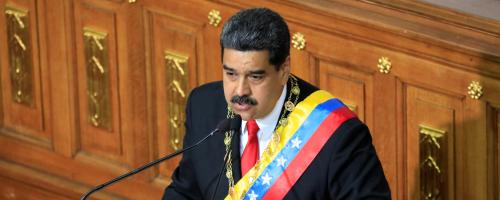

Venezuela’s National Assembly should now follow up its bold move this week by adopting a comprehensive plan to repair and restructure the country’s tattered institutions, write Dany Bahar, Ted Piccone, and Harold Trinkunas. This piece originally appeared in The Hill.

The political crisis in Venezuela has reached a tipping point that may lead to a peaceful return to democracy or yet more violence and despair. How the United States handles the situation could spell the difference between a successful transition back to democracy, deepening autocratic rule or outright civil war.

Contrary to claims that this is a U.S.-sponsored coup, the Venezuelan National Assembly, led by opposition parties freely and fairly elected by the Venezuelan people in December 2015, has asserted its authority under the constitution to organize a transitional government and prepare for new elections.

Since 2018, both the opposition and a significant coalition of democratic governments from Latin America, North America and Europe have rejected Maduro’s re-election as president as illegitimate due to widespread fraud.

With the expiration of Maduro’s first term in office on Jan. 10, the opposition claims the office of the presidency is now vacant. In Maduro’s place, they have elevated Juan Guaidó, who as president of the democratically-elected National Assembly is next in the constitutional line of succession.

President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo quickly endorsed Guaidó’s authority, called on Maduro to refrain from any violence against peaceful protestors and urged him to step aside.

At Guaidó’s request, the U.S. announced $20 million in additional humanitarian assistance to help Venezuelans suffering from massive inflation, shortages of food and medicine and spiraling insecurity. Meanwhile, Trump declared that “all options are on the table.”

The United States and its democratic partners in Latin America and Europe are on the right track in voicing strong support for Juan Guaidó, Venezuela’s new interim president. But Nicolás Maduro, the embattled autocrat in power, is claiming Washington is fomenting a coup, justifying efforts by Maduro’s allies in China, Russia and Turkey to weigh in.

The standoff in Caracas between two presidents claiming a democratic mandate raises the tricky question of who decides the legitimacy of a country’s government. Many leading democracies are quick to criticize foreign elections when they are manipulated through fraud and repression, but they rarely if ever deny recognition to the winner, even when the election is in dispute.

However, governments of the Americas have agreed that absolute state sovereignty is bounded by the rules of the Inter-American Democratic Charter (of which Venezuela is a signatory). The charter states that all citizens have a right to representative democracy organized through free and fair elections, and their governments have an obligation to promote and defend it.

Assuming Maduro, who so far retains the support of the military top command, will dig in, the Trump administration should move quickly to keep the pressure on, including by further tightening targeted sanctions on Venezuela’s most corrupt officials.

They should not, however, threaten or deploy military force. This would surely lead to the end of the democratic opposition’s ability to claim a legitimate mandate to govern Venezuela and bring the country closer to the abyss of civil war. It would also risk losing the backing of the international coalition that supports interim president Juan Guaidó.

The National Assembly should now follow up its bold move this week by adopting a comprehensive plan to repair and restructure the country’s tattered institutions. It has already adopted decrees offering amnesty to military personnel who support a return to democracy, and it has begun considering how to restructure CITGO, a key U.S.-based oil asset.

This is a good start but much more needs to be done to signal to Venezuelan nationals at home and abroad and international constituencies that they have the will and capacity to govern.

In the meantime, the international community should support Venezuelans by providing additional humanitarian assistance to frontline South American states hosting the over 3 million refugees who have fled the country, some of whom are now facing violent xenophobic attacks.

The U.S. and its allies should ramp up international pressure on money launderers and shell companies that shelter dirty Venezuelan money. They should also work together to restrict Maduro’s ability to benefit from Venezuela’s businesses, but this should be coordinated with a broader political strategy designed to end the stalemate.

In addition, the United Nations secretary general should urgently appoint a personal envoy to serve as a focal point for the multinational friends of Venezuelan democracy group now rallying behind the National Assembly and supporting U.N. Security Council action.

Building an off-ramp for the Maduro regime will be difficult. But a combination of rising costs on Maduro’s inner circle through targeted sanctions and prosecutions, reassurance to the military’s rank and file that they will benefit from a transition to democracy and positive incentives of economic assistance by entities willing to negotiate with the new interim government (such as the International Monetary Fund and the Inter-American Development Bank) will make legitimate democratic change, in accordance with Venezuela’s constitution, more likely.

Commentary

Venezuelans must lead in building an off-ramp for Maduro

January 28, 2019