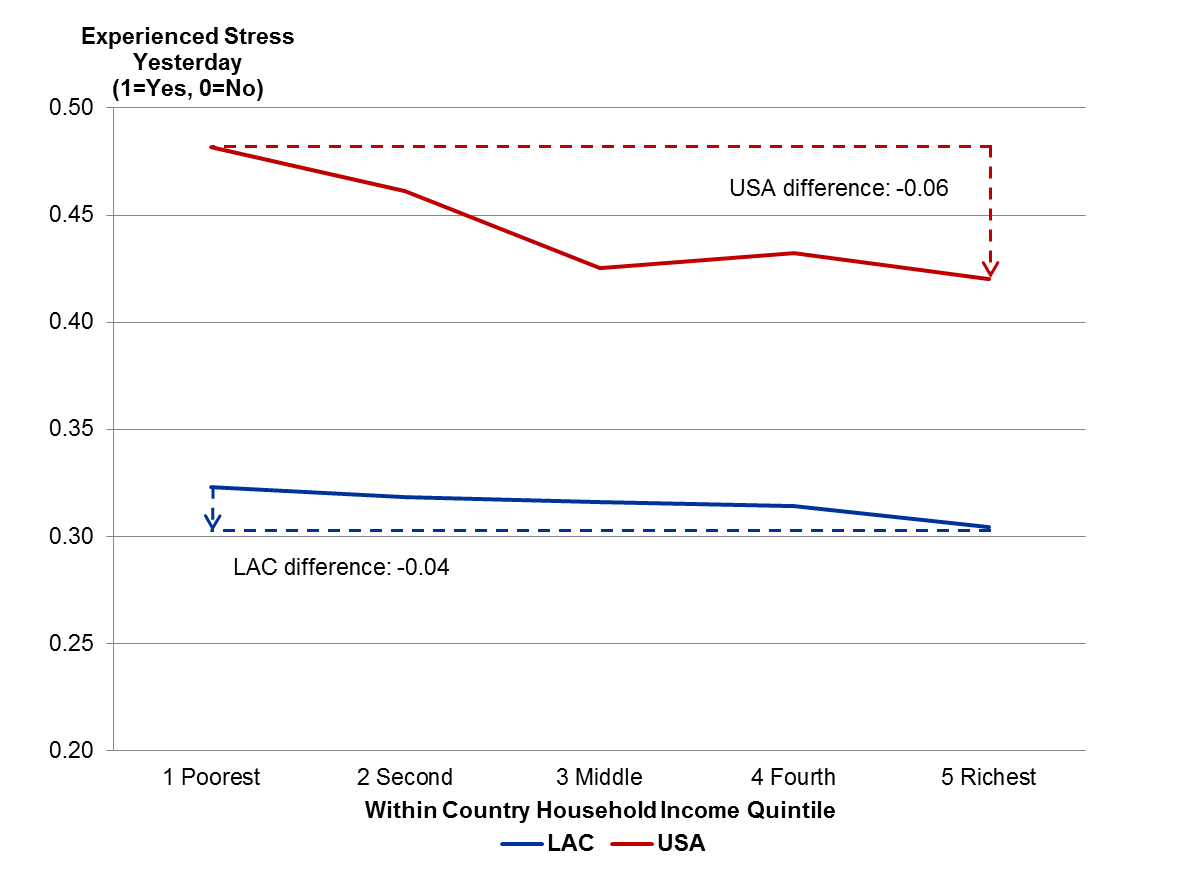

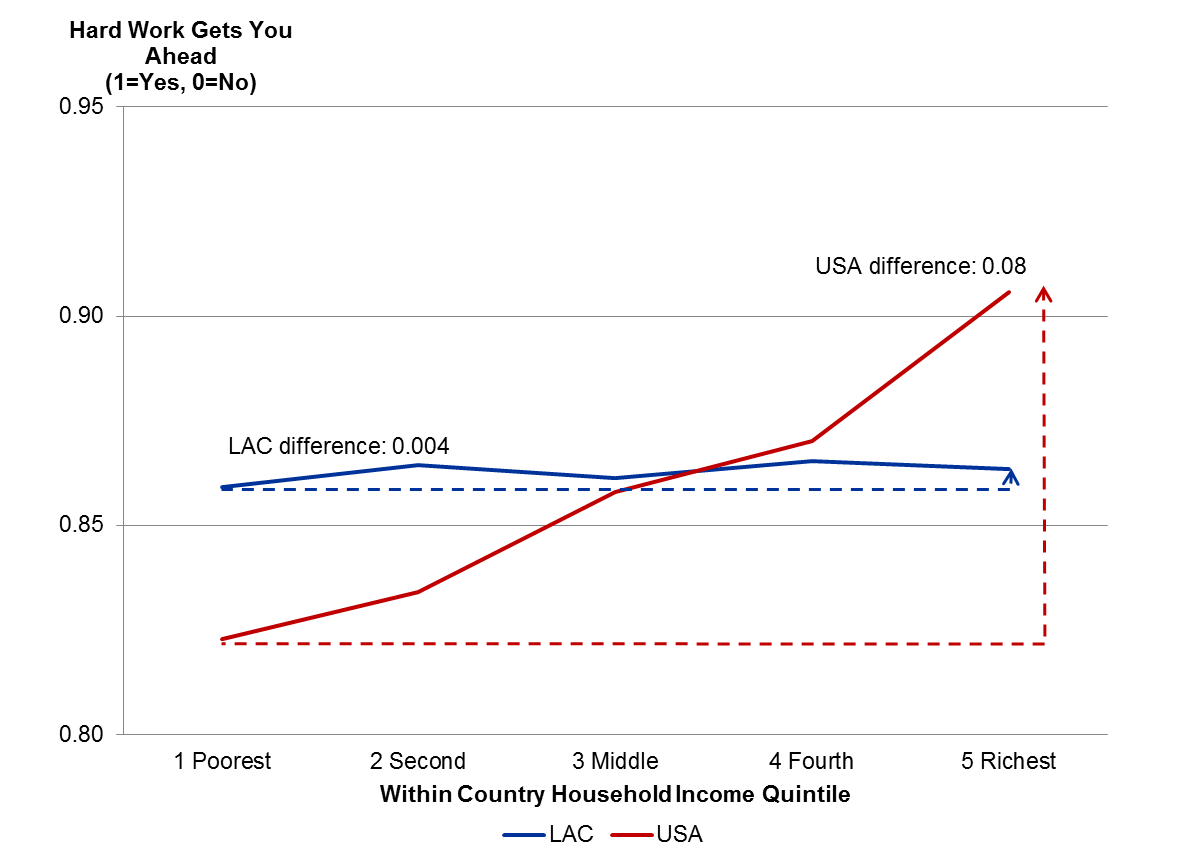

A stark view of two Americas has replaced that of the Horatio Alger society. Even the language of the two differs, as was described in a recent Upshot column by David Leonhart. The words that dominate poor places reflect short-time horizons and daily survival challenges, and range from “diets” and “diabetes” to “guns,” “hell” and “video games.” Those in rich places reflect vastly different opportunity sets and knowledge bases, and range from “iPads” and “baby joggers” to exotic travel destinations. My research on well-being finds large gaps in the levels of stress and life satisfaction experienced by the rich and the poor in the U.S. Indeed, we also find that the gaps in the stress levels of the U.S. rich and poor—as well as in their levels of confidence that hard work can get you ahead—are significantly larger than they are in Latin America—hardly a continent known for its equitable distribution or lack of poverty challenges.

Experienced Stress — United States vs. Latin America and the Caribbean

Belief in Hard Work — United States vs. Latin American and the Caribbean

Until recently, most studies on the effects of inequality on individual well-being found that the effects in the U.S. were either nil or rather surprising. A paper written a decade ago by Alberto Alesina and colleagues found that the only group in the U.S. that was made unhappy by inequality was left-leaning rich people! My earlier work with Andrew Felton finds that the welfare effects of inequality depend on what it signals. If it is a sign of potential future progress and opportunity, then it either has no effect or even positive ones. Yet when it is a sign of persistent advantage for some cohorts and disadvantage for others, then it leads to unhappiness and even social unrest in some contexts. Yet we still need to know more about how these channels operate.

Tuugi Chuluun, Sarandavaa Myanganbuu and I recently conducted the first extensive study of well-being in Mongolia, a country that has experienced a dramatic transition in both its economy and polity, including, in recent years, record levels of economic growth. We explicitly explored the role of inequality. The basic determinants of well-being in Mongolia are no different than they are in most countries in the world, with individual income, health, marital status and exercise, among other things, positively associated with life satisfaction. As in many other contexts, we found that average community income is negatively correlated with life satisfaction once respondents’ own incomes are accounted for. In other words, the higher the average income in your community is compared to yours, the less happy you are. The effect is particularly strong for respondents below median levels of income. Inequality in this instance is not a sign of future progress, but rather of being left behind at a time of dramatic economic change and progress.

In contrast, average community-level well-being (both life satisfaction and happiness in the daily experience sense) was positively associated with individual well-being across the board. While being around wealthier people may generate envy among some, being around happier people has positive externalities. This is an intuitive finding and fits with an increasing body of work on well-being that shows that higher levels of well-being are associated with better labor market outcomes, health, and social behaviors and interactions. In contrast, some of the same studies show that very low well-being levels—in particular high levels of stress and difficulties with daily life—lead to short-time horizons and obstacles to investing in the future. Thus, while wealthier neighbors are not necessarily good for you, happier ones surely are.

At a time that we are at loss for solutions to the increasing divide between the rich and the poor in the United States, maybe we can take a lesson from a far-away country and focus a bit more on the overall well-being of our citizens, including but beyond its material dimensions.

Commentary

Happy Neighbors are Good for You, Wealthy Ones are Not: Some Lessons from a Far-Away Country

September 15, 2014