Part 3 in a three-part series on inequalities in early childhood development.

Achievement gaps open up in early childhood, damaging chances of upward mobility—especially for those from poor backgrounds. The question is: what can we do about it?

The leading policy to address these early childhood gaps is pre-k, for which support is high but evidence is mixed. We know that a couple of very intensive early years programs, namely the Perry Preschool Project and the Abecedarian Project, showed big payoffs but also that it is not often appropriate to generalize from these programs. We also know that Head Start, our current federal early childhood program for low-income children, has no apparent lasting impacts, at least in terms of academics. In short, policy focused on early childhood education has promise but federal investment so far has had disappointing results.

President Obama has now proposed universal pre-k for 4-year-olds. Is this the solution for closing early achievement gaps and improving social mobility?

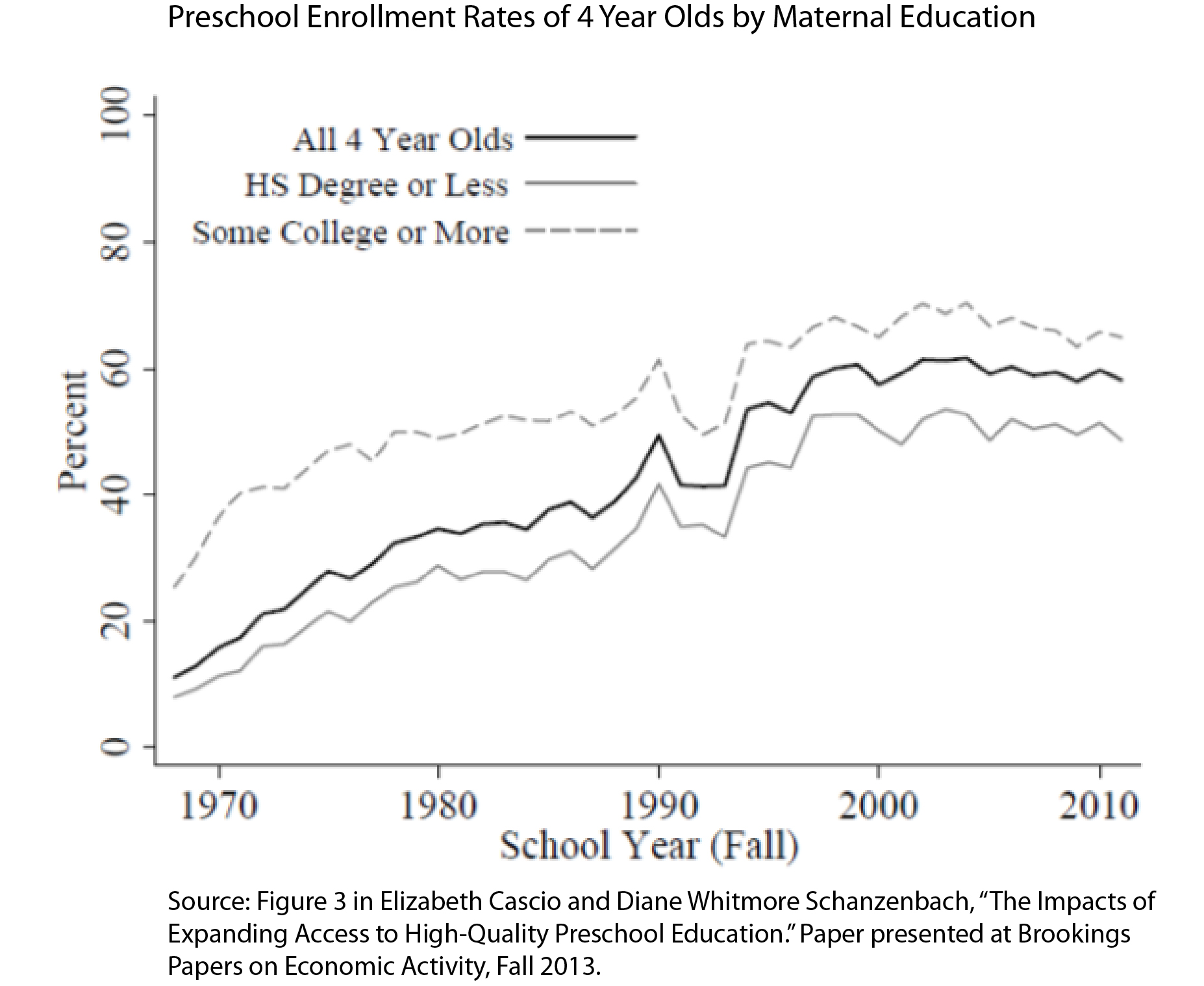

In a paper presented at BPEA last week, Cascio and Schanzenbach provide new evidence on the potential effects of Obama’s proposal. They found universal pre-k programs in Georgia and Oklahoma made it much more likely that disadvantaged children were enrolled in pre-k, but there was also a big shift of more advantaged children from private pre-k to public, meaning higher costs for taxpayers. There is modest evidence that these programs improved test scores in later years, but only for the disadvantaged children. The implication is that Obama’s proposed program could create some cognitive advantages for low-income children—the principal beneficiaries—but may not be the most cost-effective approach.

Intriguingly, Cascio and Schanzenbach also found that with universal pre-k in place, less-educated mothers spent less time with their 4-year-olds overall but spent better quality time with their children when they were together: specifically, 25 more minutes per weekday doing activities with them such as reading, playing, and talking. In other words, pre-k may not simply substitute for parental investment in their children but may also improve it.

This is good news. We recently argued in “The Parenting Gap” that more investment should be focused on improving the home environment of disadvantaged children. We concentrated on direct parenting interventions like home visiting programs, which are a small part of Obama’s proposal. Cascio and Schanzenbach’s work suggests that in fact pre-k might improve parenting, too, albeit indirectly.

High-quality pre-k and high-quality home visiting programs can both help to close early childhood gaps in parenting and in the development of cognitive skills. But quality is king.

Commentary

Early Childhood Achievement Gaps and Social Mobility (Part 3)

September 26, 2013