Socioeconomic status (SES) gaps in achievement are larger than in the past, and at least half these gaps are present at school entry. Neuroscience, developmental psychology, and economics point to importance of the early years—and the Social Mobility Summit devoted a session to examining the policies that might narrow gaps in early childhood. Although the evidence base on parenting programs has historically been weak, we now have evidence that some parenting programs can improve parenting and child outcomes. We also have strong evidence that preschool can help close gaps. And, we have more evidence than ever before about the valuable role played by the safety net, in particular, tax credits and food/nutrition programs.

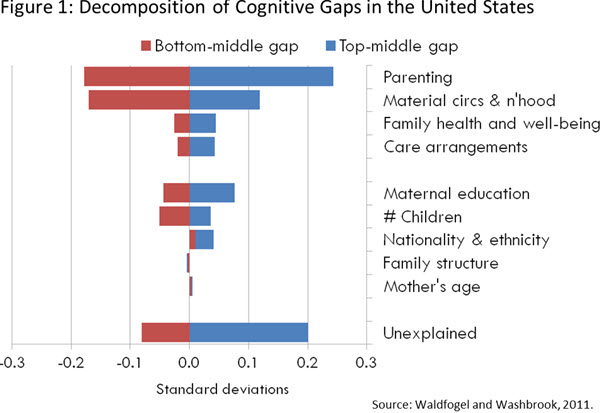

- Policies to improve parenting. Parenting consistently emerges as the single most important factor in SES gaps in school readiness (see Figure 1). But identifying effective parenting programs—that improve parenting and child outcomes—has been challenging. However, we now have good evidence that some programs are effective at both. This includes random assignment studies of the Nurse-Family Partnership, PALS, PEEP, Incredible Years, and Early Head Start.

- Early childhood education policies. Evidence from small-scale, model interventions shows conclusively that early childhood education can improve school readiness, and with larger effects for disadvantaged children. We now have good evidence that government policy can move more children into early childhood education and that such policy can help close gaps – and not just in the short-term. Reviewing the evidence, Chris Ruhm and I found that expansions of early childhood education yield benefits at school entry, in adolescence, and in adulthood, with particularly favorable results for disadvantaged children. We also found that pre-kindergarten programs in the U.S. have strong effects on cognitive outcomes for disadvantaged children.

- Policies to reduce poverty and material hardship. Even after controlling for other factors, a direct effect of poverty and material hardship remains (and may also affect children indirectly). So there is a role for policies to tackle poverty and hardship, particularly in early childhood, when families are more likely to be poor and when children may be most affected. Policies in this area include policies to boost the employment and earnings of low-income parents (through child care subsidies, higher minimum wages, last resort jobs, etc.). We also have stronger evidence today about the important role of the safety net, in particular tax credits and food and nutrition programs (reviewed in my chapter in Legacies of the War on Poverty).

The evidence indicates that high-quality interventions in early childhood can improve child outcomes and help close gaps. There are also some caveats:

- Not all programs are equally effective.

- High quality programs do not come cheap and may be hard to scale up.

- Early childhood policies may not fully eliminate gaps in school readiness, nor can they guarantee that gaps do not widen thereafter. There is also a role for policies to tackle the under-achievement of low-income children in the school years.

Commentary

Gaps in Early Childhood, School Readiness, & School Achievement: Policy Responses

January 27, 2014