Vladimir Putin has been elected as president of Russia yet again. He already served as president twice between 2000 and 2008, and immediately thereafter eased himself into the very powerful premiership, awaiting his next term as president. Now Putin will begin yet another presidential term, expected to last six years, since the Russian constitution was amended to permit a longer presidency. If he seeks and wins reelection in 2018, Putin could be president until 2024 and effectively rule Russia for more than two decades and would have served longer than any Russian leader besides Stalin.

Many are talking about the reasons for Putin’s comfortable margin of victory. Some point to the preference among many Russians for a strongman leader, one that provides them with stability. Others may cry foul about fraud at the polls or about the “Putin-fatigue” that has set in among the urban elite.

Yet this should not obscure three larger issues of significance for Russia and the world that transcend the details of yesterday’s elections.

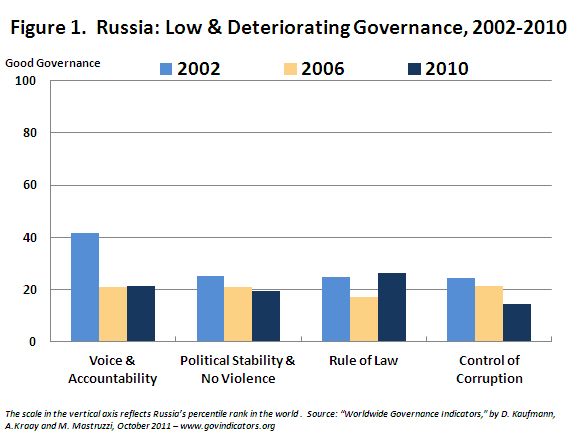

First, Russia’s governance standards have been declining rather markedly for about a decade. This deterioration and substandard governance can be seen in figure 1 for a number of dimensions of governance, as measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), and was discussed in a recent blog entry and conference presentation. In particular, consistent with increasing political repression (ostensibly in the name of “stability”), Russia has experienced a marked decline in voice & democratic accountability over the past decade.

The current presidential elections can be viewed in the context of a continuing decline in governance. The media and voters had to operate in a less-than-free political environment, where Putin exerted increasing control over the parliament and provinces, and where the emergence of any viable alternative was stymied.

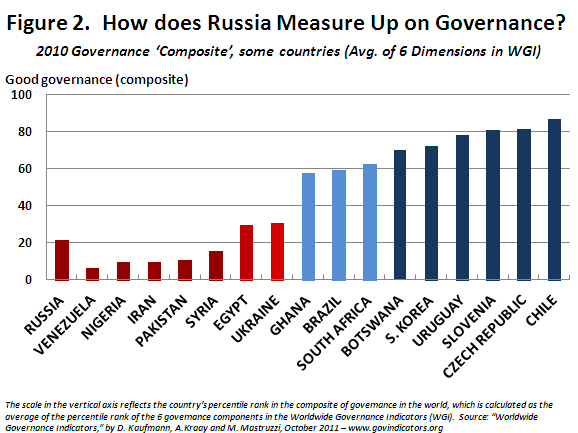

In fact, Russia’s governance rates extremely poorly when compared to the rest of the world. In figure 2, the governance “composite”, a simple average of the six dimensions of WGI, are shown.

The rough composite index of governance shows that Russia fails to measure up to the governance of countries that have attained relatively high governance standard, including several post-socialist countries (now fully integrated into Europe) and South America.

By contrast, the presence of Ukraine— which has also recently experienced a decline in democratic governance[1] — or worse, Pakistan, in Russia’s governance cohort illustrates that there is a group of countries where good governance did not materialize during transition.

Second, for quite some time Russia has wrestled with endemic corruption, which has worsened over the past decade, as seen in figure 1 above. High levels of corruption pervade the executive, legislature, judiciary and private sector interactions with the public sector.

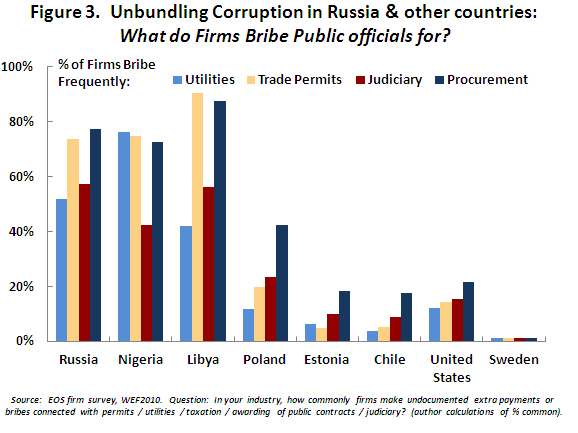

As seen in figure 3, for every type of bribery a very high proportion of enterprise managers report frequent bribery, comparable with rates in countries like Nigeria and Libya, and sharply contrasting the much lower frequency of bribery in many other countries.

Cronyism plays an important role in Russia and those close to Putin in the Kremlin have benefitted handsomely. One particular source of high-level bribery is public procurement since the most firms in Russia have to pay bribes to obtain contracts.

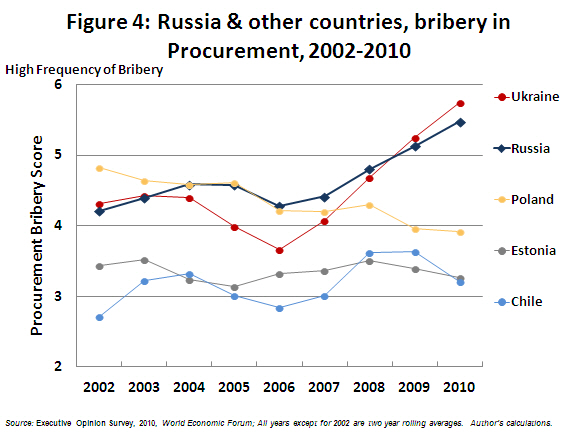

Furthermore, various forms of bribery have risen substantially. The extremely high levels of procurement bribery that pervade today result from an increasing trend over the past decade (figure 4).

Third, the troubling evolution of governance in Russia over the past decade should be a wakeup call for the world, which at times has been naïve about Russia’s and other transitions. Over two decades ago, the Soviet Union collapsed and a democratic era dawned in Russia and many former Soviet states.

But over the past decade the progress in democratic governance has been halting or in some cases reversing in many countries, including Russia.

These developments also carry a warning for the Arab world transition. Just because an old autocratic regime is discarded, the emergence of robust democratic institutions is by no means assured. I have written about this subject in this brief article.

Consider the case of Egypt. The demise of the Mubarak regime may indeed have been salutary, and a necessary precondition for a democratic transition. However, the events being played out also suggest that the dismissal of Mubarak and his government itself was insufficient to produce a robust democracy.

A broader perspective is useful. Of the scores of transitions to democracy that have occurred over the past 50 years, many have not been fully successful, resulting in either stagnation or reversals in democratic governance, as in the case of Russia

Democratic transitions are fragile and require constant vigilance, hard work and democratic institution-building for decades after the initial democratic episode. Short-term setbacks or even marked reversals are not uncommon.

The euphoria of the moment when an old autocratic regime is replaced, coupled with the political expediency of the international community, ought not to blur the analysis of how each transition is or is not progressing.

Yet a frank analysis of the lack of governance progress in a transitioning country ought not to rule out that positive developments may take place in governance-challenged settings such as Russia, Ukraine and Pakistan, or recent entrants to democratic transition in the Arab world.

At times the confluence of political and economic challenges influence positive changes and lead to reforms, and that may be the case in Russia at some point in the future. But progress toward good governance is far from certain in the near term, and would require political courage and the will to reverse recent troubling developments in governance.

1. The recent decline in democratic governance provoked a public rebuke by five European foreign ministers. The critical opinion article about Ukraine’s democratic slide was published yesterday by the New York Times and was written by the foreign ministers of Sweden, Britain, the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany.

Commentary

“Putinsanity”: The Reelection of Russia’s President Should Be a Wakeup Call to the World

March 5, 2012