Joe Biden’s election is a reprieve from Trumpism. Whether that break is permanent or temporary depends very much on the choices that Biden makes. And these choices may be the establishment’s last best chance to demonstrate that liberal internationalism is a superior strategy to populist nationalism, argues Thomas Wright. This piece originally appeared in The Atlantic.

For 18 months, Joe Biden was able to contrast his foreign policy with Donald Trump’s by painting in broad brushstrokes. He was in favor of alliances; Trump was opposed to them. He believed in American leadership in the world; Trump thought countries were taking advantage of the United States. Biden championed human rights; Trump sided with the autocrats.

Now that he is president-elect, Biden will need to be more specific about his foreign-policy stance. In many ways, Biden is a known quantity. He has a track record dating back almost five decades. But he will begin his term in a very different world than when he was vice president or a senator. He will face new, substantive challenges, including COVID-19 and a more assertive China. To meet this particularly difficult moment, he will need to master the politics of foreign policy — among different factions within his team, with a potentially obstructionist Republican Senate, and with skeptical American allies.

Biden cannot simply rely on competent technocratic management in foreign policy. His presidency may be the establishment’s last best chance to demonstrate that liberal internationalism is a superior strategy to populist nationalism. He must consider the strategic options generated by an ideologically diverse team, and he has to make big choices that are attuned to the politics of the moment, in the United States and around the world. Such a bold path is not one that a newly elected president with no foreign-policy experience could take. But he can.

To understand how Biden might approach his foreign policy, I spoke with half a dozen Biden advisers and people who worked closely with him in the Obama administration, as well as current and former congressional staff, Trump administration officials, and allied diplomats. I agreed not to identify them by name, to ensure their candor.

Within Biden’s team, an ongoing, but largely overlooked, debate has been brewing among Democratic centrists about the future of U.S. foreign policy. One group, which I call “restorationist,” favors a foreign policy broadly consistent with that of President Barack Obama. They believe in careful management of the post-Cold War order. They are cautious and incrementalist. They will stand up to China but will not want to define their strategy as a great power competition. They maintain high hopes for bilateral cooperation with Beijing on climate change, global public health, and other issues. They support Biden’s idea for a summit of democracies, aimed at repairing democracy and encouraging cooperation, but are wary of an ideological competition between democracy and authoritarianism. They favor a return to the Iran nuclear deal and intend to continue to play America’s traditional role in the Middle East. They generally support free-trade deals and embrace globalization.

A second group, which I call “reformist,” challenges key orthodoxies from the Obama era. Philosophically, these advisers believe that U.S. foreign policy needs to fundamentally change if it is to deal with the underlying forces of Trumpism and nationalist populism. They are more willing than restorationists to take calculated risks and more comfortable tolerating friction with rivals and problematic allies. They see China as the administration’s defining challenge and favor a more competitive approach than Obama’s. They view cooperation with other free societies as a central component of U.S. foreign policy, even if those partnerships result in clashes with authoritarian allies that are not particularly vital. They want less Middle East involvement overall and are more willing to use leverage against Iran and Gulf Arab states in the hopes of securing an agreement to replace the Iran nuclear deal. They favor significant changes to foreign economic policy, focusing on international tax, cybersecurity and data sharing, industrial policy, and technology, rather than traditional free-trade agreements.

Biden’s worldview is broad enough to be compatible with the restorationist and reformist schools of thought. He obviously trusts many of Obama’s senior officials and is proud of the administration’s record. At the same time, he chafed against Obama’s caution and incrementalism — for example, Biden wanted to send lethal assistance to Ukraine, when Obama did not. Biden has spoken more explicitly than Obama about competition with China and Russia, and he favors a foreign policy that works for the middle class. It is important to note that the legitimate and substantive disagreements between restorationists and reformists are between people who get along with each other. Restorationist sounds pejorative in the sense that the term looks backward, but it is not intended to be. Obama’s foreign policy was successful in many respects, and the case for restoring it is reasonable, as is the case for significant departures from it. Some officials are also restorationist on particular issues and reformist on others.

The progressives who staked out new ground on foreign policy during the primary campaign will be a significant force inside the Democratic Party in a Biden administration. Progressives believe foreign policy should primarily serve domestic economic and political goals. They are skeptical of high defense spending and want to demilitarize U.S. foreign policy, but they are also alarmed by the rise of autocracy globally and want to push back against it. Several Biden advisers, in particular Jake Sullivan and Tony Blinken, made a special effort to engage progressives from the Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders campaigns after the primary. Now that the election is over, progressives mainly focused on domestic politics are very much inside the tent shaping Biden’s economic agenda, but some foreign-policy progressives have adopted a more confrontational approach toward the Biden team, hoping to pressure it from the outside on China, Iran, and defense spending.

Biden should see these contrasting perspectives as assets, and proactively create a team that reflects the broader foreign-policy debate and avoids groupthink. But he will need to actively manage the different views. He should start by learning lessons from Obama. In late 2012, Obama chose John Kerry to be his second secretary of state because he was the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, was an old political ally, and was widely perceived to be the most logical candidate. Obama’s signature foreign-policy accomplishment in his first term was the pivot to Asia away from the Middle East, but Kerry wanted to pivot back. Obama returned to a Middle East-centric State Department, seemingly without intending to do so. Blinken, then Kerry’s deputy, was left to manage America’s alliances in Asia—something that he did effectively and that might fall to him now.

Similarly, Biden could unintentionally create a uniformly Obamian worldview in his national-security team, unless he purposefully decides to go another route. Biden’s governing goal should be a genuinely intellectually honest process in which fundamental assumptions and policies of restorationist, reformist, and progressive ideas are constantly stress-tested and assessed with an open mind. This process needs to be outcome-oriented and not devolve into the “more meetings” mindset that creates gridlock and trends toward the lowest common denominator. Biden needs a variety of strategic choices. As a seasoned foreign-policy leader, he is ideally positioned to adjudicate this debate and to choose among the options that it will present.

Biden should certainly entrust senior positions to people who tend toward the Obamian worldview, but he should also find roles for people who might advocate for a new direction, including Pete Buttigieg, Senators Chris Coons and Chris Murphy, and former officials Jake Sullivan, Toria Nuland, Kurt Campbell, and others who have written or spoken in favor of major policy changes since 2016. Sullivan is likely to take a domestic-policy job, but given his role in developing reformist ideas over the past four years, it is important that he also remain an influential voice on national security, and he is well positioned to help connect the domestic to the foreign. Given the substantive nature of the debate thus far and that it has generally been amicable, an ideologically diverse Cabinet should bring out the best in all factions, sharpening thinking and policy options.

Biden will need a variety of ideas because he faces significant political challenges at home. By any metric, Biden certainly has a mandate. He won 306 electoral votes and more popular votes than any president in history. However, the election was not the sweeping repudiation of Trump that Democrats craved. Trumpism has not gone away and instead appears to have transformed the Republican Party into a force for populist nationalism, including hostility toward international cooperation and skepticism about alliances.

The Republicans are well positioned to retain control of the Senate following the two runoffs in Georgia in January. If Mitch McConnell reprises the obstructionist role he played in the Obama administration, he could kill Biden’s domestic agenda on arrival. Many Biden Democrats believe that a successful foreign policy requires rejuvenation at home, so McConnell’s tactics may be a big problem. Republicans will likely put Biden’s nominees through intensive hearings, and they may be willing to reject appointees, particularly at the subcabinet level.

All Democrats and many Republicans agree on the need to repair and strengthen America’s alliances and partnerships, but this is more complicated than the campaign rhetoric made it appear. The year 2021 will not be like 2009, when Obama was widely greeted as a conquering hero, winning the Nobel Prize after less than a year in office, simply because of what his election signified. The world is a less cooperative and liberal place today. Just consider the rise of nationalist-populist governments in Brazil and India and the erosion of democracy in Turkey and Hungary.

America’s closest allies will all work with Biden and welcome the end of Trump’s erraticism, but they have lingering doubts about where things are headed. The Australian and Japanese governments, for example, are quietly concerned about Biden’s approach to China and are watching his early appointments very closely. The French worry that Democrats will leave Europe high and dry as they try to withdraw from the Middle East and from the war on terrorism more broadly so that they can pivot to the China challenge. The British are wondering whether Biden will invest in their special relationship, given that he opposed Brexit. Several officials I spoke with from America’s allies in Europe and Asia have reservations about the planned summit of democracies that Biden made a centerpiece of his election. They worry that the meeting could become an end in itself and be too inwardly focused and beset by problems about which countries qualify as democracies.

So how should Biden navigate this complicated landscape? Although he is absolutely right to claim a mandate and to convey optimism about the future, Biden must also be cognizant of the precariousness of his liberal-internationalist worldview. Liberalism is under siege at home and abroad. It will not automatically endure.

In COVID-19, Biden will inherit the greatest international challenge facing the United States since the height of the Cold War. The pandemic is a moment of global reordering — not to deal only with the coronavirus but also the underlying issues it revealed, including an uncooperative China and the vulnerabilities of interdependence. Biden must be ambitious at home and abroad, because these realms are inextricably linked. The tricky part is that he must construct a bold policy within the political constraints of Washington, where Democrats may not carry the Senate.

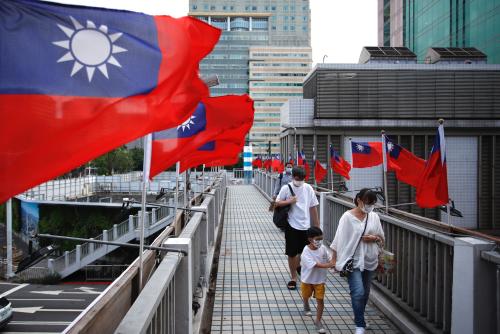

Biden should use competition with China as a bridge to Senate Republicans. Their instinct may be obstructionist, particularly because Trump is pressuring them not to recognize Biden’s win as legitimate, but many of them also know that the U.S. cannot afford four years of legislative gridlock if it is to compete with China. A number of Republican foreign-policy experts pointed out to me that some senators, including Tom Cotton and Ted Cruz, may be out for scalps, but that others, including Susan Collins, Joni Ernst, Mitt Romney, Marco Rubio, and Dan Sullivan, are mainly interested in the substance of Biden’s foreign policy, especially toward China. Biden, then, can use competition with the country to gain support for other political measures.

He can create goodwill with some of these Republicans by, in the first few weeks of his term, supporting pending legislation on investments in the semiconductor industry and 5G infrastructure, appointing assistant secretaries for Asia at the State Department and the Pentagon who can easily win bipartisan support, and showing that he is serious about using the Treasury and Commerce Departments to compete with China.

These efforts would lay the groundwork for crucial elements of Biden’s Build Back Better domestic program: targeted infrastructure investments, including clean technology; an industrial policy to compete with China on 5G, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence; a limited and strategic decoupling from China in certain areas; and bolstering the resilience of the U.S. economy to external shocks, which would include making supply chains more secure.

Although some in Biden Land support this bipartisan give-and-take, others, including many of the restorationists, are very skeptical of using competition with China as a framework for U.S. foreign and domestic policy. Some also have substantive reservations about any decoupling from China. They expect China to reach out for a reset early in 2021—probably regarding the pandemic and climate change—and would like to explore opportunities for cooperation. Foreign-policy progressives are also generally opposed to building Biden’s foreign policy around competition with China, believing that the strategy risks creating a Cold War.

These restorationist and progressive fears are overblown. Almost all of these early measures are about enhancing domestic competitiveness, not engaging in an arms race or a clash of civilizations. Indeed, Elizabeth Warren advocated for domestic reforms to compete with China during her presidential campaign. Domestic progressives are much more inclined than their foreign-policy counterparts to support this conceptual framework if it unlocks the politics of an ambitious domestic agenda, which will include new jobs through investments in clean technology—a vital part of a climate policy.

Getting serious about competing with China is also justified on the merits. Xi Jinping’s China has become more dictatorial and aggressive. Even the European Union, which is about as benign a geopolitical actor as China could hope for, has all but given up hope that engagement and cooperation will change China or fundamentally moderate its behavior, even on shared interests such as global public health. Cooperation with China on shared interests should occur, but we need to be realistic about the limits. To prevent competition with China from spiraling into outright confrontation, Biden should situate the strategy as part of a larger affirmative vision for strengthening the free world. This policy would include making free societies more resilient to external shocks such as pandemics and economic crises, fighting corruption and kleptocracy, standing up to autocratic countries that try to bully or coerce democracies, and combatting democratic backsliding. This approach would be more effective than organizing a global summit of democracies.

The inescapable political reality in Washington is that competition with China is the only way to persuade a Trumpian Republican Party of the benefits of international cooperation—whether through alliances providing a counterweight to Chinese power, through vying with China for influence inside international institutions, or through relying on international law to prevent Chinese revisionism in the South China Sea. Without the China component, Biden has no hope of creating any kind of domestic consensus around internationalism.

After addressing the China issue, Biden should shockproof U.S. foreign policy against the return of Trumpism in 2025. Republican senators may hope to harness populism for future elections, but they are, for now at least, committed to America’s alliances. Why not codify their support by introducing legislation that requires congressional approval if the United States is to leave NATO? Biden could proactively build redundancy into the alliance system by supporting EU security and defense cooperation, even if the action risks a duplication with NATO. Biden should also press Congress to enact new commonsense restraints on presidents—for instance on their ability to circumvent the confirmation and security-clearance procedures for appointees—to prevent a recurrence of Trump’s abuses of power. On climate change, he must prioritize carbon-emission cuts at the state and city levels, which are less likely to be stopped or reversed by Congress.

In managing relationships with allies, Biden cannot rely only on shared problems to bring them closer. He must also engage these leaders on their terms, paying special interest to their political situation and priorities. It would be a disaster if France were to fall into the hands of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in 2022, so Biden should bolster President Emmanuel Macron, including by showing solidarity with France in the face of a domestic terrorism threat. He should make a genuine effort to help Britain succeed after leaving the EU, as long as it respects its obligations under the Good Friday Agreement. And finally, a bipartisan consensus on China will reassure Japan and Australia.

Managing nondemocratic allies—including Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Hungary, and the Philippines—is more difficult. They will try to put him in a vise by flirting with Russia and China. Biden won’t succeed by appealing to the better angels of their nature, and he cannot be tricked into thinking that America needs these regimes more than they need America. Biden must be feared by the so-called strongmen before he can be respected by them. He must show that he is willing to push back and that he can wield power and generate leverage more effectively than Obama. He must introduce red lines that cannot be crossed. Only then can transactional cooperation on matters of mutual interest really occur.

Biden’s election is a reprieve from Trumpism. Whether that break is permanent or temporary depends very much on the choices that Biden makes. Biden must act with a degree of urgency and boldness to demonstrate that his brand of liberal internationalism effectively addresses the real concerns and anxieties Americans have about the world.

Commentary

The fraught politics facing Biden’s foreign policy

November 22, 2020