As President Obama and others commemorate lives lost and progress made in New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina, competing narratives about the city’s recovery and its beneficiaries will emerge. Yet, most agree that the work to reinvent New Orleans remains unfinished.

That’s true, especially because post-Katrina New Orleans is trending back toward its old self—a sluggish regional economy with high inequality and not enough opportunities for its residents.

That was certainly not the vision. Mayor Mitch Landrieu often says that Katrina’s “near death experience” forced clarity about the need to rebuild the city and region better and stronger following the storm and the levee breach. And when Brookings launched the Katrina Index 10 years ago (now the New Orleans Index run ably by The Data Center), our goal was to measure not just rebuilding activities but the extent to which the billions of government, philanthropic, and corporate dollars—and citizen sweat equity—were resulting in a more prosperous and sustainable region.

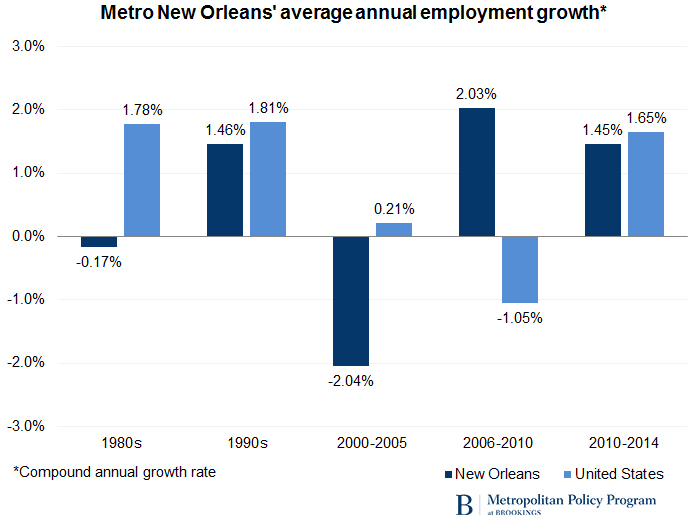

Ten years on, we wanted to know if post-Katrina New Orleans is breaking away from its prior path of economic distress and deep social divides. Is the region steadily improving on metrics of growth, wealth creation, and inclusion since the 1980s, not just measured from the nadirs immediately following Katrina or the recession? If you do the latter, the New Orleans metro area “ranks #1 on job growth,” as boosters will tell you as they cite Brookings data.

What we found is sobering.

First, job growth in metro New Orleans is slowing, and the new jobs are predominantly low-quality. The average annual rate of job growth from 2010-2014 has waned since the years immediately after Katrina with the slowdown of rebuilding activities; it now matches the average rate of growth during the 1990s. Yet, seven out of 10 jobs being added in the metro area have occurred in low-wage industries like tourism, administrative services, and retail. In contrast, job growth in good-paying industries like transportation and distribution, energy and petro-chemicals, and durable manufacturing lags their peers nationally.

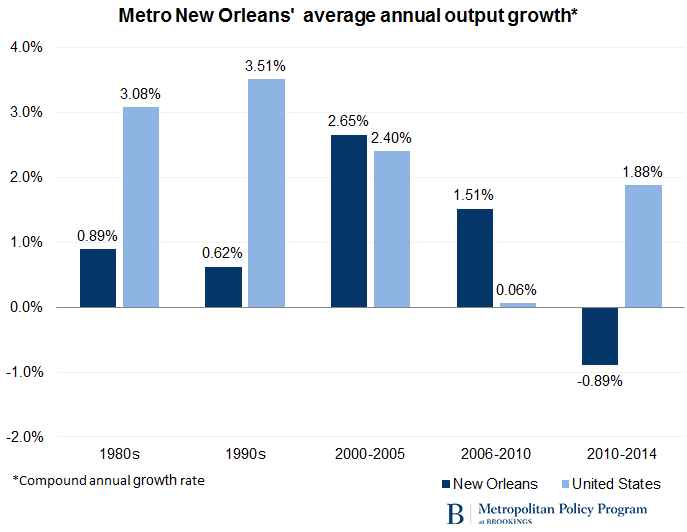

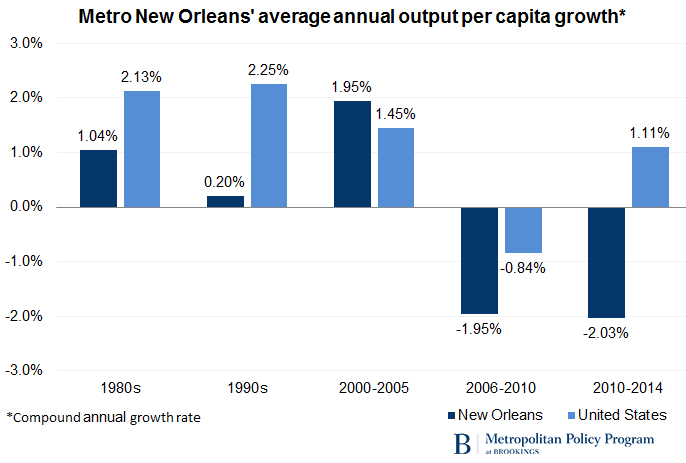

Second, the economy has stalled and is not generating enough income to improve living standards. Output, a standard measure of the value of goods and services being produced in the economy, declined in greater New Orleans by an average of 0.89 percent per year between 2010 and 2014, a worse rate than in the 1980s and 1990s. Output per capita shrank as original residents and newcomers returned to the New Orleans area, a sign that the regional economy lacks capacity to produce higher wages, grow good jobs, or support public services in line with population growth.

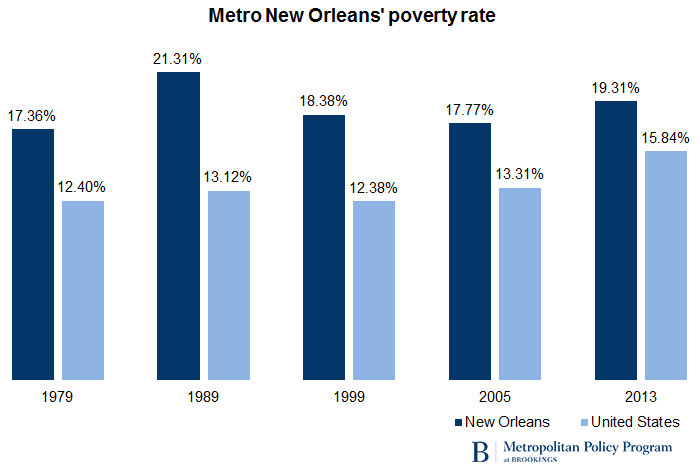

Lastly, metro New Orleans’ sluggish economy has been accompanied by growth in poverty and a decline in median household incomes. The share of the region’s poor climbed to 19.3 percent in 2013, up from 17.4 percent in 1979. Median household income in 2013—at $45,981—is lower in real terms than in 1979. Meanwhile, many white households in greater New Orleans are better off, having expanded their ranks in the middle- and upper-class since 1999 while the corresponding share for black households shrank.

These numbers are a stark reminder that the last 10 years of reforms represent only a down payment on the harder work ahead.

For New Orleans to change economic course, leaders must make diversifying the economy and workforce development top priorities. To date, leaders and citizens have justifiably focused their reforms on fixing the basics—good schools, safe streets, accessible health care, and strong coastal protections from future hurricanes. These are essential to a functioning economy and healthy markets.

Going forward, leaders must adopt bold reforms to lessen the region’s overreliance on tourism and the boom-and-bust oil and gas sectors to increase prosperity. This does not include giving away wasteful film tax credits or reviving a medical corridor that predominantly provides local services. Instead, leaders should cultivate emerging competitive advantages, like water management. They can help existing industries, such as metal manufacturing and insurance and finance, innovate and move up the value chain. As these industries produce good-paying jobs for workers without a college degree, leaders must expand efforts within the k-12 education system, community colleges, and other training programs to prepare and connect low- and mid-skill workers, especially workers of color, to these jobs. And finally, future efforts must be regional. While some of the most exciting reforms have been in the core city, most low-income residents and jobs are in the suburbs.

Putting a region on a better economic trajectory can be done. Louisville, Pittsburgh, and San Diego are cities that experienced dramatic turnarounds as a result of decades of deliberate civic focus and collaboration. Whether prompted by the collapse of manufacturing and steel or over-reliance on military and defense spending, each of these cities and regions are now known as centers of innovation and entrepreneurship in advanced manufacturing, hi-tech robotics, and life sciences, anchored by applied research capability and strong industry partnerships with universities. They also think and act regionally. Louisville not only merged their city and county to unify behind a common economic vision but they are also collaborating with nearby Lexington to solidify shared advanced manufacturing strengths. Their manufacturers, led by Ford, Toyota, and GE Appliances, have forged their own regional collaboration around apprenticeships and workforce training.

After the anniversary frenzy fades, the people of greater New Orleans have the chance to set the next bar for collective action—quality jobs, growing incomes, and better opportunities for every segment of the community. That would be progress from pre-Katrina New Orleans.

This blog post has been updated with an additional graphic, “Metro New Orleans’ average annual output per capita growth.”

Commentary

Post-Katrina New Orleans is bouncing back, but not for the better

August 26, 2015