During her unsuccessful 2017 campaign for mayor of St. Louis, Mo., Tishaura Jones wrote a powerful and stinging letter to Tod Robberson, editorial page editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, vowing to “look at every issue through a racial equity lens.” Then the city treasurer, Jones took aim at Robberson’s assertion that “neglect by city leaders” allowed for graffiti and blight. Instead of laying blame on people, Jones pointed to structural inequality.

“What is killing our city is poverty,” Jones wrote. “What is killing our region is a systemic racism that pervades almost every public and private institution.” She promised to “ask if every decision we make helps those who have been disenfranchised, red-lined and flat-out ignored for way too long.”

Jones ran for mayor again in 2021, and was elected this April. Just a few months into her tenure, she is making good on her promises for racial equity. She involved the public in participatory budgeting for decisions on how to spend $68 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds the city received. Within what the mayor’s office calls The People’s Agenda, Jones explains her approach: “Process is policy, and I believe that bringing in diverse perspectives will help us make wise investments and build a diversified portfolio.”

Adding to her progressive bona fides, Jones reallocated $4 million from the police budget by eliminating 98 vacant positions—a move that local Republican officials are seeking to block via the state legislature. And Jones’ commitment to close the Workhouse—the city’s medium-security jail, which community organizers critiqued for years for its substandard living conditions—has led to a sharp dispute among city leaders, which is delaying efforts to pass the city budget for next year.

These kinds of funding battles reveal the ongoing challenges that progressive leaders and activists face in their efforts to help marginalized communities in places marked by pronounced racial inequalities. Jones is right: Black communities in St. Louis are simply not getting needed public investments in critical areas such as school funding and the revitalization of vacant property. The city needs new budget priorities, rather than simply directing more resources into overpolicing and mass incarceration.

Incarceration isn’t an effective economic or community development strategy—nor is it a moral one. Cities can’t arrest families’ talent and breadwinners and then expect to achieve prosperity. Of course, safe streets with resilient homes and thriving businesses are important, in that it’s harder to get the kind of investments that drive economic and social mobility when people don’t feel safe getting to work or school. But as recent research from Philadelphia shows, community development can be a powerful tool for lowering crime while simultaneously increasing communal wealth and neighborhood resiliency.

In this report, we examine the nature of St. Louis’ racial inequalities, with particular attention to the intersection of poverty, incarceration, and educational disparities. We then highlight grassroots, citywide efforts to end mass incarceration and advance equitable development.

St. Louis’ Black residents experience poverty and incarceration at disproportionate rates

As part of her efforts to educate the public on the nature of the problem, Mayor Jones introduced an equity scorecard showing the numbers behind St Louis’ deep racial inequities. For instance, the scorecard shows that the city’s Black residents are more than three times as likely as white residents to live in concentrated poverty (defined as census tract areas where the poverty rate is greater than 40%), and nearly twice as likely to live in areas with low access to healthy food.

One main indicator of neighborhood-level poverty is lack of access to wealth-building opportunities through homeownership. The scorecard reports that there are almost eight times the number of home loan originations per capita in majority-white census tracts than in majority-Black census tracts, and more than nine times as much vacant land and buildings in majority-Black census tracts than in majority-white census tracts.

The racial disparities in financial outcomes can be seen at the individual level as well. St. Louis’ Black residents experience poverty, severe rent burdens, unemployment, and home loan denial at disproportionate rates, and are also less likely to work in high-wage occupations, own a home, or own a business. All of this translates to a large median household income gap, with white residents earning $55,000 annually while Black residents earn only $28,000.

These citywide racial disparities in income and wealth mirror those found statewide. A 2020 article from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reports that:

- Black Missourian households earned 62 cents per dollar of white Missourian income at the median.

- The typical (or median) white household in Missouri had an income of $58,000, whereas the typical Black household had $36,000.

- Over a quarter (26%) of Black Missourians were in poverty in 2018—over twice as high as that for white Missourians (11%).

As with wealth metrics, the city and the state also have parallel disparities in incarceration. Black people represent only 12% of the state’s population but are a staggering 39% of its incarcerated population. Much of this racial disparity is tied to the ongoing legacy of the war on drugs—a federal program explicitly aimed at Black communities that pumped billions of dollars into policing efforts in cities across the country. Today, Black people in Missouri are almost three times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession (which itself accounts for 50% of drug arrests) than white people, according to a 2020 American Civil Liberties Union report.

The story is not much better in the city itself. According to the equity scorecard, St. Louis’ Black residents are four times as likely to be incarcerated than white residents, and four times as likely to be serving probation. Black residents are also subject to more traffic stops and arrests, and Black-majority neighborhoods experience more use-of-force incidents. Black people’s drug use has been criminalized, and that racial bias has led to excessive levels of imprisonment and punitive sentencing practices. Police budgets are a vestige of that discrimination.

Mapping how poverty and incarceration intersect

The disparities in financial outcomes are deeply connected to those found in the justice system, restricting economic mobility and opportunity for Black people. Opportunity Insights’ research on social mobility demonstrates that future life outcomes for adults are deeply rooted in the demographic characteristics of the specific neighborhoods where they grew up. This research is vital for illuminating why the racialized rates of concentrated poverty at the neighborhood level are so damaging for St. Louis’ Black population.

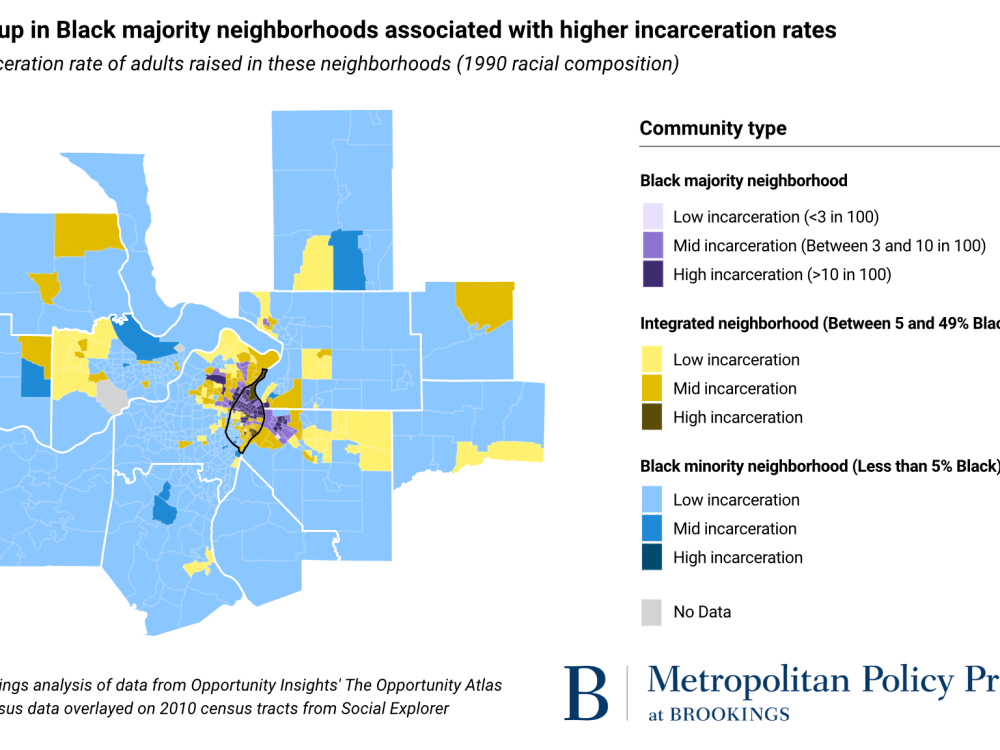

Using Opportunity Insights’ Opportunity Atlas data, we created a map of St. Louis that illustrates how growing up in Black-majority neighborhoods drastically increases the chances of being incarcerated as an adult. Opportunity Atlas tracks a neighborhood’s children into adulthood, with one metric being adult incarceration status. We show the mean outcome of males who grew up in these neighborhoods as the fraction incarcerated on April 1, 2010. We define “low incarceration” as fewer than three in 100, and “high incarceration” as greater than 10 in 100. We define “Black-minority neighborhoods” as neighborhoods with less than 5% Black population, and “integrated neighborhoods” as neighborhoods with between 5% and 49.9% Black population.

This map shows the stunning local variance in incarceration rates based on the neighborhood of where children grow up in the city. While St. Louis has an overall incarceration rate of 4%, some Black-majority neighborhoods have rates as high as 20%; these are places where poverty rates are as high as 56%. The severity of this variance extends to health outcomes, such that ”residents of zip codes separated by only few miles have up to an 18-year difference in life expectancy,” according to a 2015 report.

This map fits with research from Adam Looney and Nicholas Turner, who found that nationwide, those from the poorest quintile are significantly more likely to be incarcerated than those in the middle and top income quintiles.

The connection between poverty and incarceration underscores the importance of Mayor Jones’ belief that “St. Louis must focus on its most vulnerable populations to address core problems first, rather than respond to people’s needs with arrest and incarceration.” But to achieve that vision, the mayor and other elected officials will need to continue to work with grassroots organizers as well as other community leaders, businesses, and philanthropic foundations.

Learning from the grassroots effort to close the Workhouse jail

To pursue equity, it is important to have robust data collection that can help leaders identify disparities. But without decisive action from committed leaders, data alone cannot solve the problems facing St. Louis and other cities. To act on the data, cities need leaders with moral vision on how best to leverage resources and strategies to achieve important goals. Prioritizing budgets to meet Black communities’ needs should include efforts to hear from and invest in the very people who’ve been penalized by biased criminal justice policy. In this section, we highlight on-the-ground activism that has helped shape the equity agenda in St. Louis.

The Close the Workhouse (CTW) campaign, driven by local organizational partners ArchCity Defenders, Action St. Louis, and the Bail Project-St. Louis, has sought to close the infamous jail and reinvest its budget into the community. It reflects years of community organizing efforts leading up to Mayor Jones’ April decision to defund the jail. And while the future of the Workhouse is still uncertain, the campaign to close it provides a good model in local activism.

In an article for the Stanford Social Innovation Review, CTW campaign leader Blake Strode and Amplify Fund director Amy Morris described what their partnership taught them about building trust and sharing power.

Strode is “a proud native son of St. Louis, a queer Black man and a former athlete-turned-litigator-turned-executive director.” His organization, ArchCity Defenders, works with “people seeking to rebuild their lives after being targeted and punished by a criminal legal system of police, courts, and jails in communities struggling to overcome decades of neglect, disinvestment, state violence, and exploitation.”

Morris, in contrast, is a white woman from out of state. Morris leads the Amplify Fund at Neighborhood Funders Group—a “pooled grantmaking fund with twin goals: Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color (BIPOC) should have more power to influence decisions about the places where they live, and philanthropy should have a clear model for equitable development centered in racial justice.”

In the article, Strode explained that finding initial funding sources for the campaign was difficult, both because “CTW’s goals and political frame directly challenge the kind of power and privilege held by philanthropy” and because “funders responded that our initiative was insufficiently ‘measurable’ or ‘practical.’” Fortunately, CTW was the exact type of project that the Amplify Fund was looking to fund. But to be successful, Morris wrote that both she and her organization needed to reckon with the ways that previous white-driven philanthropy from outside the local community “exacerbated negative dynamics between leaders in the region and unknowingly deepened generational, political, and gender divisions between groups.”

The successful partnership between ArchCity Defenders and the Amplify Fund illustrates that great things can happen when outside capital is connected to community insiders who have a stake in the work and who are trusted by their community.

As St. Louis’ local leaders and activists work to build a more equitable city, the CTW campaign can serve as a model for achieving precise goals through coordinated action at the grassroots level. Ultimately, however, these campaigns need to be incorporated into a broader push for equitable development that can mitigate concentrated poverty and provide greater economic opportunity for everyone.

Student debt is holding back equitable development

When it comes to increasing Black wealth, civic leaders often focus narrowly on increasing postsecondary education. This is certainly an important goal, given that education provides social mobility for students born into low-income households or neighborhoods with concentrated poverty. Yet boosting Black postsecondary attainment is an intermediate goal; the larger aim is increasing Black wealth. And that aim is undermined by student debt.

A recent St. Louis city partnership (funded by the Lumina Foundation) between St. Louis Graduates, the St. Louis Regional Chamber, and other organizations provides one example of how to invest in residents by making college more attainable with less debt. This partnership builds on a 2017 Lumina Foundation report that highlighted best practices for schools, including emergency grants and flexible financial aid for low-income students. The partnership also allows for coordination on student advising and degree planning efforts that make degree completion easier. This and similar initiatives designed to improve educational attainment need to explicitly center racial equity, including by addressing racial wage gaps in St. Louis’ labor market, which are present at every level of educational attainment.

Nevertheless, focusing on individual educational attainment alone cannot address the surrounding economic conditions of neighborhoods and communities that are underinvested and consigned to concentrated poverty. In order to address Black wealth as a place-based issue, St. Louis needs a broader vision for economic development.

Recently, Mayor Jones has appointed Neal Richardson, a Black man, as the new executive leader of the St Louis Development Corporation (SLDC), a not-for-profit organization that works to attract private investment and coordinate economic development. In a profile in The St. Louis American, Richardson explained his focus on racial equity as part of a vision for economic justice, saying, “Economic justice is really being able to address the historical barriers and economic inequities that have prevented everyone from being able to contribute, have ownership in our economic future.”

This approach to economic development is a marked improvement on previous approaches, which have focused on adding jobs to the downtown area while simultaneously razing Black-majority neighborhoods in North St. Louis. Richardson’s previous work, by contrast, involved leading an organization that paid minority contractors and students to revitalize vacant property in those same neighborhoods, creating communal wealth by improving underutilized assets.

Richardson explained that to close racial wealth gaps, “we need to have interventions in our policies and procedures,” listing tax incentive allocation and workforce development investment as examples. Interventions will also need to consider the connections between incarceration and mental health and place-based social determinants of physical health. These investments must be directly focused on building wealth, capacity, and opportunity among Black people who’ve been penalized by biased policy.

The stakes are high. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to disproportionately hurt Black Missourians, including those in St. Louis. But even before the pandemic, decades of racial injustice in development left the city’s Black communities and residents locked in intergenerational poverty. Without bold action, cycles of disinvestment, environmental degradation, and lack of opportunity will continue to divide the city and depress the local economy.

But if St. Louis can deliver on the promise of racial equity in its development, it can decrease concentrated poverty, increase citywide opportunity, and add an estimated $14 billion to its regional economic output. The vision Mayor Jones and other leaders are pursuing shows that there is a better way forward for the city.

Commentary

How Black leaders are pursuing racial equity in St. Louis

September 13, 2021