Every so often an academic finding gets into the political bloodstream. A leading example is “The Great Gatsby Curve,” describing an inverse relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility. Born in 2011, the Curve has attracted plaudits and opprobrium in almost equal measure. Over the next couple of weeks, Social Mobility Memos is airing opinions from both sides of the argument (see previous posts here).

There is a serious empirical argument over the Great Gatsby relationship between inequality and mobility, as previous posts in this series show. I want to address a different question: why should there be a relationship between the two?

Rungs on the ladder, too far apart

Here’s my hypothesis. When the rungs of the income ladder get too far apart, it is harder to climb. If the ladder had no rungs at all—in other words were there perfect income equality—there would be nowhere to climb and nothing to worry about: an egalitarian’s utopia. At the other extreme, if the rungs were miles apart, only a giant could climb above the clouds. In the US the ladder is still scalable, but we are arguably beyond the point where the incentive the rungs provide to get ahead outweighs the difficulty of the climb.

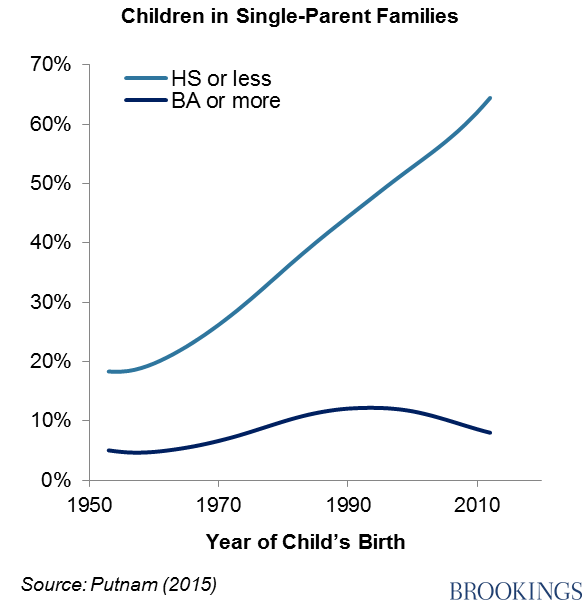

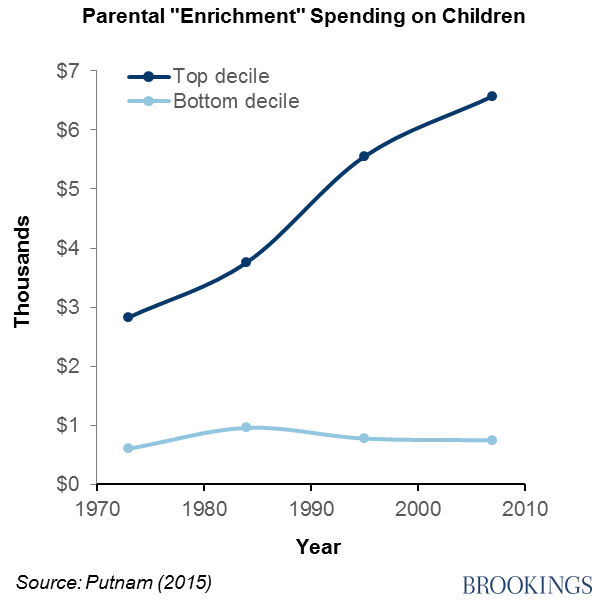

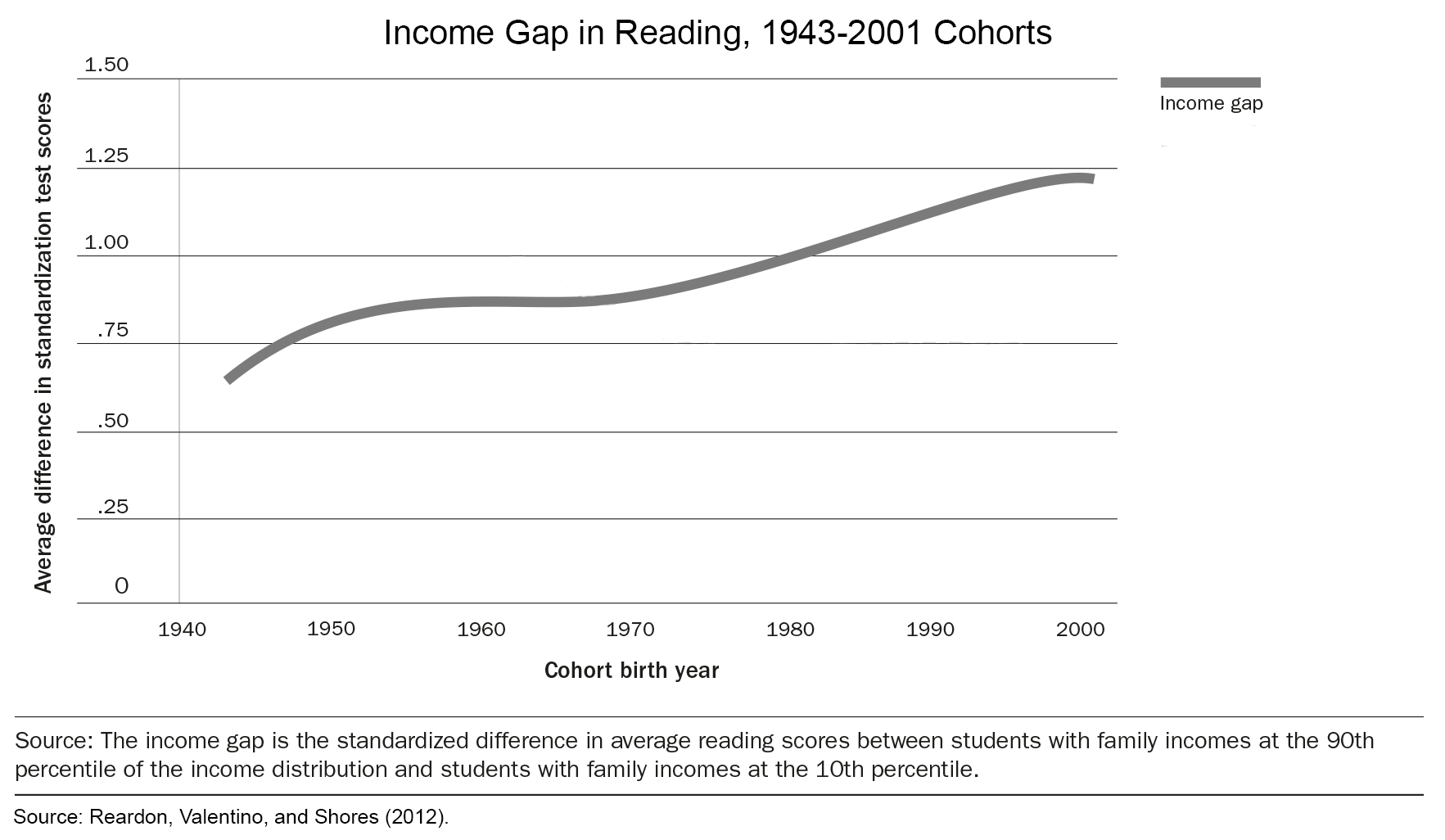

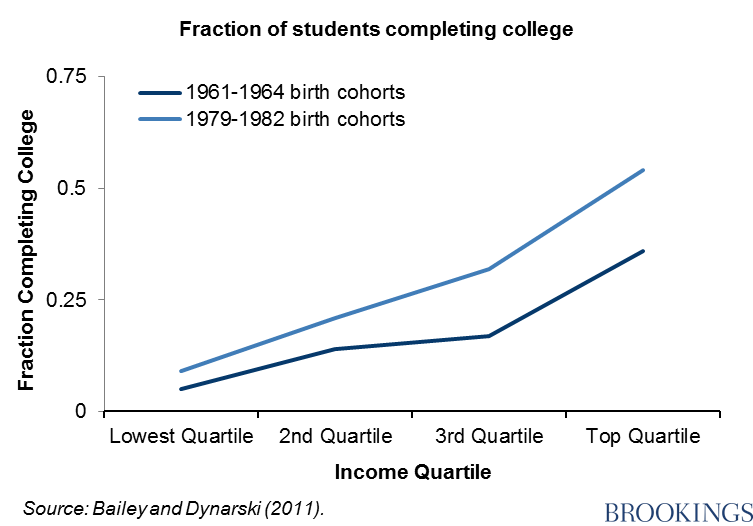

The rungs are not only widening in terms of income inequality. There are growing class-related gaps in family structure, parenting styles, school test scores, college attendance and graduation, and neighborhood conditions. Much of the evidence can be found in a series of “scissor charts” in Robert Putnam’s book, Our Kids. One thing is quite clear: whatever the gaps in an earlier generation between kids from more and less advantaged families, they are much wider now:

We may not have seen a decline in intergenerational mobility in recent decades—but that is likely to be because the kids in the scissors stories have not yet grown up, as Alan Kreuger points out. By the time they are old enough for us to see what impact these growing gaps have had on their mobility, it will be too late to intervene in a way that might help them climb the ladder.

Policy can boost mobility

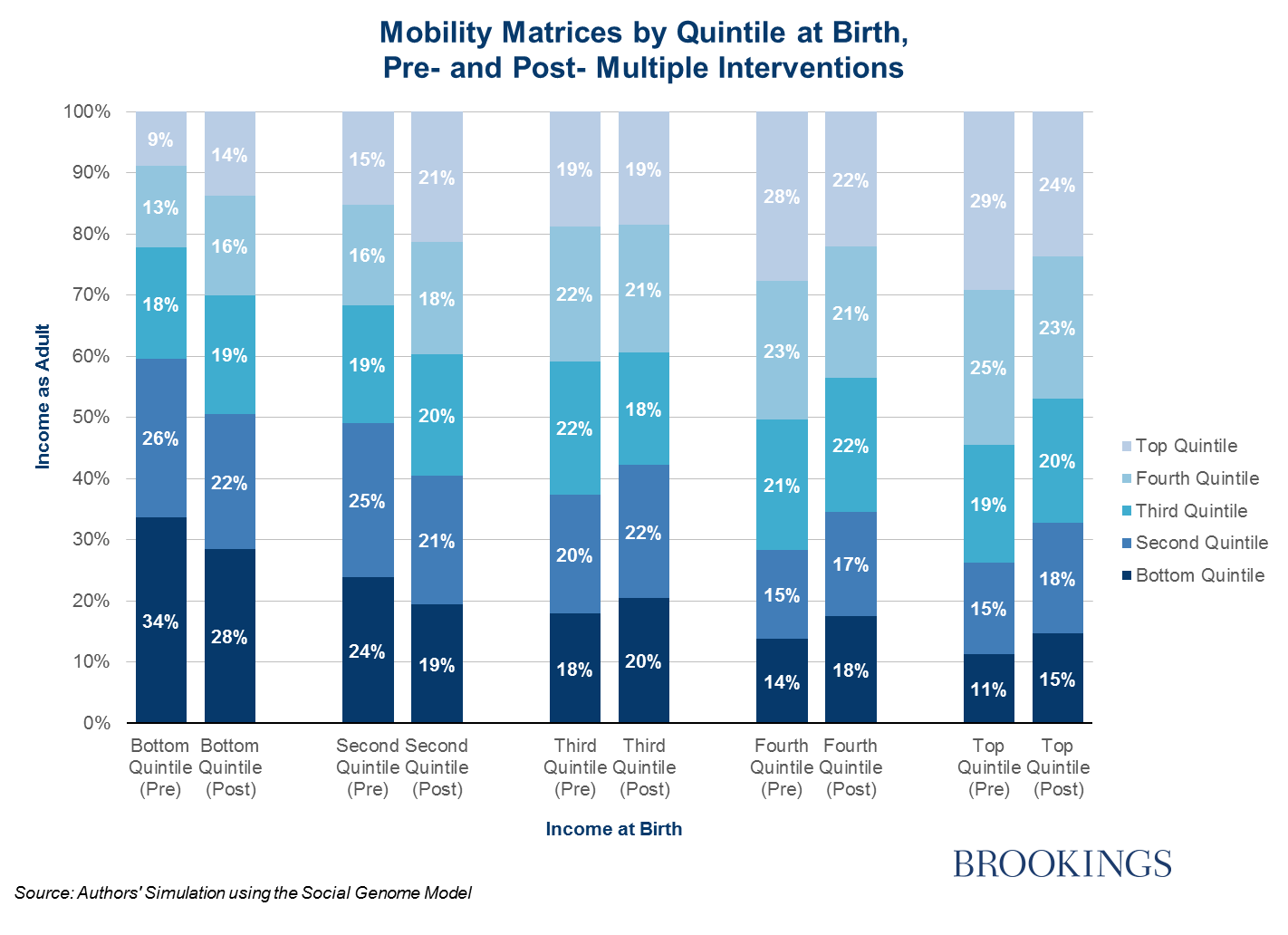

So, what can we do? We should invest in evidence-based programs, starting before birth and extending through high school and the college years. If we provided an effective home visiting program, high quality pre-k, and comprehensive school reforms in elementary and high school, it would make a difference in children’s lives, according to rigorous experimental evidence. Our work with the Social Genome Model suggests that if these programs were taken to scale, one might get a substantial boost to social mobility:

Children born into the bottom quintile would have a much greater chance of moving up if we invested early and often in their skills and opportunities. Before the interventions, only 40 percent move into one of the top three quintiles. Afterwards, almost half do.

These figures should be seen as illustrative rather than precise: but they show clearly that if we work hard to narrow gaps in the early years and beyond, we can improve social mobility: which is surely one of our most urgent challenges as a nation.

Commentary

Inequality and social mobility: Be afraid

May 27, 2015