Bill Baer served as Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice from 2013 to 2016, and as Director of the Bureau of Competition at the Federal Trade Commission from 1995 to 1999.

As the dust settles on the much-anticipated House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee hearing with the CEOs of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google, it’s time to consider what happens next. Those expecting swift new developments probably should curb their expectations. Wheels will turn—but slowly.

In the next few weeks, we likely will see a report from the Subcommittee on its deep dive into allegations of antitrust misconduct by each of the firms. At the hearing, legislators outlined different concerns about the companies: from the way Amazon treats third-party sellers on its platform and Apple handles its App Store developers to whether Facebook’s acquisitions stifle competition and Google’s search protocols advantage its own products. We can expect the report to detail the evidence for these allegations. That will include a review of company documents provided to the Subcommittee and a discussion of interviews with company officials and third parties about specific behaviors, policies, and acquisitions. We also will see an assessment of the adequacy of each CEO’s response to questions posed at the hearing, including areas where the executives dodged relevant questions or even acknowledged possible wrongdoing.

But the recommendations of the Subcommittee will merit close scrutiny too. Will the report urge specific actions for government enforcers at the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice and at the Federal Trade Commission? Will it recommend legislation to change federal antitrust law to facilitate challenging dominant firms that allegedly limit competition in order to lock-in their market power? Will there be bipartisan support for any of the proposed recommendations?

That last question is interesting on its own. While the Subcommittee’s inquiry has been characterized by its members as bipartisan, the CEO hearing revealed significant party differences. Most Democratic members questioned the witnesses about behaviors and acquisitions that they saw as consolidating economic power, while Republicans focused more on allegations of conservative bias across platforms, especially Facebook. How much those partisan differences ultimately matter will depend largely on whether the results of the upcoming election maintain divided party control of the House and Senate or put one party in control of the presidency and both chambers of Congress.

In the meantime, attention will shift to federal antitrust enforcers and some state capitols. The federal enforcement situation is unprecedented—with four high-tech monopolization investigations underway at the same time. These investigations have a couple of things in common: allegations of unfair restrictions on competition by a technology firm with a large share in one or more markets; and concern regarding acquisitions of small firms by the tech giants, as evidenced by the FTC’s sweeping investigation announced earlier this year into the history of and motivations underlying prior acquisitions by these four companies and by Microsoft. But the specific allegations leveled against the four differ:

- DOJ and several state attorneys general are inquiring into Google’s market power in online advertising, and also in search and Android;

- The FTC is looking at Facebook’s prior acquisitions of potential competitors—such as Instagram and WhatsApp. There also is a thinly reported companion DOJ investigation into Facebook’s position in the social media market;

- There are coordinated inquiries by the FTC and the New York and California attorneys general into allegations that Amazon maintains its dominant position as an online marketplace by disadvantaging certain sellers, especially those who offer products that compete with Amazon’s growing list of homegrown offerings;

- Most recently, news outlets report that Apple is under investigation by DOJ in connection with its App Store policies, which include up to 30 percent commissions on sales and restrictions on sharing customer data with app developers.

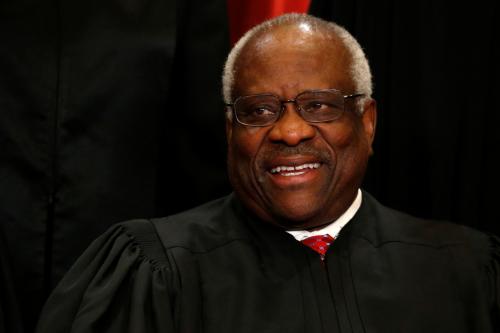

At this point, we don’t know much about the status of these investigations or the likelihood and timing of any subsequent lawsuits, except for the Google case. There, the usually buttoned-up DOJ has suggested some sort of action is imminent, likely before the election. Whether politics underlies that timing and the unusual public statements about a pending nonpublic investigation is hard to discern. But it is unusual that this investigation is led by the Deputy Attorney General, presumably in part due to the belated determination by DOJ leadership that the current Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust ought not be running an inquiry into his former client.

If the Google investigation results in an antitrust complaint, we will learn a lot about what specific behaviors DOJ believe to be anticompetitive and what evidence constitutes proof of misbehavior. But expect a long and drawn-out process. Google and any other charged company will vigorously deny any charges. And the law on what constitutes unlawful monopolization has grown more cautious in recent years, which makes both timing and outcomes uncertain.

We learned that lesson 20 years ago from the biggest monopolization case brought by U.S. antitrust enforcers in the modern era. That was DOJ’s 1998 complaint—after a multi-year investigation—alleging that Microsoft had unlawfully worked to maintain its operating system’s dominance by disadvantaging rivals. It took two years for a district court to announce a decision on liability, a little longer for the district court to order a “break-up” of Microsoft, and another year for the appeals court to agree that the company had indeed behaved unlawfully but disagree about the break-up remedy. In 2001, the case was remanded to the district court where an intervening event—called a presidential election—had produced a new DOJ, a different attitude towards the case and, eventually, a settlement announced some three and a half years after the case was filed.

There is no reason to expect that antitrust actions against Google or others will move more rapidly than that one did, or that the courts will be sympathetic to a monopolization case. Indeed, in responding to the Subcommittee’s request for my views on the need for changes to our antitrust laws, I opined that antitrust jurisprudence has become way too cautious and worried about the risk of overenforcement, with the result that behavior causing harm to consumers is going unaddressed. So, to the extent that harmful business practices limit competition in our economy, we may see justice—but it will be justice after a lengthy delay.

Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft are general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the author and not influenced by any donation.

Commentary

The tech antitrust hearings are over: What’s next for enforcement?

August 11, 2020