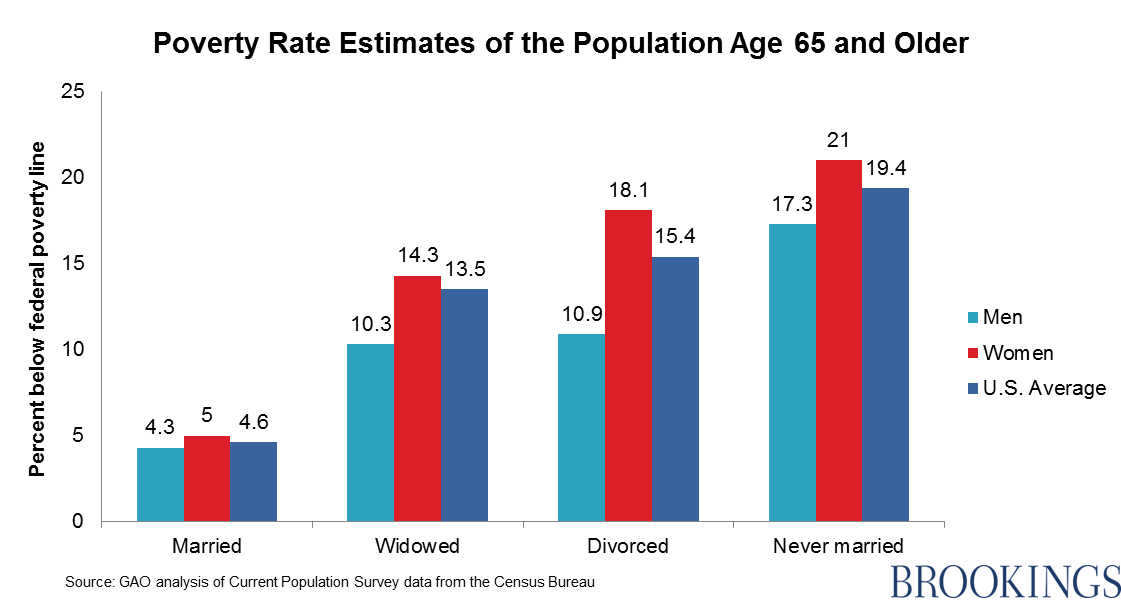

Social mobility is often thought of as a challenge facing children and working-age adults, but sharp drops in income are a real threat for millions of elderly Americans. Widowhood and divorce are often the culprits behind this downward intragenerational mobility—especially for women. The 2012 elderly poverty rate for widowed and divorced women was nearly three times that for married women and the elderly poverty rate for divorced women stood at nearly twice that for divorced men.

Losing a Husband, Then Losing Benefits

Two facts help to explain this risk: men earn more, but women live longer. Higher lifetime wages for men, and the associated retirement assets and benefits, mean that divorce is more of a poverty risk factor for women than for men. Longer life expectancy can also disproportionately impact women who spend down family assets to care for a sick husband or who find their household retirement benefits cut when their spouse dies.

Declining marriage rates have of course reduced the risk of widowhood or divorce, but also reduced women’s access to benefits in the first place. More women are entering retirement without any claim on their spouses’ Social Security benefits—marriages must last ten years for a spouse to qualify. Between 1990 and 2009, the share of 50–59 year old women who were never married for more than a decade more than doubled from 7.5 percent to 16.2 percent. Among African-American women, the share skyrocketed from 13.4 percent to 33.9 percent.

Working Women Do Better

While marriage patterns have hurt women’s retirement incomes, their increased labor force participation and higher wages have been a positive factor. Since 1970, labor force participation rates for married women rose from 40.5 percent to 61.0 percent, approaching those for single men and women. Women are also taking less time off of work to provide care to children or elderly parents. As a consequence, women are now more likely to qualify for Social Security or private-sector retirement benefits in their own right, rather than through a husband.

These countervailing marriage and labor force trends have impacted demographic groups differently. Women with more education and subsequently higher wages will be better off, as their retirement security will be secured by their own income and assets regardless of divorce or the death of a spouse. But women with less education and lower wages, who perhaps would have been married for longer than a decade in the past, may now see their hopes of a poverty-free retirement evaporate.

Public policies can help. A start would be to provide caregivers with Social Security credit and allow them to make contributions to IRAs. Establishing better access to retirement saving accounts, through mechanisms like the Auto IRA, would also help boost saving for the millions of American women without access to employer-based accounts. And policies to encourage a stronger annuity market could help to offset the pain of reductions in the prevalence of defined-benefit plans. Otherwise too many American women will continue to be at risk of falling down the income ladder in the final years of their life.

Commentary

Retired Women at Risk for Downward Income Mobility

October 9, 2014