We applaud the Associated Press for their decision on June 19 to update their Stylebook and formally capitalize Black.

In recent weeks, we have seen Black Americans give voice to the injustices and lack of respect they’ve endured since the founding of our country. Millions of non-Black protesters, in cities large and small, have now taken to the streets to amplify those calls for justice and respect.

Yet a simple way to demonstrate that respect—capitalizing the word “Black”—continues to elude many institutions.

While several organizations—including the Brookings Institution—have embraced this change, many arbiters of the written word in the United States have not. The most widely used reference book for media and businesses, the Associated Press Stylebook, tweeted on June 1: “We use lowercase black and white. We know that some people prefer capitalizing Black. We continue to discuss that style.” The 2020 edition of the Associated Press Stylebook, published just last month, does not capitalize Black.

Words matter. And not just for “some people.”

Generally, standard bearers such as the Associated Press cite two primary factors for justifying a writing style change: momentum behind a proposed change and reader comprehension of the revision. To the first point, there is already clear momentum to capitalize Black: Check your inbox and you’ll see statement after statement from executives of companies and organizations using the capital B in their responses to the nation’s protests: Nike, Netflix, Amazon, Google, Starbucks, Target, Macy’s, Nordstrom, Spotify, Apple, Disney, Hulu, HBO, Lyft, Uber, McDonalds, Team USA, Major League Baseball, and Major League Soccer, among many others.

These latest statements of solidarity follow a growing list of media enterprises that have already updated their policies to capitalize Black, including NBC News and MSNBC, TIME, BuzzFeed News, the USA Today Network, Business Insider, HuffPost, McClatchy, Los Angeles Times, Seattle Times, Boston Globe, Chicago Sun-Times, Philadelphia Tribune, Detroit Metro Times, San Diego Union-Tribune, Sacramento Bee, Columbia Journalism Review, as well as The Canadian Press, Toronto Star, Globe and Mail, and CBC News. Black media outlets, such as Essence magazine and theGrio, led the way in capitalizing Black.

The National Association of Black Journalists has formally adopted the policy, noting in a statement, “For the last year, the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) has been integrating the capitalization of the word ‘Black’ into its communications. However, it is equally important that the word is capitalized in news coverage and reporting about Black people, Black communities, Black culture, Black institutions, etc. NABJ’s Board of Directors has adopted this approach, as well as many of our members, and recommends that it be used across the industry.” And that’s nothing to say of the Black scholars who have advocated for the capital B for decades.

This collective momentum toward capitalizing Black also demonstrates growing reader comprehension of the need for the revision. In recent weeks, people across the United States—and indeed the world—have lifted their collective voice to make clear that Black (not black) lives matter to them.

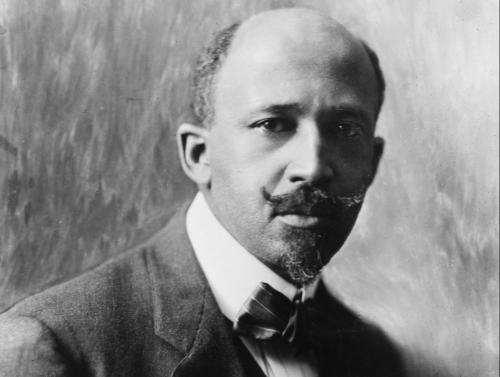

The call to capitalize Black follows a longstanding struggle for Black respect and justice. Almost a century ago, NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois launched a letter-writing campaign to major media outlets demanding that their use of the word “negro” be capitalized, as he found “the use of a small letter for the name of twelve million Americans and two hundred million human beings a personal insult.” Ultimately, The New York Times updated its stylebook to capitalize “Negro,” noting that it was “an act in recognition of racial respect for those who have been generations in the ‘lower case.’” Over time, as “Negro” fell out of favor, the spirit of that change was lost as “black” became the predominant term used to represent this group of people.

More recently, in a 2014 op-ed in The New York Times, Temple University journalism professor Lori L. Tharps had this to say: “When speaking of a culture, ethnicity or group of people, the name should be capitalized. Black with a capital B refers to people of the African diaspora. Lowercase black is simply a color.”

Tharps’s argument highlights the fact that Black people have a common cultural identity of history, art, community, and shared experiences. Most Black Americans lack a specific geographic identity, as they are unable to conclusively trace roots back to a specific country of origin due to enslavement. That lack of shared geography is actually part of what binds Black people together. And while “African American” is a fine terminology choice, it is sometimes considered inadequately representative by Black Americans with recent Caribbean or British lineage, for example, or those who have recently emigrated to the United States from Africa.

Momentum, comprehension, and history clearly support capitalizing “Black.” Some, however, will undoubtedly ask, “But what about capitalizing white?” They will argue that if one racial term deserves capitalization, another should too.

But that thinking is, at best, a false equivalence between different issues. At worst, it’s a deliberate excuse to not address racial injustice, just as “but what about Black on Black crime?” or more recently “but what about looting?” distract from honest attention to systemic racism. To argue “but what about capitalizing white”—particularly without presenting rationale and reasonable articulation on the topic—contributes to the harmful framework and power imbalance that says Black Americans’ progress can only be assessed or measured against white Americans. Giving Black Americans the respect they deserve is not a zero-sum game. The decision to capitalize Black should be made on its own merits.

Complementary assessments of whether other racial or ethnic terminologies should be updated are unquestionably encouraged. However, grammarians’ squabbles over parity cannot tip the scales away from taking action to formally recognize Black people. Otherwise, stalled debates focused on parity will continue to devalue Black society.

Brookings conducted extensive research before making the decision to capitalize Black in 2019, and has continued to have conversations with many dozens of stakeholders on the topic. Like many university or research institutions, we adhere to the Associated Press Stylebook in our writing and publications, but broke with its specific guidance on racial terminology out of respect for the Black community. Today, the call is out for other prominent media and publishing organizations to join in capitalizing Black so that, together, we can demonstrate for the Associated Press and other standard bearers that this change is long overdue and ought to be formalized.

Words, like Black lives, matter. It’s Black, with a capital B.

Commentary

A public letter to the Associated Press: Listen to the nation and capitalize Black.

June 16, 2020