Over the past half century, the total volume of water used by people has nearly tripled, outpacing the global population increase. Regional crises related to water quantity and quality is a growing problem. Although water scarcity is an obstacle to maintaining supplies for human consumption, agriculture, industry, and ecosystems, in many regions access to freshwater is also a matter of national security.

Reuters/Eliana Aponte – Tanks are filled with water in a poor neighborhood in Mexico City

The need for assured freshwater supplies has led to transboundary water competition, human migration, and political conflict. Properly identifying the underlying causes of freshwater vulnerability is critical to developing successful strategies and policy interventions needed to address future challenges. Research conducted by the Global Freshwater Initiative (GFI) at Stanford University attempts to do just that.

Four categories of freshwater vulnerability

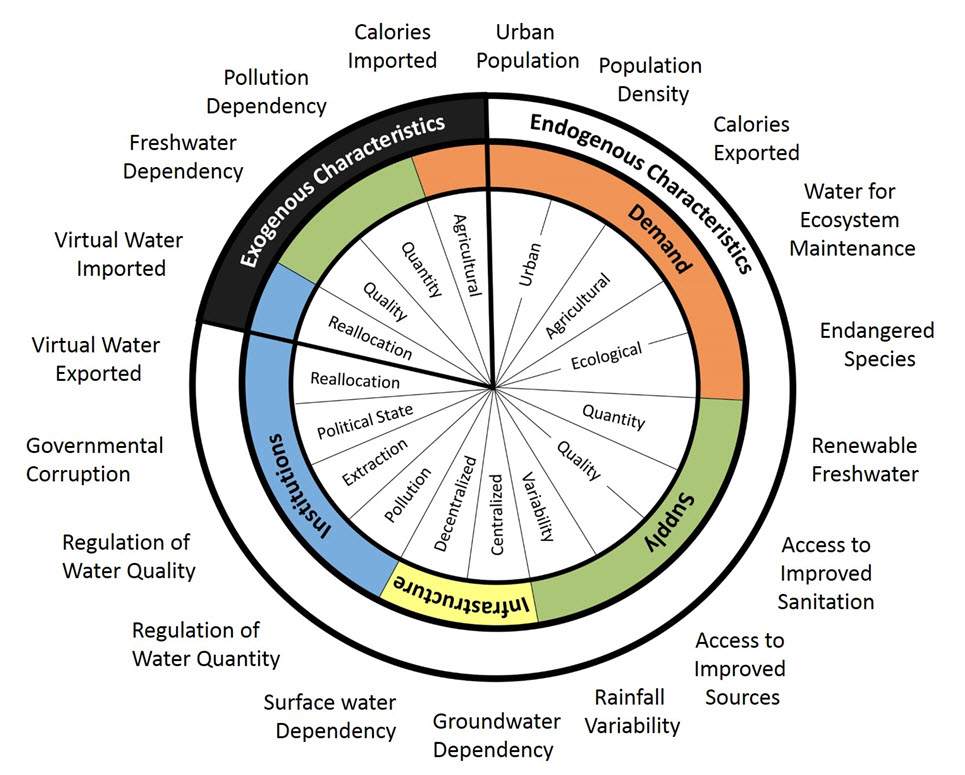

Using a comprehensive assessment approach, groups of countries with similar vulnerabilities are identified, thereby providing insights into both the nature of unique patterns of water supply problems and what could be successfully-targeted policy interventions. Freshwater vulnerabilities fall into four categories: demand, endowment, infrastructure, and institutions. These are quantified using 19 characteristics (figure 1).

Figure 1: Characteristics of freshwater supply vulnerability used as the basis for analyzing 119 low-income countries throughout the world. This figure is based on one in the recent paper: Padowski, J. C., Gorelick, S. M., Thompson, B. H., Rozelle, S., and Fendorf, S. (2015). Assessment of human–natural system characteristics influencing global freshwater supply vulnerability. Environmental Research Letters, 10(10), 104014.

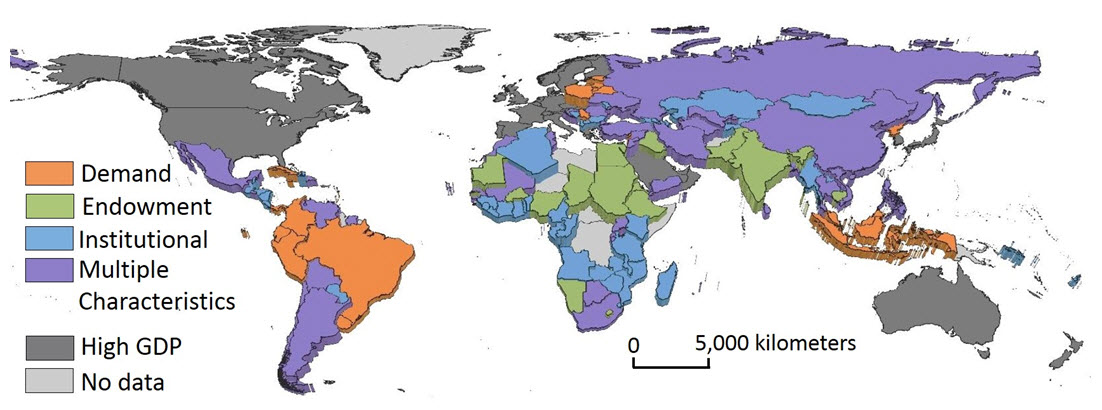

We analyzed vulnerability characteristics in 119 low-income countries (those with less than $10,725 per capita per year). Our assessment shows that all of these countries exhibit a moderate level of vulnerability in at least one characteristic, with institutional vulnerability being dominant in 37 percent of nations, most frequently in the form of governmental corruption (lack of transparency).

Regional characteristics and patterns

Regional characteristics and differences exist. In northern Africa and South Asia vulnerability results from low volumes of renewable freshwater, high freshwater dependency on neighboring countries, and poor access to sanitation that threatens freshwater supply. Latin American and Southeast Asian countries, meanwhile, are dominated by demand vulnerability as a consequence of large urban populations and a substantial amount of renewable freshwater being devoted to ecosystem maintenance.

The study identified 25 nations having a set of critical and severe freshwater supply vulnerabilities (figure 2). Of greatest concern are Jordan, Djibouti, and Yemen. These three countries have in common: low rainfall, limited surface water storage, excessive groundwater mining, high dependence on transboundary waters involving water-use of their neighbors, and importation of most food calories (virtual water) due to an inability to maintain sovereign food security. Djibouti and Yemen also suffer from significant government corruption (lack of transparency). While this is not the case for Jordan, in terms of freshwater supply it is still among the most severely vulnerable nations. Supply vulnerability is a particularly growing concern as Jordan has been serving as host to over 600,000 Syrian refugees since the beginning of the Syrian civil war. This large population influx further exacerbates water scarcity and demand challenges in Jordan. Syria’s damming of the headwater tributaries of the Yarmouk River before it flows into Jordan is a prime example of Jordan’s water supply vulnerability problems.

Figure 2: Number of freshwater supply vulnerability characteristics and dominant cause of vulnerability by country. The degree of vulnerability is reflected by the extruded height. The dominant type of vulnerability is shown by color. This figure is based on the one appearing the recent paper: Padowski, J. C., Gorelick, S. M., Thompson, B. H., Rozelle, S., and Fendorf, S. (2015). Assessment of human–natural system characteristics influencing global freshwater supply vulnerability. Environmental Research Letters, 10(10), 104014.

Similar patterns of freshwater vulnerability are found among countries that in some cases are in close geographic proximity and, more surprisingly, in other cases are not. Examples of the former include Iran, Egypt, and Algeria, which are in the same general region and experience similar supply vulnerability characteristics. They each have relatively large urban populations, limited renewable freshwater, steady aquifer depletion, and exhibit a distinct lack of governmental transparency. On the other hand, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Guatemala are distant from one another, yet they have similar attributes that make their freshwater supplies vulnerable. Each of these countries has relatively high population density and high numbers of endangered species that need to be protected, so they are dealing with high environmental and domestic sector demands. Vietnam and Sri Lanka lack government transparency and mechanisms for enforcing water-use regulations.

Properly identifying the underlying causes of freshwater vulnerability is critical to developing successful strategies and policy interventions needed to address future challenges.

Study conclusions

The study suggests three valuable insights:

- First, freshwater supply vulnerability involves a multitude of natural and human system characteristics beyond water scarcity and in-place infrastructure.

- Second, policy interventions that are effective for one region may be transferrable to other regions that have the same set of vulnerability characteristics.

- Third, institutional problems that involve a lack of regulation and enforcement as well as government corruption are the most dominant single category of vulnerability.

Our work points to a clear need for more comprehensive assessments of institutional factors in freshwater vulnerability analyses at regional or global scales.

Steven Gorelick

is the Cyrus Fisher Tolman Professor in the

School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences

at Stanford University and a Senior Fellow with the

Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment

.

Julie Padowski

is a Clinical Assistant Professor of the

Water Research Center

and

the Center for Environmental Research, Education and Outreach

at Washington State University.

Commentary

Identifying causes of global freshwater vulnerability

December 17, 2015