Earlier this year, the Chinese government released its annual economic report and confirmed fears of an economic slowdown in the world’s second largest economy. For the first time since the 1998 Asian financial crisis, GDP growth missed the government’s target, while registering the lowest rate of growth since 1990, when the country remained under international sanctions following the Tiananmen Square massacre.

Though still well above the global average of 3.3 percent, China’s decline to 7.4 percent annual GDP growth—and fears of future decreases—has roiled the global economy. The International Monetary Fund now expects its growth to dip below 7 percent in 2015 and 2016.

Yet, this misses the story beneath the national numbers. China is likely nearing the limits of its unprecedented growth, as gains from mass urbanization and economic formalization ebb. But its economy is not monolithic and, as the pace of expansion slows, understanding where growth is happening and why is crucial for those both inside and outside China.

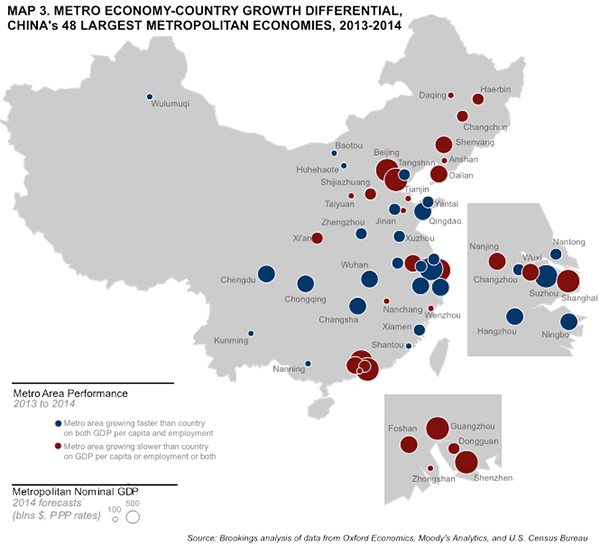

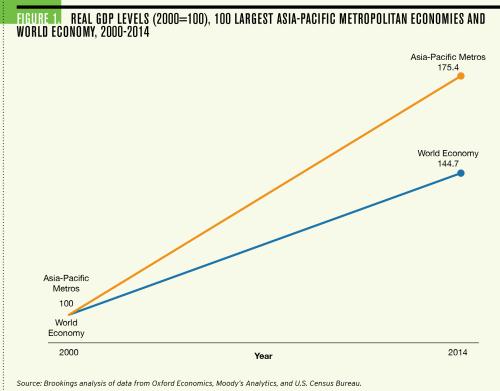

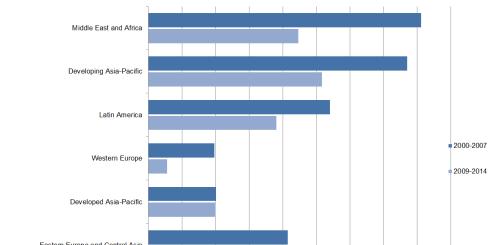

A recent report from the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program and Tsinghua Center offers this ability—tracking the growth patterns of the world’s 300 largest metropolitan economies, including the 48 largest in China. Together, those metro areas are the country’s economic engines—home to 28 percent of the country’s 1.3 billion residents, they generate 56 percent of national GDP. And their economic performance continues to outpace that of the rest of the world: 40 of China’s 48 metropolitan areas are in the top 100 of global economic performance for 2014.

China’s economy is surprisingly distributed across these places. No metro area accounts for more than 4 percent of output. In the United States, New York City alone accounts for over 8 percent.

This economic dispersion is only growing. Among the 48 metropolitan areas, there are distinct pockets of growth—23 metro areas not only outperformed the global average, but also registered both employment and GDP per capita growth rates above the rest of China. These high performers were predominantly smaller economies playing catch-up, while growth in the largest metro areas lagged behind. Indeed, over the past five years, the 10 fastest growing economies have all been from this second-tier of metro economies.

Growth is also shifting geographically from coastal cities to further inland. China’s highest performing mainland metro in 2014 was Kunming, a center of manufacturing and trade in the Southeast that has benefited from government investments to increase connectivity between inland regions, more developed coastal cities, and the rest of Southeast Asia. Similarly, Chongqing, a major metro in central China whose economy is reliant on manufacturing, experienced the largest growth in per capita income, as manufacturers seek cheap labor away from coastal cities. Between just 2000 and 2014, GDP per capita in Chongqing has grown a remarkable 500 percent.

This economic dispersion matters.

For one, the rise of China’s second tier cities is happening as some political power has been devolved (albeit informally) to local officials. As my former colleague Bill Antholis notes, local leaders in China have been given surprising latitude for the last two decades from the central government to pursue economic growth by almost any means. “Local leaders,” Antholis writes, “are increasingly running much of China, from the bottom up.” While Beijing continues to resist true federalism within its political system, de facto federalism will likely continue to spread as the economic clout of its second-tier metro areas grows.

This growth mandate for local leaders is not without negative consequences—from over-building to corruption to environmental degradation. National officials are now focused on that center-local balance—so how provincial and regional leaders are allowed to pursue growth will continue to be critical for the long term success of the economy. Shanghai’s recent abandonment of GDP targets is a promising sign that quality of growth is becoming more important than quantity.

The rise of China’s cities, and their leadership, calls for a city-based economic engagement strategy for U.S. leaders, from the federal to the local level. The potential for city-to-city relationships is particularly strong. It’s increasingly crucial to pursue not merely a “China strategy,” but rather strategies that are targeted at peer metro areas, with similar industries and export opportunities.

Portland, Oregon’s “We Build Green Cities” program —conducted in tandem with the region’s involvement in the Global Cities Initiative, a joint project of Brookings and JPMorgan Chase—exemplifies the approach. Understanding that as developing countries grow more quickly, they will also have to grow more sustainably, leaders in Portland are targeting rapidly expanding cities for exports of sustainable services. This brought them to Changsha, a rapidly growing inland city that has prioritized sustainable development. Over this summer, mayors of the two cities signed a trade partnership that will provide access to “green” services for Changsha, while giving Portland firms a foothold in the challenging Chinese market.

As one member of the Portland Development Commission put it, “Now, when we meet with a firm that has an interest in China, our first thought will be that we have a strong partner in Changsha that can help our firm enter the market.”

Despite its slowing growth, China’s economy is still forecast to surpass the United States sometime in the next decade. Engaging is not a choice; it’s an economic imperative—China’s 48 metro areas already command a GDP of over $5 trillion. Given the right data and strategies, leaders in U.S. cities can begin to build mutually beneficial trading relationships with these places.

Commentary

Beneath China’s GDP Slowdown

March 31, 2015