Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

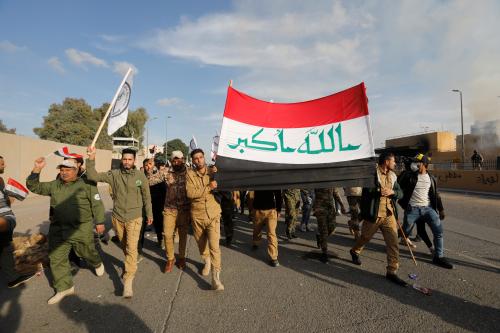

President Joe Biden’s decision to strike Iran-aligned groups in Syria last night follows a spate of rocket attacks launched against U.S. targets in Iraq this past week, including last week’s attack on U.S. and coalition personnel in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The Erbil attack was President Biden’s first major test with Iran, an escalation and provocation carried out by Iran-aligned militias that killed one civilian contractor and wounded nine others. It also resulted in the death of one Iraqi civilian. The 14 rockets launched by Iran’s proxies constituted the first major attack by such groups to take place under the Biden administration’s watch.

The U.S. strike targeting Ketaib Hezbollah and Ketaib Sayyid al-Shuhada is a welcome and measured response, one that balances the need to respond to Iranian proxy attacks while ensuring that countries like Iraq do not become engulfed in widespread violence and instability, which Iran and its allies can exploit to enhance their influence. It helps the Erbil and Baghdad governments prevent Iran’s proxies from discrediting their authority. Those governments seek to avoid becoming drawn into political and military conflicts with Iran’s proxies — which would play into the hands of the militias — and instead maintain their focus on addressing the economic crisis.

The merits of U.S. military action

U.S. policy on Iran does not have to emulate the confrontational stance adopted by the Trump administration, but can and should exercise the use of force against actors that threaten American personnel. This can additionally strengthen diplomatic negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. Iran believes it can enhance its bargaining power in these negotiations if it ups the ante by injuring or killing U.S. personnel, and believes the Biden administration has a high tolerance for Iranian proxy attacks on U.S. personnel. The most recent strike may to some degree alter this perception, and in the process deter further attacks on the U.S. and compel Iran to rein in its proxies. While it is unlikely that we will see a complete end to Iranian proxy rocket attacks, it is not entirely implausible that Tehran would look to moderate the scale and scope of future rocket attacks.

Essentially, the immediate objective of U.S. military action on Iran’s proxies should be to protect U.S. and coalition personnel currently engaged in the campaign to defeat ISIS. In the medium term, it should strengthen the viability of negotiations over the nuclear program, while in the long term it should strengthen the capacity of local institutions and actors in Iraq and Syria to constrain the space in which Iran’s proxies operate. What this means is that military action on its own will not address the problem. At the root of the challenge is the instability of the local political environment, as well as weak institutions that lack the ability to deliver services and security to communities, and hold to account the militia groups that operate outside of the state.

Where this leaves Iraq

To bolster the capacity of these institutions, it is critical to ensure that Iran’s proxies do not undermine and discredit the Erbil and Baghdad governments. Prime Ministers Mustafa al-Kadhimi and Masrour Barzani are currently addressing a plethora of crises, including an economic crisis that could take Iraq to the brink of socio-economic implosion. Erbil and Baghdad are not yet able to move directly against Iran-aligned groups, despite their aggression, provocations, and continued humanitarian atrocities. Doing so would invite a response from a powerful state sponsor (Iran) that has insulated its proxies from accountability and reprisal attacks for much of the past two decades. That paralysis allows Iran and its proxies to influence the political environment in their favor, expanding their hold over the political system and reducing Iraq’s prospects for addressing its economic crisis.

Any time the U.S. military conducts such strikes, it creates pressure on Iran and its proxies. This, in turn, mitigates the diminished political capital that Erbil and Baghdad suffer each time an Iranian proxy conducts an attack. Moreover, U.S. military action reduces the prospect that Baghdad or Erbil might respond impulsively to militia attacks, a reaction that can weaken their standing and play into militias’ hands. U.S. military action, to some extent at least, allows the leadership in Erbil and Baghdad to deliver on the promise of accountability in the wake of militia rocket attacks, and to retain their focus on economic reforms.

More broadly, U.S. military responses such as this produce more symbolic capital for Iraq’s leadership and reformists, allowing rivals of Iran-aligned groups to develop the local credibility that will be central to containing these actors. Iran’s proxies rely heavily on symbolism and narrative-building to expand their support bases, develop local resources, and position themselves as alternatives to their rivals or to state institutions. This strike — and further U.S. military action if or when these groups attack U.S. interests again — may diminish Iran-aligned militias’ symbolic capital. This could help eventually create internal cracks within proxy groups and the broader proxy infrastructure that spans Syria and Iraq.

Commentary

Biden’s decision to strike Iran’s proxies is a good start

February 26, 2021