With its fairly aggressive targets, the Obama administration’s recently announced Clean Power Plan is a supply side approach to curbing the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. The rule gives states broad flexibilities to change their plant performance, including upgrades to plant equipment, transitions to cleaner fuels, or even trading credits with cleaner states. It is also a policy rooted in spatial geography, as the rule will affect states and metro areas in different ways based on their varying reliance on fossil fuels and renewable energy.

But it will take more than supply side techniques to achieve the country’s emissions targets. Equally important is how the country’s energy demands translate into greenhouse gases. And much like the supply side, energy demand is not even across the country. Instead, energy demands from the country’s metro areas have an outsized impact on national emissions.

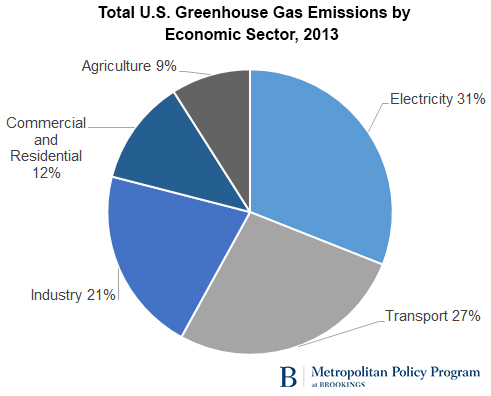

To start, it’s important to explore how economic activity translates into greenhouse gas emissions. The EPA publishes an easy-to-understand pie chart, dividing the economy into five sectors: electricity, transportation, industry, commerce and residential, and agriculture. Each of those sectors can claim a significant share of emissions, but the non-agriculture sectors combine to produce over 90 percent of all emissions. Put another way: Demands from the built environment are the major driver of total emissions.

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

That creates a straight line to the country’s metro areas. Metro areas house the majority of the country’s people and economic activity, and the vast majority of emissions related electricity usage trace back to residential, commercial, and industrial demands. The same goes for the fossil fuels needed to heat and cool buildings in metro areas. Metros also host the majority of vehicle miles driven, transit trips, train and aviation passengers, and freight activity—meaning they’re the locations where fuel gets burned. As a result, metro areas are responsible for the country’s largest aggregate carbon footprints, and they’re massive net importers of fossil fuels.

Fortunately, there are local solutions to address metro areas’ outsized energy demands.

They can begin, and simultaneously improve supply-side emissions, by expanding rooftop solar production. Public policies like net metering and GIS scanning of rooftop potential can all promote solar installations, and in the process replace significant amounts of electricity generated from fossil fuels. Private programs, including Google’s new Project Sunroof, can facilitate that process. Distributed solar poses its own set regulatory questions, but there is no doubt that it can help contribute to a more sustainable energy portfolio and reduce costly energy imports.

Metro areas can also change their physical development patterns, both in terms of geography and the buildings themselves. Denser housing requires less heating and cooling per unit. And until all cars switch to electric power sourced from renewables, greater density can replace automobile trips with walking, biking, and transit. Amended codes for cooling, heating, and lighting equipment and requirements for digital sensors can address building-related emissions. Likewise, programs like the Energy Department’s Commercial Buildings Program and the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED system give developers and tenants the tools to reform their consumption patterns.

But completing this process will require a reformed partnership between metropolitan actors and their state and federal peers. At the state level, that means regulations around buildings and land development patterns, plus innovative programs like green banks to promote clean energy investment. Federally, international agreements and national standards can push metro areas to further improve their emissions while a national carbon fee would use market mechanisms to the same ends.

The Clean Power Plan is a great effort on the supply side—the next step should be policies to address demand.

Commentary

The Clean Power Plan shouldn’t discourage the work needed around energy demand

September 9, 2015