While unemployment in the United States is declining slowly, millions of Americans still lack jobs and policymakers at the national, state and metro levels are working to find ways to increase job creation and employment. In papers written for the January 13 “Fostering Growth through Innovation” event, William Galston, Gary Burtless, Adam Looney, Alan Berube and Elisabeth Jacobs—examining the persistent problem of unemployment from a range of perspectives—agree that the United States must address the growing mismatch between the skills the marketplace demands and the skills the existing workforce currently has.

The Polarization of the U.S. Employment Market

The Polarization of the U.S. Employment Market

William Galston, Senior Fellow, Governance Studies

Pervasive changes in the structure of the U.S. economy have combined with epochal shifts in the global economy to put pressure on the model of success that has guided the United States since the end of World War II, and American workers have been hit hard.

MIT economist David Autor has traced what he terms the “polarization” of the U.S. employment market. Principally in response to the rapid development of low-cost information technology, both ends of the employment spectrum—high-skill, well-compensated managerial, professional, and technical occupations and low-skill service occupations—have expanded, while medium-skill jobs have declined as a share of the total. The mechanism is straightforward: information technology makes it possible to replace workers performing many routine tasks, whether in the office or on the factory floor, with computerized systems directed by fewer, higher-skilled workers. Two sorts of jobs are exempt from this logic: personal services involving face to face relations between human beings (think aides in nursing homes), and tasks requiring creativity and problem-solving abilities.

International trade and offshoring, Autor shows, are the other great drivers of workforce polarization. “Many of the tasks that are ‘routine’ from an automation perspective are also relatively easy to package as discrete activities that can be accomplished at a distant location by comparatively low-skilled workers for much lower wages,” he says. In short, the combination of information technology and globalization makes it possible either to move routine tasks out of the United States or to eliminate them altogether. And the declining domestic demand for these mid-range jobs means that workers who remain in such occupations are likely to experience a continuing squeeze in compensation.

Although political dysfunction is not the source of these adverse pressures on the U.S. workforce—which millions of Americans feel directly—it largely explains why we have done so little to counter them, much less the many more indirectly perceived trends weakening the American economy. Two linked but distinct political developments are key—the growing polarization between the political parties and the diminished capacity of Congress to address difficult issues.

Read William Galston’s paper »

The Employment Skills Mismatch

The Employment Skills Mismatch

Alan Berube, Senior Fellow and Research Director, Metropolitan Policy Program

At the metropolitan level, workers’ educational levels relative to the demand for education among area occupations mattered for unemployment during the recession. Comparing the average level of educational attainment among a metro area’s working-age adults to the average level of education possessed nationwide by workers in the metro area’s occupations, one study shows that, from 2005 to 2011, metro areas with larger-than-average gaps between education demand and supply had unemployment rates 1.4 percentage points higher than other metro areas. This was similar to average unemployment rate differences over the same period between metro areas with more versus less resilient industries.

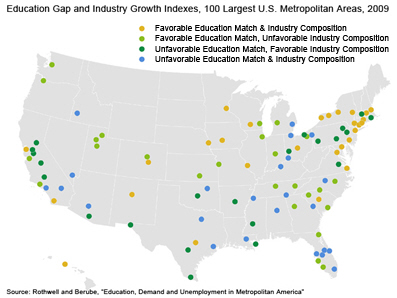

Where might an under-supply of skilled workers be a problem? The map below shows four types of metro areas that either face particular challenges around workforce skills, industry demand, both or neither. The two types of areas exhibiting education gaps include places like Philadelphia, Little Rock, and San Antonio. They escaped the worst of the recession’s effects because of concentrations in relatively stable industries, but may face obstacles to reducing unemployment today because employers’ demand for educated workers may outstrip the local supply. By contrast, places like Augusta, Baton Rouge, Los Angeles and Memphis appear to face a double-whammy–hard-hit industries and a relative lack of educated workers—as they try to reduce unemployment.

These figures do not necessarily contradict the above evidence that skills mismatch explains relatively little of the short-run problems facing the U.S. labor market. In fact, most of what these metropolitan figures may capture is longer-running gaps between worker education and employer demand that contributed to higher-than-average rates of unemployment even before the recession. Overall, a metro area’s education gap explains about half the variation in its average unemployment rate from 2005 to 2010, but just 20 percent of the unemployment increase it experienced from 2007 to 2009.

In this way, the Great Recession shone a bright light on a longer-running issue confronting many major metropolitan labor markets: the need to continuously upgrade the education and skills of the workforce to ensure broadly shared labor market prosperity.

Read Alan Berube’s paper »

Educational Achievement and Employment

Educational Achievement and Employment

Gary Burtless, Senior Fellow, Economic Studies

Adam Looney, Policy Director, The Hamilton Project, and Senior Fellow, Economic Studies

As a result of the continuing shortfall in aggregate demand, joblessness is falling at an unacceptably slow pace from an unacceptably high level. The unemployment rate has exceeded 8% for the past 34 months, a record span in the post-war era. It may not dip below that high level anytime soon. The anemic pace of American job creation means that laid off workers face unprecedented problems finding work. The sharp drop in employment represents a vast waste of human potential. Experience from past recessions suggests that the career interruptions suffered by jobless workers can reduce their potential earnings for a decade or more.

But even before the high rates of unemployment and falling household incomes brought on by the Great Recession, many Americans were struggling in the labor market. In 2007, before the recession began, the median male worker had not seen a noticeable improvement in real wages for more than a generation. Because of stagnant wages among men who work and rising rates of male joblessness, the median 25-to-64-year-old male now earns roughly one-quarter less than his counterpart in 1969. The anemic improvement in median earnings has dramatically slowed the improvement in middle class living standards compared with the early post-war period era.

The challenges workers face over the longer-term have many causes. One of these is technological change, which has allowed machines and computers to take on a growing role in routine production and clerical tasks. Other factors include globalization, which expand the effective worldwide supply of labor that competes with low- and middle-skill U.S. workers. Crucial labor market institutions, such as unions and the minimum wage, have weakened and now provide less protection to workers who have modest skills. A common characteristic of these developments is that they have made the role of skills and education more important in the determination of an individual worker’s wages and employment opportunities.

The evidence suggests that skills and education are increasingly important is reflected in a wide variety of labor market indicators. Workers with the lowest levels of formal schooling have experienced the largest declines in employment and earnings over the past few decades. In the early 1960s the average hourly wage of college graduates was approximately 1.4 times the hourly wage of high school graduates. New evidence on the rising polarization of job opportunities suggests that the growth prospects of different kinds of jobs are diverging, based on job-specific tasks as well as the level of overall skill required to obtain the job. In recent years, advances in information technology and communications methods have significantly increased the demand for the cognitive, decision-making, and interpersonal skills of managers and professionals who are adept at performing abstract, non-routine tasks. The same technical advances have reduced the relative demand for routine clerical, analytical, and mechanical tasks that can now be performed more cheaply with the assistance of machines, such as personal computers, or by poorly paid workers outside the United States.

Technical advance has been less successful in reducing the need for people who perform some of the economy’s least-well paid tasks, many of which require the on-the-spot presence of a manual worker. A variety of low-skill, low-pay, service sector occupations fit this description—health aides, security guards, hospital orderlies, cleaners, and fast food servers. The result has been a long-term rise in the relative demand for very highly skilled workers who can perform abstract, non-routine tasks, comparative stability in the demand for workers with the lowest skills, and a decline in the relative demand for workers with a middle range of skills.

Read Gary Burtless and Adam Looney’s paper »

The German Labor Market

The German Labor Market

Elisabeth Jacobs, Fellow, Economic Studies

In short and simple terms: Germany had effective labor market strategies for weathering the Great Recession because of the incentive structures created by its political economy, which encourages long-view strategic thinking and investments by employers, and the resultant strong and diverse coalition of support for active government labor market policies. The United States does precisely the opposite, encouraging short-view thinking and offering little or fragmented support for active labor market policy.

The “old” German model—highly inflexible labor markets and highly generous social insurance and social welfare policies—was responsible for decades of sclerosis in both the German economy and the German labor market. Yet the American model—extremely flexible labor markets and relatively stingy social insurance and social welfare policies—is arguably responsible for the devastating impact of the economic contraction on the U.S. labor market. Moreover, the American system has generated a highly polarized workforce and remarkably high levels of earnings and income inequality over the last several decades. Based on Germany’s recent economic success in the aftermath of a set of sweeping reforms, it is worth considering whether the Germans have hit upon a “sweet spot” along the continuum of labor flexibility/inflexibility, as well as along the continuum between economic security and promoting opportunity. If this is indeed the case, the question then becomes how to best incentivize this behavior in the United States.

Commentary

The American Workforce and Growth through Innovation

January 17, 2012