Mark Fisher is Chief Policy Officer and Matt Impink is Director, Policy and Civic Engagement at the Indy Chamber. The Indy Chamber, Brookings, and two other regions are engaged in a six-month project exploring the role of economic development in contributing to better outcomes for workers, firms, and communities.

Earlier this year, the Indianapolis City-County Council voted 17-8 for a 0.25% income tax dedicated to mass transit. This was the final step in a decade-long effort to significantly improve mass transit in Indiana’s state capitol, whose underfunded ‘IndyGo’ transit system struggles to serve the nation’s 14th largest city with an aging bus fleet ranked 83rd by size.

The council vote ratified a 60% victory in a public referendum for transit funding held in last November’s election. It also followed years of planning, public outreach and advocacy on the issue by a broad coalition of public agencies, philanthropic and civic groups, and the business community. (With community partners, the Indy Chamber led the campaign to pass the referendum).

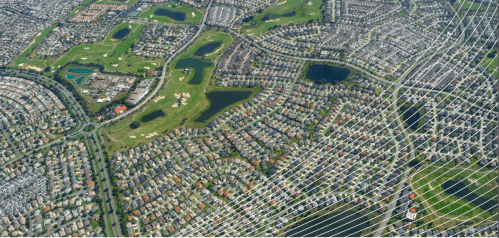

The expansion comes at a critical time for the region. Indianapolis has seen significant investment in tech and advanced industry jobs, while both downtown and suburbs have boomed. But many Indianapolis residents are isolated from the economic opportunities that replaced once-plentiful assembly line jobs in the urban core.

A 2015 Harvard study ranked Indianapolis among the most difficult cities in which to escape poverty and identified limited transportation options as a critical factor. That same year, a Brookings analysis noted that jobs within an average 20-minute commute of Indianapolis’ urban core have shrunk 20% since 2000. At the same time that nearby employment has declined, poverty has grown (80% in the metro since 2000), with 65,000 residents falling below the poverty line in Marion County alone. There’s no simple solution to their plight, but mass transit can help bridge the growing gap between people and jobs.

Over the next 5+ years, IndyGo will make high-frequency bus service accessible within walking distance to triple the population and double the number of jobs. The expansion will modernize the fleet, expand routes and service hours to cut travel times for the typical rider (to make transit a practical option for third-shift and weekend work), and build three new bus rapid transit lines through high-density corridors.

Finally, the plan improves service where it’s needed most, putting 60,000 more people earning poverty-level incomes a half-mile from frequent transit, with 100,000 more jobs a (realistic) bus ride away. Along the proposed bus rapid transit routes, there’s also growing optimism about redevelopment potential in long-neglected neighborhoods.

On a practical level, our member businesses were initially interested in mass transit to increase employee mobility to fill existing jobs, but that interest has broadened as the region rethinks its approach to traditional economic development. The socioeconomic stakes of transit have grown higher in the minds of corporate and civic leaders – and its cost now looks more like an essential investment for the region’s global competitiveness and achieving more inclusive outcomes.

Now, as IndyGo prepares to finally implement its Marion County Transit Plan, expectations are high that an expanded system will be a straightforward investment in both short-term convenience and longer-term upward mobility. By connecting proposed improvements to a broader vision – economic growth, inclusion, competitiveness– Indy is showing that despite the often polarized debate over public investments like mass transit, an aspirational case for progress can – and does – carry the day.

Commentary

The socioeconomic stakes of transit

March 28, 2017