A year after Ferguson burst into the national consciousness, poor residents in the St. Louis region continue to struggle with entrenched patterns of racial and economic segregation, despite access to a key program designed to help overcome those divisions. As the New York Times recently reported, families with housing choice vouchers—a portable federal housing subsidy—often find that rather than gaining a toehold in safer communities with more jobs and better schools, their housing choices remain limited to racially segregated low-income neighborhoods that may not be much different than where they started.

Research has shown that vouchers significantly reduce homelessness and relieve overcrowding. But when it comes to increasing access to higher opportunity neighborhoods, the Times story underscores the multiple barriers recipients face—from the legacy of exclusionary zoning laws that limit affordable options in opportunity-rich communities, to landlords who refuse vouchers, to rental practices and information gaps that effectively steer voucher holders into minority and lower-income communities.

How pervasive are those challenges? By mapping neighborhood-level data (from 2009 through 2013) on housing choice vouchers in the nation’s major metro areas, we can see some of the gains achieved by subsidized households as well as the program’s limitations.

A growing number of housing choice voucher holders live in the suburbs. Like the family profiled in the Times story, almost half of voucher households (48 percent) in the 100 largest metro areas find housing in the suburbs. That’s a significantly higher share compared to traditional (“fixed”) public housing units, more than two-thirds of which remain concentrated in the urban core. Yet it’s not quite on par with the share of all poor renter families in the suburbs (52 percent), perhaps because of the voucher-specific mobility barriers noted above.

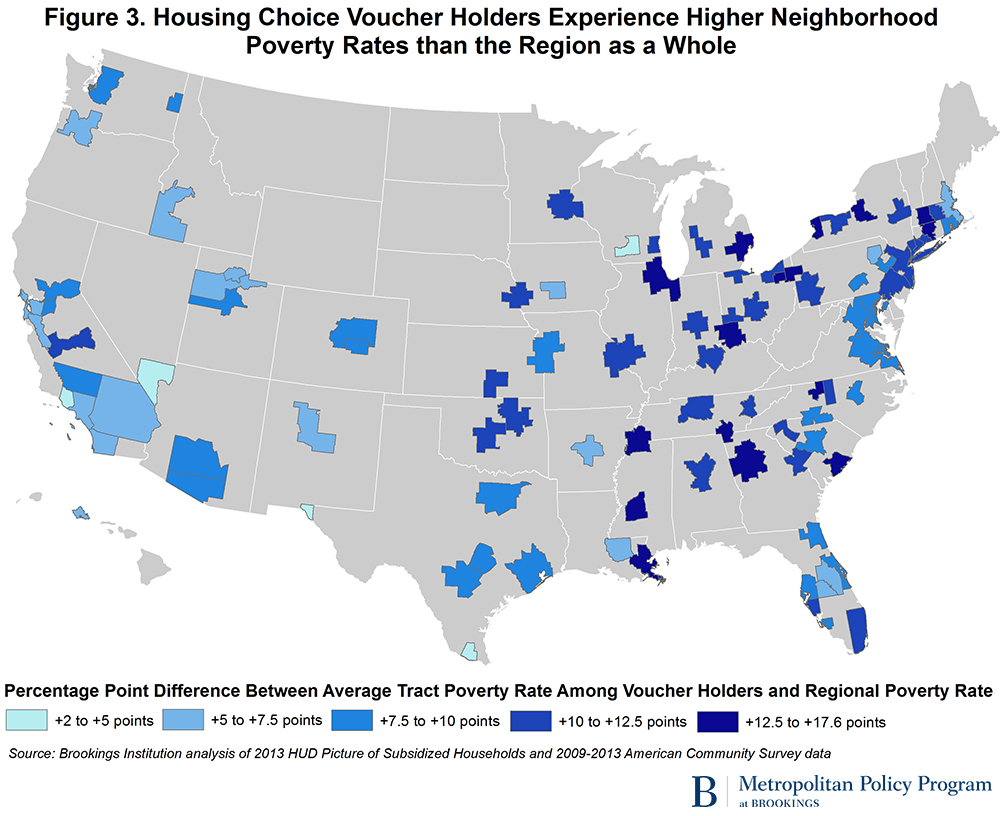

On average, voucher holders live in lower poverty neighborhoods than all poor renters and public housing residents. The typical voucher household in the nation’s largest metro areas lives in a neighborhood with a poverty rate of 24 percent—11 points lower than the average poverty rate for public housing residents and 3 points below the average for all poor families who rent. However, at 20 percent research suggests the negative effects of concentrated poverty begin to emerge. Even in the suburbs, the average rate (19 percent) hovers just under the high-poverty threshold.

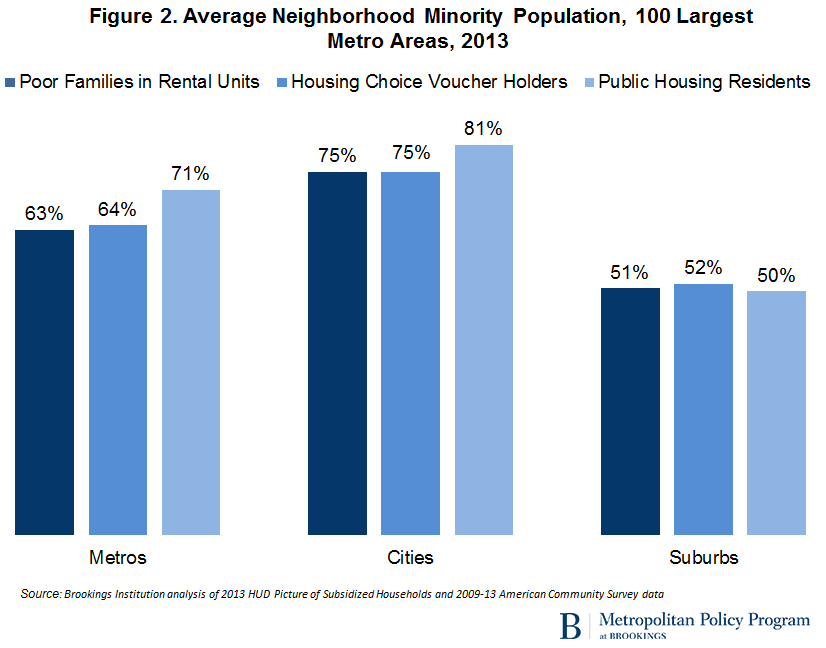

The typical voucher holder lives in a majority-minority neighborhood. Like poor renters overall, a typical urban voucher holder lives in a neighborhood where three-quarters of the population is non-white or Hispanic on average. Even in suburbs, the average neighborhood makeup for voucher holders is still majority minority (52 percent), similar to poor suburban renters and public housing residents.

Voucher recipients’ access to lower-poverty, less-segregated neighborhoods varies dramatically across the nation. Across the 100 largest metro areas, the average voucher holder lives in a neighborhood where the poverty rate is 10 percentage points higher, and non-white population share is 21 percentage points higher, than the average for all neighborhoods. In many Western metro areas, those differentials are much smaller. In Las Vegas, for instance, the average voucher holder lives in a neighborhood with an 18 percent poverty rate (compared to 15 percent region-wide) and where racial and ethnic minorities make up 61 percent of the population (compared to 53 percent region-wide). In older industrial regions of the Northeast, Midwest, and South, those disparities tend to be far wider. St. Louis is one such example; the average voucher holder in that region lives in a neighborhood with a 26 percent poverty rate (compared to 13 percent region-wide) and where 58 percent of residents are racial and ethnic minorities (compared to 25 percent region-wide).

These numbers show that the voucher program has made real, albeit uneven, progress in helping families move to better neighborhoods than they might have otherwise. And research has found that helping poor families move to lower poverty neighborhoods can boost positive outcomes, from improving mental and physical health to helping kids do better in the long run.

But the data also point to the limits of that progress. On average, voucher holders still live in high poverty, less racially integrated neighborhoods. Research has shown that those neighborhoods tend to leave voucher holders with access to poorer performing schools than poor residents overall, and in less jobs-rich areas than their higher-income counterparts. These disparities are most pronounced in regions suffering from longstanding patterns of racial and economic segregation.

Delivering on the potential of the voucher program to improve access to opportunity means grappling with the barriers to mobility that restrict its use. Opening up options in more opportunity-rich areas will require better information for families on where those areas are, steps to ensure that vouchers are truly portable across jurisdictions within regions, and measures that curb landlord discrimination against voucher holders.

Commentary

Promise and pitfalls of housing choice vouchers vary across the nation

August 14, 2015