Making friends with people from different neighborhoods or of different ethnicities protects against a cramped, narrow view of the world, but it could protect against poverty too, suggests a new report from the UK.

Social networks and poverty

Using data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, Understanding Society, a team of researchers supported by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation explored the relationship between social networks and poverty across ethnicities. Their study revealed two important findings:

- White Britons are the least likely to have ethnically and geographically mixed social networks. Only about 40 percent report having a friend of a different ethnicity, compared to 70 to 90 percent for people from an ethnic minority. White ethnic groups are also less likely than most to report having a friend from a different neighborhood, although Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic groups are least likely—nearly 20 percent reported having no friends from outside of their neighborhood.

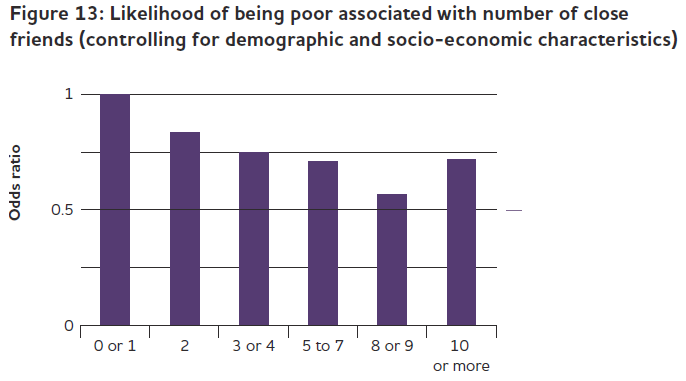

- Socially isolated individuals are more likely to be in poverty than those with larger circles of friends. In particular, those with two or more “close” friends are almost 20 percent less likely to be poor:

Why social networks matter

Social networks are only one mechanism for reducing poverty, and by no means the most direct. It is also inevitably difficult to tease out cause and effect. But the UK results are consistent with the culture of social isolation commonly associated with poverty and social immobility.

Robert Putnam’s new book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis highlights class differences in social ties as one way in which “more affluent, educate families amplify their other assets in helping to assure that their kids have richer opportunities.” Putnam finds a gap in friendship networks between people of differing levels of education. Indeed, the isolation of the most disadvantaged adolescents is a major theme of his book. A number of factors may be associated with this gap, including increased neighborhood sorting by income in the U.S. may be reducing the chances of more diverse social networks, including among children and young people. As he puts it: “Our kids are increasingly growing up with kids like them who have parents like us.” This represents, he warns, “an incipient class apartheid.”

Social networks reflect and reinforce gaps in other domains. As the UK researchers point out: “Social networks cannot be viewed in isolation; broader inequalities, including in education and employment, shape the networks that people have access to and also have a greater independent effect on levels of poverty.”

Opportunity is most threatened when inequality in one dimension strongly overlaps with inequality in others: when lack of income, poor health, low education, and family instability are tightly correlated at the individual or community level. There is another disadvantage to add to the list: isolation.

Commentary

Poverty, isolation, and opportunity

March 31, 2015