In the wake of the killing of Osama bin Laden, a great deal of the debate on Capitol Hill has focused on the efficacy of U.S. aid to Pakistan. Against a background of tight budgets and a broader debate on U.S. foreign aid, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle have voiced varying views. Some have been adamant about freezing and even eliminating aid to Pakistan, while others are staunch in their belief in maintaining support to the country at this critical point in time.

Congressman Ted Poe has sponsored legislation “to prohibit assistance to Pakistan” while Speaker of the House John Boehner asserted that “it’s not a time to back away from Pakistan: it’s time for more engagement with them, not less… aid should continue to Pakistan.” In the Senate, Chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee Dianne Feinstein recently questioned whether the U.S. should continue to provide aid to Pakistan, voicing a clear break with her colleagues, Senators John Kerry and Dick Lugar, who have been stalwart supporters of aid to Pakistan.

Since 2001, the majority of U.S. assistance to Pakistan – more than $20 billion – has gone to Pakistan’s military. Recognizing this imbalance in support, the 2009 legislation introduced by Senators Kerry and Lugar sought to “promote an enhanced strategic partnership with Pakistan and its people” by authorizing $7.5 billion over 5 years in non-military aid for democratic governance, economic freedom, investments in people, particularly women and children, and development in regions affected by conflict and displacement. In addition to being an overt attempt to win “hearts and minds” by focusing on Pakistan’s civilians, the bill also signaled a shift to a more stable allocation of aid to a country that has experienced extreme volatility in U.S. aid levels over the past fifty years as geopolitical interests have shifted.

In principle, the bill sought to transcend the fluctuations of bilateral government relationships to directly serve the “people of Pakistan” through a deeper, broader and longer-term engagement with the country’s citizens.

Reneging on the multi-year pledge of billions of dollars cuts at the very core of the desire to build a relationship with the Pakistani people. Pakistanis are generally very skeptical of U.S. development assistance, believing it to be closely linked with U.S. military interests. The initial controversy over the Kerry-Lugar bill in Pakistan reflects this, as does the increased support for the U.S. following its flood relief assistance. The efforts by the U.S. to help Pakistani flood victims across the country – not just in the Taliban-ridden Federally Administered Tribal Areas – demonstrated to Pakistanis that the U.S. genuinely cares about their well-being separate from its national security priorities. Cutting development aid in response to the news that Osama bin Laden’s long-term hideout was in Pakistan will have the opposite effect.

Maintaining economic assistance to Pakistan, despite the very real concerns the U.S. government has about Pakistan’s military and intelligence services, would be one important way to show Pakistani citizens that the U.S. is serious when it says it cares about their livelihoods. Senator Lindsey Graham and Congressman Jim Moran have suggested useful approaches to moving forward with aid to Pakistan. The former has proposed that aid be cut to those institutions found to have supported bin Laden and Al-Qaeda and the latter has stated that aid to education and economic development be maintained above all else.

Congressman Moran’s proposal to maintain education aid to Pakistan would be well received by Pakistanis, especially if new aid models and streamlined aid processes are utilized to maximize benefits for the country.

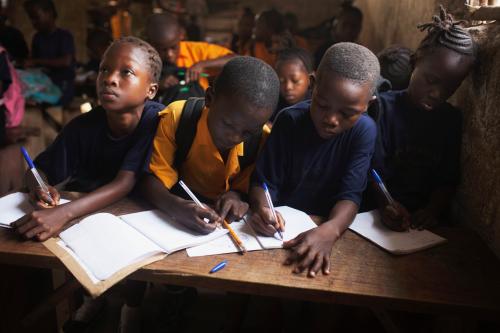

Education is highly valued by Pakistanis, but unfortunately there is a severe shortage of quality learning opportunities in the country, especially for poor rural communities. Girls in these areas are often the worst off. Pakistan ranks as one of the countries with the most out-of-school children. There is huge demand for education from Pakistani children and their parents but one-third of children ages 6-16 cannot read a simple story and only half can write a sentence. Pakistani youth want to acquire the skills needed to enter the workforce, yet one out of every four youth ages 10 to 19 never get inside the classroom.

There are excellent Pakistani civil society organizations that have a proven track record in expanding quality education, particularly for the marginalized. For example, vast improvements in education can be attributed to the work of the Aga Khan Education Services-Pakistan, the Citizens Foundation, and the Children’s Global Network, among others. In just a few years, the Citizens Foundation has quickly scaled up its work to provide quality schooling for over 100,000 poor children from urban slums and rural areas.

The Pakistani government, on the other hand, has demonstrated a more mixed record, often varying by province. In Sindh province, the reform-minded Education Secretary Naheed Durrant was just replaced after only five months on the job after challenging corruption in teacher hiring. Other provincial governments are working much more proactively to make needed reforms.

There is a growing grassroots movement demanding quality education services for all citizens with media companies, such as GEO TV, hoping to increasingly amplify these voices in the future. This demand for education reform can be reinforced by the U.S. government in two ways: first, by directing resources directly to the civil society organizations leading the reform efforts on the ground; and second, by utilizing diplomatic channels to encourage the Pakistani government to incorporate these innovative models into the broader education system.

The citizens of Pakistan deserve a clear message from the United States that it is truly interested in their well-being, including meeting the demand for reforming education. Development assistance to improve education in Pakistan, if done effectively, is one major area that can support and improve the livelihoods of Pakistanis. These core elements of non-military development are where the U.S. government should be investing its resources to establish a stable and long-term relationship with Pakistan.

Commentary

The U.S. Should Maintain Aid to Pakistan, Especially in Education

May 12, 2011