To say that K-12 education is important for social mobility is to state the obvious. Knowledge and skills give individuals the power to shape their own lives and make their own way in the world. Gaps in the acquisition of skills during childhood and adolescence—some of which appear to be growing—prefigure gaps in adult outcomes.

We’ve rarely tackled K-12 education on this blog, for two reasons. First, too much pressure is sometimes put on formal education to compensate for inequalities of income, wealth, class, neighborhood, race, family structure and social capital. Schools cannot single-handedly cure society’s ills, including lack of upward mobility.

Second, Brookings has an elite corps of education experts over at the Brown Center – very often we can simply point to their work, such as this latest piece from Russ Whitehurst on the future of accountability and standards movement.

One person always worth listening to on education is Michael Barber, the man who brought “deliverology”—the use of metrics and tight accountability frameworks—into the heart of the UK government. In a speech last week to the UK’s Education Reform Conference, Barber made two important points:

Central Government Can Make Bad Schools OK, but Not Good Schools Great

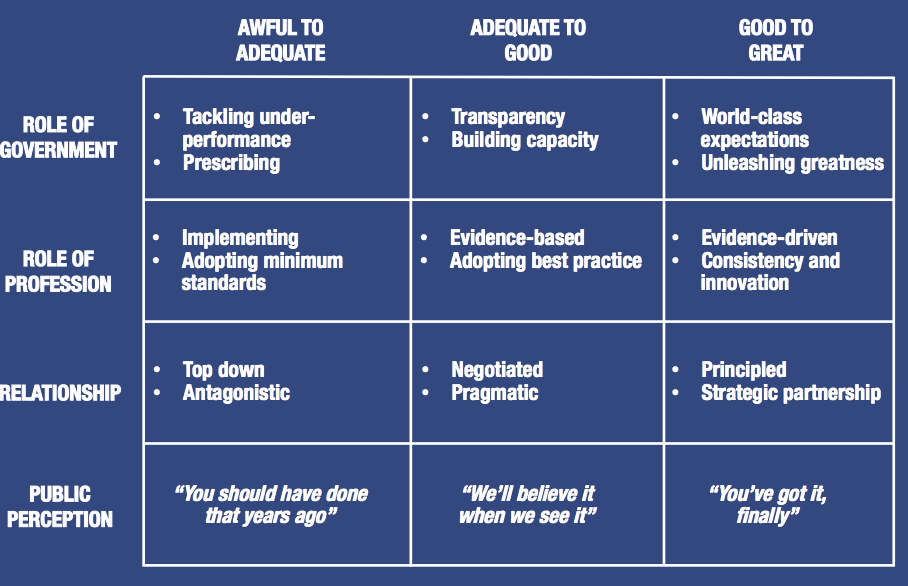

Barber made an important distinction between the policy frameworks needed to get schools from “awful to adequate,” from “adequate to good,” and from “good to great.” His central message: muscular government oversight is needed to lift school performance up from the bottom. But the same approach will stymie efforts to move from good to great, which requires autonomy, leadership and excellence at the school level. Here’s a slide from Barber’s presentation:

Autonomy Does Not Mean Amateurism

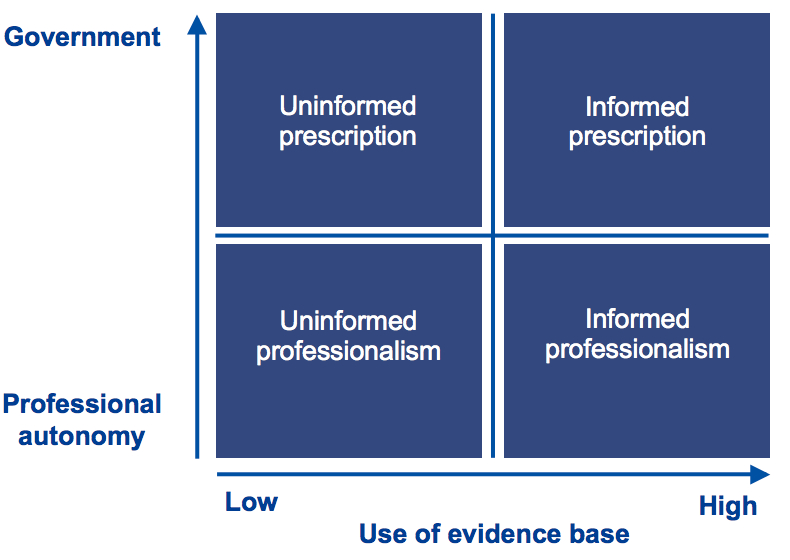

The recent history of British education reform bears out this distinction. Blair’s governments did a good job of narrowing achievement gaps at the elementary school level, by aggressively tackling under-performance, especially in London. The aim of policy now is to retain strong accountability, especially for failing or weak schools, while giving others greater freedom and autonomy. It is the difference between relying on prescription or on professionalism. But Barber’s second key point is that however tight the grip of government, evidence remains king:

What about the United States?

As Whitehurst points out, the United States is in a “transformative” (in other words, very messy) phase in terms of school accountability and standards. A lesson from the UK is the need for an approach that is flexible enough to achieve two very different goals: force bad schools to get better and help good schools become great. Both are important for raising American levels of education and narrowing the opportunity gaps all the way up the distribution.

Commentary

The Barber Doctrine: Accountability and Autonomy for Schools to Close Opportunity Gaps

July 11, 2014