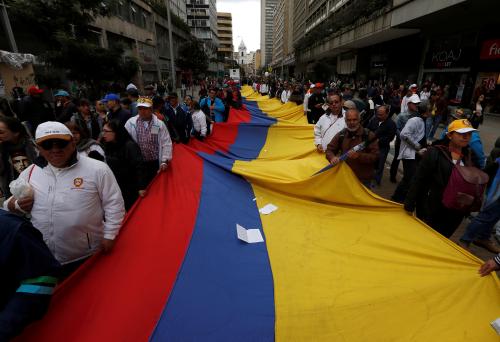

The historic peace agreement between the government of Colombia and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionaras de Colombia—Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP), the country’s largest armed rebel force—is facing its most serious test yet. The accords ended over 50 years of a conflict that killed at least 260,000 Colombians and displaced nearly seven and a half million people. This historic achievement, widely applauded by the international community and key sectors of Colombian society, nonetheless has encountered major challenges in political legitimacy and implementation.

After an initial and largely successful phase of demobilization and disarmament, the country’s main actors are struggling with the more costly and destabilizing stages of reintegration of ex-fighters, soaring illicit drug production, rural underdevelopment, and reparations to victims.

The most daunting challenge, however, is posed by the accord’s complex approach to truth, justice, and reconciliation. Recent events suggest that President Iván Duque Márquez, elected last June on promises to revise key provisions of the accord, is determined to undermine the pact’s central bargain of peace for conditional amnesty in order to satisfy his conservative coalition partners who never fully accepted the deal. And guerrillas who never signed up for or have since left the arrangement are pairing up with other criminal armed groups to destabilize a security environment already under growing strain from the influx of over 1.2 million people fleeing the crisis in Venezuela.

A rocky peace from the start

Colombia’s ongoing attempts to forge peace among its disparate armed groups reached new heights in November 2016 when the government of President Juan Manuel Santos signed a comprehensive peace accord with the FARC-EP.

Notably, Colombian citizens narrowly rejected the deal in a national plebiscite held in October 2016 that drew only 37.4 percent of voters; this led to some important revisions adopted by the parties and quickly approved by both houses of Congress. Former President Álvaro Uribe, Santos’ immediate predecessor whose military operations against the FARC had severely weakened the rebel army, came out strongly against the peace agreement on grounds it was too lenient toward FARC guerrillas and did not do enough to break up their criminal activities.

Uribe’s protégé, Iván Duque Márquez, won the election as president in June 2018 on a promise to fix the agreement’s shortcomings and, since winning office, has consistently slow-rolled its implementation. The latest blow came in March this year when President Duque vetoed portions of the peace accords’ controversial transitional justice chapter, prompting leaders of both the FARC political party and the pro-peace Santos faction to declare the move a grave threat to the peace accords, which had previously been ratified by the Constitutional Court and the Congress.

An ambitious plan for transitional justice

Not surprisingly, these latest twists and turns hinge on the issue of accountability for human rights violations committed by ex-combatants over decades of violent conflict, one of the most vexing for any peace process to manage. The Colombian peace accord, compared to others, is more advanced in its comprehensive and detailed approach to the problem, integrating all four components of the transitional justice paradigm—the right to truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence.

The grand bargain of the accord was to dismantle the FARC’s fighting capacity and reintegrate its members into political and civilian life in exchange for amnesty for politically-motivated crimes such as rebellion. They must also provide full cooperation with the mechanisms established for truth, justice, reparations, and non-recurrence, including pledges never to resume fighting. If the relevant components of the transitional justice system decide cooperation is forthcoming, ex-fighters facing allegations of serious crimes may earn reduced sentences of restricted liberty as well as legal certainty for a return to normal life. Failure to cooperate with the transitional justice system, however, subjects them to more stringent criminal penalties, including jail time. A continuation or a return to armed rebellion or other criminal activity would allow the state to use force to quell the violence, as it is doing with groups that have not yet signed any settlement with the government.

These judicial accountability elements of the peace accords are complemented by other components that should, if implemented appropriately, lead to improved conditions for achieving the ultimate goal of the process—a sustainable peace. The truth and reconciliation commission, which launched its three-year mandate last November, is a bedrock piece of the puzzle that will help knit together a historical narrative and healing process that should give voice to the thousands of victims who suffered disproportionately from the conflict. A commission to search for missing persons could bring some closure to families still waiting for news of the fate of their loved ones. A national system for reparations for victims offers individual and collective approaches to land, health and employment services, financial compensation, and other forms of reparations. Guarantees of non-recurrence rest principally on a combination of accountability for serious human rights abuses (including for agents of the state and third parties who committed violations), protection for ex-combatants and social leaders long victimized by state and non-state armed forces, and prosecution of their attackers.

Variable implementation

The first stages of the agreement’s implementation—disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR)—have proceeded relatively well, with 6,934 FARC-EP fighters and 2,256 non-combatant FARC-EP militia members registered and grouped in 26 different camps around the country for the purpose of turning in their weapons and beginning an official process of undertaking productive work, education, and job training. At the end of the disarmament process, the United Nations verified the collection and neutralization of almost 9,000 FARC-EP weapons and 1.7 million ammunitions. Each registered FARC-EP member, once demobilized, received a one-time economic benefit of two million pesos (equal to $675 at the time of disarmament in August 2017) to facilitate their reintegration into civilian life. The FARC-EP reconstituted itself into a political party and participated in the 2018 national elections, which were the most peaceful and participatory in decades. While the FARC candidates performed badly at the polls, they will still occupy five guaranteed seats in each house of the legislature through 2026, as agreed in the negotiation (to Uribe’s great dismay).

Other aspects of the accord’s implementation, however, are going badly and/or falling behind schedule. The government’s plan for rural development, for example, which should be a linchpin for addressing the root causes of the conflict, lacks key details, funding, or progress on issues like land registration (cadastral system). It is also confounded by the longstanding links between armed groups and coca production, a problem that has only worsened since the signing of the accords over two years ago. In 2017, coca cultivation in Colombia reached an all-time high of 171,000 hectares. Duque’s plan for complementing illicit crop substitution (already facing budget cuts) with forced eradication, including a return to aerial spraying of glyphosate, a known carcinogen, has drawn heavy opposition, as has his administration’s preference for agribusiness over traditionally marginalized small landholders and peasant farmers.

Dangerous shortcomings

The most serious problems, however, revolve around the justice and accountability elements of the system. The peace agreement’s drafters, for good and ill, designed a special judicial process (known as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace [JEP]) that is remarkably complex, with three chambers composed of 18 total magistrates and a peace tribunal composed of four sections and 20 magistrates. Along with the other components of the burgeoning transitional justice bureaucracy, costs are expected to reach around $1.5 billion to implement. The 2019 budget allocation for the JEP alone is around $96 million. It operates alongside an ordinary justice system that is notoriously dense and slow, with multiple opportunities for delay and derailment and high rates of impunity. Despite a reputation for having a legalistic culture, Colombia scores poorly against international justice and law standards. Compared to other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Colombia ranks 20th out of 30 countries in rule of law and 80th out of 126 countries worldwide.

Conservatives and other opponents of the peace deal are particularly worried about the JEP’s interpretation of the accord’s language granting armed forces personnel “differentiated treatment” for alleged violations. This special handling, which they claim entitles them to greater leniency, is derived from their legitimate role as state agents authorized to maintain a monopoly on violence in accordance with international and Colombian provisions of human rights and humanitarian law. This “differentiated treatment” is important because some former and current military and defense officials are vulnerable to charges of war crimes, most notoriously for the “falsos positivos” scandal in which armed forces personnel killed innocent civilians then presented them as armed rebels, often in exchange for a casualty “bonus.” Their call for a separate transitional justice process that they hoped would lead to more lenient treatment, however, was rejected by the Constitutional Court.

These sectors also want, among other things, to reinforce provisions that would remove any benefits of the transitional justice system from those who engage in criminal conduct after the peace agreement went into force on December 1, 2016, and transfer any cases of sexual crimes against children to the ordinary justice courts. These latest claims not only raise procedural questions that will further delay progress but suggest that Duque has little political interest in a serious justice and accountability process. The JEP, however, appears undaunted, believing it has the legal authority, ratified by the Constitutional Court, to move ahead with its investigations and hearings.

While these legal and political skirmishes play out, one critical element of the peace accords is tragically failing—the protection of human rights defenders, leaders of social movements, and political opposition figures. The official protection system, which is central to the non-recurrence features of the accord, is operating but unable to defend these leaders effectively from attacks perpetrated by a collection of armed groups (including remnants of paramilitary units demobilized in an earlier peace agreement), drug traffickers, and other violent actors intent on disrupting the peace process. The numbers are chilling: As of the end of 2018, the United Nations has received reports of the murder of 454 human rights defenders and social leaders since the signing of the peace agreement, and of the 163 murders they have verified, 110 occurred in 2018. The United Nations has also verified the murder of 85 former FARC-EP members. These ongoing attacks, and the relatively high rates of impunity, underscore the fearsome challenge of building peace in the midst of so much conflict and violence.

“Death by a thousand cuts”?

In sum, the Colombian model of a comprehensive system of truth, justice, reparation, and non-repetition is facing a series of daunting tests and may not be able to withstand the current “death by a thousand cuts” tactics of Duque and his allies. While its ambitious scope and complex details may have looked sophisticated and intelligent at the time, in practice the system may prove too cumbersome and slow to prevent a return to conflict levels of the past. Non-recurrence elements like vetting and reform of the security sector, for example, are largely missing from the agreement, and longstanding grievances around land ownership got short shrift.

If, on the other hand, the key actors responsible for implementation are able and willing to build on the early positive returns around disarmament and demobilization, carry out effective reparations and reintegration programs (especially in rural areas), and improve protection for political opposition and social movement leaders, they may be able to navigate their way through the thicket of the justice and accountability stages of the project. But such an outcome won’t be easy, especially given Duque’s readiness to protect his right flank. The truth, justice and reconciliation components of the system, if implemented in a balanced and authoritative way, could serve as the indispensable keystone bridging the main divides between a sustainable peace and a return to conflict. They will need all the help the international community can provide.

Brookings intern Amalia Coyle provided key research assistance for this piece.

Commentary

Is Colombia’s fragile peace breaking apart?

March 28, 2019