The new poverty plan unveiled last week by Rep. Paul Ryan has definitely sparked a conversation, generating a flurry of responses from positive to critical to somewhere in between (call it skeptical). By not engaging in a budget cutting exercise as in the past, Ryan has framed his proposals as an effort to start a conversation in Washington about real policy reforms to more effectively fight poverty and promote economic opportunity.

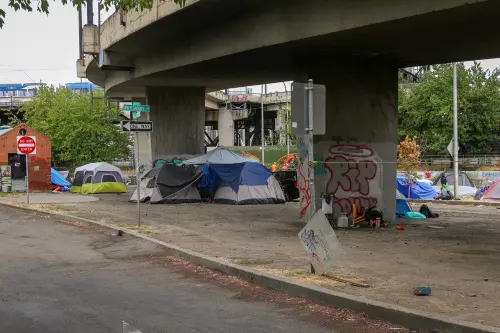

But for all of Rep. Ryan’s talk about the traveling he did over the past year to learn from people fighting poverty on the “front lines,” his new plan says very little about the importance of place in that fight. Whether it’s increasing access to opportunity or streamlining access to services, place matters.

For instance, one proposal that has garnered a great deal of interest is Ryan’s Opportunity Grant. Describing the program in a USA Today op-ed, he noted that, “The problem with all these federal [anti-poverty] programs is that they’re fragmented and formulaic. They don’t see how people’s needs interact.” To overcome this problem, Ryan’s Opportunity Grant would begin as a pilot that would consolidate 11 federal programs into a single block grant. To participate, states would submit plans laying out how they would use those funds on people in need, “hold them accountable” through work requirements, offer choices of providers and track results.

Ryan’s Opportunity Grant tackles a very real problem.

In our work on suburban poverty, time and again we have seen communities trying to craft more scaled, integrated and outcome-driven solutions to confront growing suburban poverty, only to be stymied by a fragmented and inflexible federal anti-poverty policy framework. Not only has the system failed to respond to today’s shifting geography of poverty, it has often impeded more efficient and effective strategies to address poverty in struggling communities.

In some ways, Ryan’s Opportunity Grant pilot is similar to the Metropolitan Opportunity Challenge Alan Berube and I proposed in Confronting Suburban Poverty in America to address these challenges. Both proposals aim to provide greater flexibility and integration to federal funding streams and to use evaluation to figure out and build on what works. However, our Metropolitan Opportunity Challenge would require states to partner with metropolitan and local leaders to target funds strategically within and across regions in ways that measurably increase access to opportunity.

Because Ryan’s plan stops with states it misses the chance to ensure that reforms to the federal system translate into better implementation. It ignores the reality that access to opportunity varies depending on where you live. Different regional labor markets offer different types of jobs, and not all pay wages that offer a path out of poverty. Those jobs that do aren’t spread evenly across places, and may not be accessible to low-income workers who can’t afford to live nearby or maintain a reliable car to make a long commute. Even his proposal of an integrated caseworker and a one-stop-shop for services overlooks the fact that many communities, particularly in the suburbs and in rural areas, lack access to safety net services to begin with.

Many commentators have voiced concerns about the structure of the Opportunity Grant (including the pitfalls of block granting and the challenges of getting outcome measurement right) and about Ryan’s plan more broadly. Hopefully these are the opening salvos of a real debate in Washington about how to fight poverty more effectively in this country. But to make real strides in improving opportunity in America, that debate should be grounded in the understanding that place matters.

Commentary

Place and the Paul Ryan Poverty Plan

July 29, 2014