Marriage is becoming an affluent pursuit, and social mobility is stagnating: two big contemporary American problems. Are they related?

Derek Thompson at The Atlantic thinks so. His “How America’s Marriage Crisis Makes Income Inequality So Much Worse”, suggests the changing landscape of marriage is fuelling the income gap. Of course, the importance of these changes in the shape of the family goes beyond inequality and mobility, but it is not possible to separate marriage and mobility.

Single mothers and social mobility

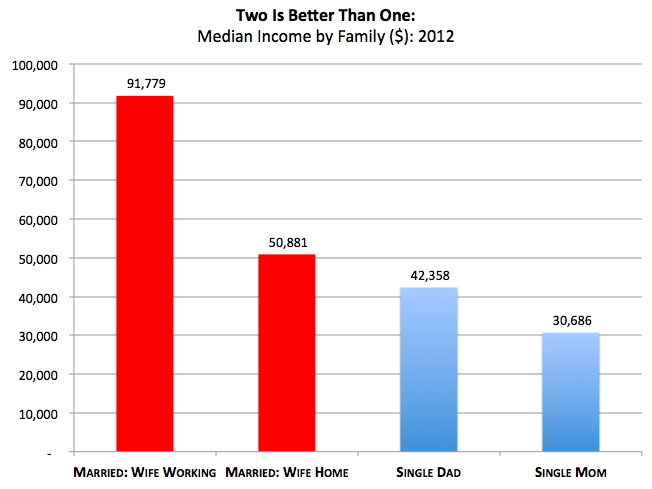

Having two earners is clearly better, in financial terms, than having one. It used to be that a breadwinning male was “head” of the household. But two heads are better than one: households with two working spouses have an income three times that of a single mother, as Thompson illustrates nicely:

The rise in single mothers matters for income inequality. But it’s a concern for social mobility too. On this blog, we have highlighted the rising number of single mothers among twenty-somethings—and what it means for the future prospects and mobility of children. Children of married parents have better life outcomes, in terms of education, health, and income—in large part because they have more resources available to them.

Assortative mating and social mobility

Thompson focuses briefly on what he calls the “marriage gap,” or what academics inelegantly call “assortative mating.” This signals the tendency of like to marry like: those who are college educated and high-earning marry each other; and those with less education and less income marry each other (if they marry at all).

Brookings has examined the role of assortative mating in the context of economic mobility and gender. One reason women stay in the income brackets of their parents is that they marry someone from a similar background: the earnings of a married woman’s husband bear as much resemblance to her parents’ income as her own earnings.

Marriages as childrearing institutions

Marriage, then, becomes another mechanism through which advantage is protected and passed on. Affluent, committed parents tend to get married, stay married, and raise their children together. Indeed, this is arguably now the main social purpose of marriage. As women have advanced in the workplace, the rationale for marriage has become about child-rearing, not income-sharing. As Shelly Lundberg and Robert A. Pollak put it in their paper “Cohabitation and the Uneven Retreat from Marriage in the U.S., 1950-2010”:

The primary source of the gains to marriage shifted from the production of household services and commodities to investment in children…Marriage is the commitment mechanism that supports high levels of investment in children and is hence more valuable for parents adopting a high-investment strategy for their children.

In the U.S., marriages are excellent institutions within which to raise children well and optimize their life chances. This lesson has not been lost on the affluent.

Commentary

The Marriage Crisis Hurts Social Mobility

October 3, 2013