It is rare that an FCC meeting evokes thoughts of “The Little Prince.” Still, reading accounts of last week’s contretemps over Lifeline—a program to promote telecommunications access for low-income households—reminded me of the prince’s observation that “what is essential is invisible to the eye.” The stories focused on the conflict, ignoring the consensus forged and more important, the essential progress made.

The meeting stopped and restarted several times as Commissioner Mignon Clyburn and the two Republicans negotiated over the program’s budget. Eventually Clyburn rejoined the two Democrats and voted for the chairman’s budget proposal. I don’t deny the drama of the cliffhanger negotiations, nor the WWE-worthy accusations of foul play that followed when those negotiations broke down.

The excitement, however, distracts one from the simple truth about the Lifeline budget. Its parameters will be decided by November’s election, not by the five current commissioners. Thursday’s vote was an opening bid but is subject to many adjustments down the line.

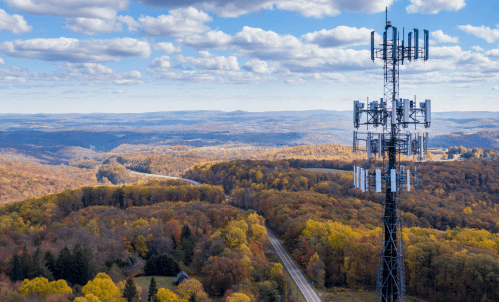

Far more important was the essential and long-lasting structural transition of Lifeline’s voice-centric framework to one reflecting the centrality of broadband. The commission also took steps to transfer the determination of eligibility from the carriers to a third party and remove barriers to more carriers participating. Nothing will do more to improve the value delivered to the intended beneficiaries than robust competition in that market segment.

Unlike on other telecom issues, a consensus has emerged in support of this generational change. Despite the spat between commissioners, it’s truly incredible to see the spectrum of supporting statements from, among many others, A&T and Google, USTelecom, and Free Press, Comcast and former Commissioner Michael Copps. All echoed Copps description of the decision as a “giant leap forward.”

Of course, consensus is not the same as unanimity. States have raised concerns that a national verifier of eligibility will limit the states’ ability to protect the public. I’ve seen many battles between the states and the federal government on telecom issues, from the Hundt Commission preempting state wireless pricing authority through litigation over the 1996 Telecom Act and continuing through today. I have sometimes agreed with the states, but on Lifeline, I think the FCC has the better argument. The key to reducing fraud is reducing incentives to engage in fraud, which the FCC has done by transferring responsibility for verification. Moreover, the best protection for consumers is competition—and the newly-designed lifeline should remove significant barriers to competition among carriers.

Lifeline progress should be particularly welcomed by cities. As a letter from over three dozen mayors supporting reform noted, “Getting more low-income households online will help modernize delivery of public services—facilitating more responsive and effective governance while lowering overheads for local governments. E-government delivery also saves the public the expense of visiting government offices in person—a particular concern for low-income households. Taking advantage of e-government frees public beneficiaries from losing wages if they are paid hourly, and it allows easier and more ubiquitous access to opportunities and resources.”

Some year hence we will forget the heated press conference that followed last week’s meeting (just as future generations, I hope, will forget that 2016 presidential debates featured discussions of men’s hand sizes). Instead, we will see what the mayors envision—modernized public services that take advantage of the digital platform to improve the lives of all, but particularly low-income Americans. If history is fair, we will then remember the essential giant leap the FCC took last week enabling that achievement.

Commentary

FCC makes essential Lifeline progress

April 6, 2016