Congressional negotiations continue over the size and contents of the reconciliation spending package and its relationship to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (better known as the bipartisan infrastructure bill).

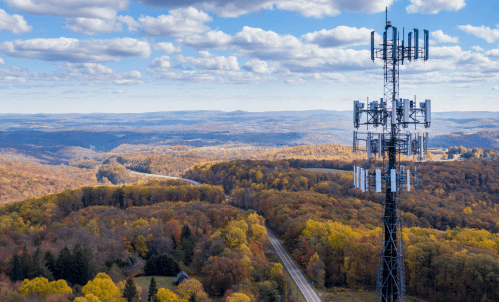

Regardless of when these bills eventually become law and how large they turn out to be, officials in cities, regions, and states look poised to receive a historic level of new federal resources. The potential infusion comes as many are still formulating plans for how to deploy $350 billion in flexible fiscal recovery funds from the American Rescue Plan (ARP), passed in March 2021. The bills now under debate in Washington could layer hundreds of billions of additional federal dollars onto those plans for priorities including transportation, broadband, water, workforce development, affordable housing, clean energy, and climate resilience.

Congress and the Biden-Harris administration have big ambitions for what all this spending will achieve: address the direct impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic; combat income inequality and structural racism; revitalize outdated infrastructure; mitigate climate change; and drive an inclusive and sustainable economic recovery.

That is a bold agenda, and one that leaders in many cities and regions share. But as we argued in a January 2021 Brookings report, the United States risks falling well short of those goals unless local, state, and national leaders organize better to make the most of this historic moment.

Local leaders need to organize regionally

The ARP provided much-needed direct assistance to local and state governments to address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their finances, their economies, their public health systems, and their vulnerable populations. Having used a first round of funds from the Treasury Department to meet many of those needs, many local and state officials are now contemplating a broader rebuilding agenda with a forthcoming second injection of ARP funds. Ideally, those plans will involve more systemic interventions to ensure an inclusive recovery.

As we observed in our earlier report, however, most of those structural issues—inequitable access to educational and economic opportunity, deficits of good-paying jobs, lack of affordable housing, environmental justice—manifest at a multi-jurisdictional, regional scale. With potentially hundreds of billions of additional federal dollars on the way, the case for coordinated regional approaches is only growing stronger.

Yet as with ARP, a large share of spending in the infrastructure bill and reconciliation package will flow through existing channels that leave decisions largely in the hands of state and municipal officials, with only limited incentives or structures to enable regional collaboration. For instance, the reconciliation bill recently approved by the House Budget Committee funds more than a dozen different programs to bolster workforce preparedness, with dollars flowing variously to states, local workforce boards, post-secondary institutions, local school districts, national intermediaries, sector partnership organizations, labor unions, and health care providers (among others). Similar programmatic and jurisdictional fragmentation pervades the bill’s other major spending priorities and those in the infrastructure bill as well.

Regions need a focal point for these efforts that can ensure the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. And the nation, which depends disproportionately on the economic output of its major regions, needs those focal points, too.

Our previous report recommended that local officials in each metro area designate an organization to act as a Regional Recovery Coordinating Council (R2C2). In light of the funding that has already flowed to local and state governments, and the potentially large sums forthcoming, it may make sense for local officials to create more flexible entities—let’s call them “recovery teams”—to advise various implementers on how to aggregate and braid funding around cross-cutting priorities tailored to specific regional strengths and challenges. For some regions, this might include supporting an equitable clean energy transition. Others might focus on improving housing affordability near job or transit centers. If the final reconciliation package preserves substantial investments in free pre-kindergarten and community college, regional and state leaders will have enormous opportunities to build high-performing cradle-to-career systems but will need time and resources to integrate new investment with numerous siloed programs.

Recovery teams could be based within a variety of different regionally oriented organizations: councils of governments, chambers or business leadership groups, community foundations, universities, or other public/private partnerships. Some teams could use competitive programs in ARP (e.g., EDA’s Build Back Better Regional and Good Jobs challenge grants) and the infrastructure/reconciliation bills as foundations for stitching substantial formula grant programs together under a strategic framework. Ideally, recovery teams would specify transparent, quantifiable goals and metrics to guide design and implementation of programs. The teams would be time-limited, however, and focused primarily on getting these efforts off on the right foot.

Regardless of the priorities, forward-thinking local actors—in both urban and rural regions—should consider leveraging the fiscal relief provided under ARP to build regional capacity in anticipation of further resources to come. Treasury guidance specifically permits recipients of ARP fiscal recovery funds to spend those funds on associated administrative costs, and to transfer funds to nonprofit organizations and other units of government. For less prosperous areas with limited local resources, states could make modest allocations to support regional recovery teams. The alternative go-it-alone approach, by contrast, risks not only sacrificing impact, but also overloading already-stressed local government systems.

Federal leaders need to organize cross-functionally

In addition to getting more bang out of their federal bucks, local leaders would also benefit from organizing regionally if doing so facilitated more streamlined interactions with their federal partners. Similarly, leaders in executive agencies charged with implementing these programs would benefit greatly from interacting with central points of contact who are executing on important regional—and national—priorities.

Echoing our earlier report, we recommend the Biden-Harris administration establish a National Recovery Investment Corps (NRIC), a cross-agency staff dedicated to working with regional and state leaders to advance their inclusive recovery priorities. The NRIC could be comprised of officials from within the White House (e.g., National Economic Council, Domestic Policy Council, and Office of Management and Budget) and point people in key agencies such as the Commerce, Education, Health and Human Services, Labor, Transportation, and Treasury departments. The NRIC staff should possess strong knowledge of relevant domestic programs, and experience working with (or within) local governments.

We originally envisioned the NRIC as a vehicle to evaluate formal investment requests from regions, but given significant federal investment already at hand, the NRIC should focus on several other ways it can support regions: flagging relevant funding opportunities; advising on allocating dollars across related programs; gathering and acting on real-time input to inform rulemaking, funding notices, and waiver requests; and serving as a clearinghouse for innovative strategies and monitoring data. The NRIC could encourage regions to formally designate and empower regional recovery teams by dedicating point people to regions that have taken that step. Bruce Katz, Julie Wagner, and Colin Higgins issued a similar recent call for the White House to establish a delivery unit to “take the friction, inefficiency, duplication, and messiness out of implementation and execution.” It might make sense to organize the NRIC around a discrete number of thematic delivery units that mirror key regional and administration priorities, such as the examples noted above.

To make the NRIC a reality, and to support its effective partnership with regional leaders, the federal government needs to redouble its investments in talent. While the NRIC should have seasoned public-sector professionals at the helm, it will also need capable team members committed to supporting local success. And regional recovery teams themselves would benefit from having staff who can liaise continuously with federal partners. Each year, the Office of Personnel Management hires hundreds of recently minted graduate degree holders into two-year Presidential Management Fellowship (PMF) positions. Greatly expanding the PMF program over the next couple of years could add not only much-needed executive branch capacity at this crucial moment, but also deploy talented individuals into regions around the country to ensure unprecedented federal investment serves ambitious national goals.

Building back better will require a different approach

The Biden-Harris administration’s tagline (which is also the working title of the House reconciliation bill) clearly implies that we must improve on the economy that predated the COVID-19 pandemic. For however much investment the administration and its congressional allies secure, the level of ambition and quality of implementation in America’s regions will ultimately dictate whether the benefits of future economic growth and vitality extend to Americans regardless of income, race, or geography. We must organize ourselves differently, both locally and nationally, if we hope to meet that audacious goal.

Commentary

Local and national leaders must organize themselves better to build back better

October 13, 2021