Hopefully you’ve had a chance to read our new Brookings Essay, Saving Horatio Alger. If not, we bet you’ve found three minutes to check out our new video, using Lego bricks to illustrate America’s mobility challenge:

But readers of Social Mobility Memos want something more: you want to know about the data. Where is it from? How do we slice it?

Making the Matrices

In both the video and the essay, we’ve created a series of ‘mobility matrices’ showing how income status in one generation influences income status in the next. We used a dataset constructed from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ surveys, the ‘National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979’ (NLSY79) and the ‘Children of the NLSY79’ (C-NLSY). Mostly, we use the CNLSY, which provides rich data on children born mainly in the 1980s and 90s. But since they are not old enough for us to know their incomes at the age of 40, we impute adult values using the sample from the earlier generation, the NLSY79. (For more information on how we impute these values, see the Guide to the Brookings Social Genome Model by Scott Winship and Stephanie Owen.)

Other Ways of Measuring Mobility

We chose to use C-NLSY and NLSY79 because it allowed us to keep the data set consistent across our three types of matrices presented (race, education, and marital status). But there are alternatives of course. Another dataset often used is the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (PSID). This started in 1968, so more of the children of the original respondents have reached adulthood. Papers on mobility from Pew’s Economic Mobility Project have used both NLSY and PSID. Others have created synthetic data sets from Census data.

Mobility and Marital Status: A Closer Look

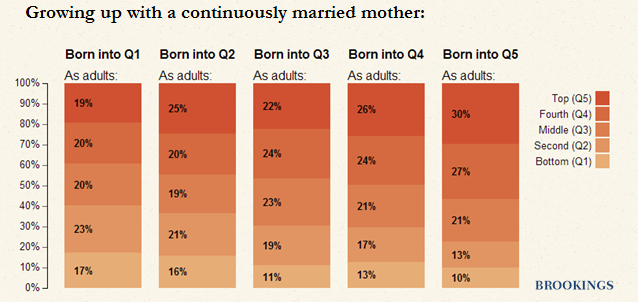

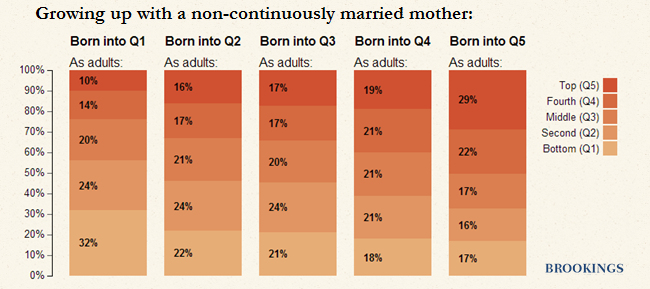

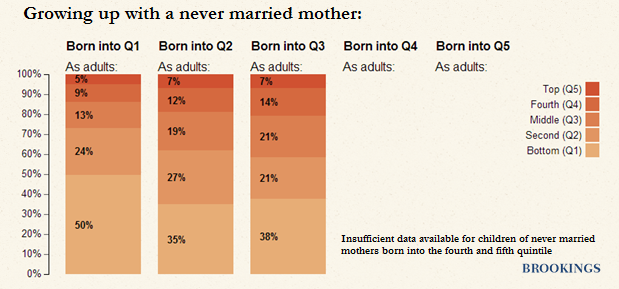

Family structure can have a lasting impact on a child’s life trajectory. Of our sample of 5,783 children, 75% were born to married mothers, 19% to single mothers, and 6% to cohabiting mothers. What counts, however, is not just whether parents are married when a child is born, but the stability of caring relationships throughout childhood. Many unmarried mothers get married; many married mothers get divorced. So we compare outcomes for children raised by mothers in one of three categories:

-

- Never Married: mothers who were unmarried at all four stages of childhood— birth, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence. (This group makes up 11% of our sample).

-

- Not Continuously Married: when the mother reports being married in at least one but not all of the four stages (39%)

-

- Continuously married: when the mother is married in all four stages (50%)

The mobility patterns for the three groups are very different, as you can see below (or in interactive form in the Essay itself):

It is not necessarily marriage in itself that matters for mobility – married parents differ from single parents in many more ways than just relationship status. But these matrices do offer a descriptive look at how family structure during childhood is related to future outcomes.

Commentary

Saving Horatio Alger: The Data Behind the Words (and the Lego Bricks)

August 21, 2014