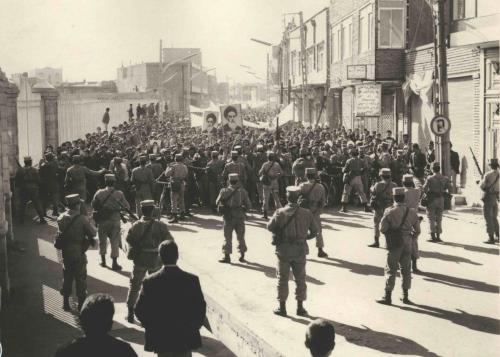

Like other major revolutions—such as the French and the Russian—the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran did not remain a domestic affair. Its authors and Iran’s new ruling elite were determined to export their revolution, but the impact of that determination was not readily apparent. The regime needed time to consolidate, to go through internecine conflicts, and to see through the protracted Iran-Iraq war that Iraq started.

But as early as 1982, the effort to mobilize and recruit Shiite communities in the Middle East was manifested in Lebanon. That effort, furthermore, was conducted in partnership with the Islamic Republic’s first regional ally, Hafez Assad’s Syria, a country dominated by members of a Shiite sect. By the early 2000s, Iran’s quest for regional hegemony and the resources it brought to bear in the service of that end came to rattle the Middle East. In recent years, these ambitions have been particularly evident in the Syrian civil war.

Iraq and Turkey

Iran’s regional drive was facilitated by the 2003 American invasion of Iraq. Washington’s action destroyed Iran’s arch enemy, Saddam Hussein, removing an obstacle to the westward projection of Iranian influence and transferring power in Iraq to the Shiite majority. Instead of a hostile neighbor, Iran now faced a fertile field for building its influence.

During the same years, another development took place that had a profound impact on the regional politics of the Middle East: the emergence and consolidation of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Islamist regime in Turkey. Iran and Turkey are neither enemies nor allies, but the parallel unfolding of Iran’s quest for regional hegemony and Turkey’s return to a central position in the Middle East transformed the region’s politics.

During the same years, another development took place that had a profound impact on the regional politics of the Middle East: the emergence and consolidation of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Islamist regime in Turkey. Iran and Turkey are neither enemies nor allies, but the parallel unfolding of Iran’s quest for regional hegemony and Turkey’s return to a central position in the Middle East transformed the region’s politics.

During most of the 20th century, the two successor states of the Ottoman and Persian Empires played only a limited role in Middle Eastern politics. The Shah of Iran did have foreign policy ambitions, and his impact on the Middle East was felt mostly in the region’s east and in its petro-politics. Iran’s ability to project power and influence in its immediate environment and beyond was constrained by Soviet pressure and domestic problems. Turkey, for its part, was ruled by a secular elite oriented toward Europe. As such, during most of the latter half of the 20th century, the regional politics of the Middle East were shaped mostly by the dynamics of inter-Arab relations and by the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Iran’s quest for regional hegemony after 1979 and Turkey’s shift away from Europe to its neighborhood (sometimes called Neo-Ottomanism) transformed the region. The Middle East was now joined by two, large, powerful Muslim states. The impact of their new roles was magnified by the atrophy of the Arab system and the diminished influence of major Arab states such as Egypt and Iraq. One important illustration of the new regional reality is the Astana Forum—composed of Russia, Iran, and Turkey—that since 2017 has been the major arena of the efforts to resolve the Syrian crisis. Not a single Arab state is a participant in that forum.

Of the two new actors, Iran is the more ambitious and more active. It is driven by religious zeal; the geopolitical ambitions of a successor state to a great imperial past; and the anxieties of a regime worried by the enmity of the United States and such regional enemies as Israel, Saudi Arabia and, until 2003, Iraq. The Iranian leadership may well see some of its actions as defensive, but they serve in fact to exacerbate the anxieties of its rivals, thus creating a vicious cycle of defensive-offensive action and reaction.

Egypt, Lebanon, and Israel

Iran’s progression as a Middle Eastern power was punctuated by opportunity and challenge.

One such opportunity was provided by the toppling of Hosni Mubarak’s regime in Egypt and the rise to power of Mohammed Morsi’s government. In response—and for the first time—Iran sent warships through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean Sea. Although only a single act, it provided a clear indication of Iran’s interests in expanding beyond its position in the region’s east and reaching the Mediterranean.

By that point, Iran had already established itself firmly in Lebanon (through Hezbollah) and in the Gaza Strip (through its support of Hamas). Iran’s efforts to mobilize and harness the Shiite community in Lebanon go back to 1982. (Though in fact, the investment in Lebanon’s Shiite community began in the days of the Shah). Of revolutionary Iran’s early investments in foreign policy, the investment in Lebanon proved to be the most effective. Hezbollah gradually became the most powerful actor in Lebanon, more powerful than the state and the Lebanese army. Championing Hezbollah enabled the Islamic Republic to claim the mantle of leading the conflict against Israel at the time when Arab regimes, including its Syrian allies, entered into a peace process with Israel. By providing Hezbollah with a huge arsenal of rockets and missiles, Iran was building a deterrent against a prospective Israeli or American attack on its nuclear program. The course and outcome of Israel’s second Lebanon war in 2006 demonstrate Tehran’s effectiveness in its trilateral partnership with Bashar Assad’s Syria and Hezbollah.

For the Iranian leadership, Israel was not merely a competitor for regional influence or an extension of the American arch-enemy (the “Little Satan”). According to Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment:

“Distilled to its essence, Tehran’s steadfast support for Assad is not driven by the geopolitical or financial interests of the Iranian nation, nor the religious convictions of the Islamic Republic, but by a visceral and seemingly inextinguishable hatred of the state of Israel. Senior Iranian officials like Ali Akbar Velayati… have commonly said ‘The chain of resistance against Israel by Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, the new Iraqi government and Hamas passes through the Syrian highway… Syria is the golden ring of the chain of resistance against Israel… Though Israel has virtually no direct impact on the daily lives of Iranians, opposition to the Jewish state has been the most enduring pillar of Iranian revolutionary ideology. Whether Khamenei is giving a speech about agriculture or education, he invariably returns to the evils of Zionism.”

The Arab Spring, which resonated across the Arab world, provided Iran with additional opportunities: the revolt against the Bahraini government (a Sunni regime dominating Shiite majority) was suppressed by Saudi Arabia, but the civil war in Yemen created an arena where Iran has been stoking the fires and Saudi Arabia has not yet been able defeat its rivals.

Syria

But it was Syria where the repercussions of the Arab Spring confronted Iran first with a major challenge and then with a major opportunity.

As the demonstrations against Bashar Assad developed into the Syrian civil war, Iran detected a severe challenge to its regional policy. If the Syrian regime—Iran’s oldest regional alliance—fell, it would be a major blow to Tehran and Hezbollah’s position in Lebanon could become untenable. Iran therefore rallied to support the regime, first by providing military aid, then by dispatching Hezbollah and other Shiite militias (from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan), and in 2014 sending its own troops (like the United States and Russia, Iran was and is sensitive to casualties and preferred to delegate fighting). In 2015, when the regime faced a prospect of collapse, the Iranians helped persuade Russia to send its air force to Syria, promising to provide the “boots on the ground” itself.

At the height of the Syrian civil war, Assad’s regime—supported by Russia, Iran, and the latter’s auxiliary forces—fought against a motley group of opposition forces armed and financed by regional Sunni states (Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Jordan) as well as by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. The joint Iranian-Russian effort met with success and led, in December 2016, to the capture of Aleppo from anti-government forces, the turning point that marked the regime’s victory in the Syrian civil war.

This conflict was compounded and for some time overshadowed by the rise of ISIS in both Iraq and Syria. ISIS and other jihadi groups were, among other things, a manifestation of Sunni opposition to the Shiite takeover in Iraq and Alawite domination of Syria and had a sharp anti-Iranian edge. The Obama administration, reluctant to join the war against the Assad regime, had no ambivalence about organizing and leading a large international coalition against ISIS, thus sharing an interest with Iran.

In addition, Iran’s ambitions in Syria led to a direct military conflict with Israel in 2018, with Israel determined to prevent a repetition of Iran’s success in building military infrastructure in Syria directed against Israel (as it had done in Lebanon). Until then, Iran and Israel fought indirectly in Lebanon and conducted a shadow war over Iran’s nuclear program.

Iran’s success in its Syrian venture inflated its self-confidence, and Tehran has now sought to take advantage of its success in Syria and expand its regional influence. Whereas before 2011, Tehran saw Syria as an ally and as a partner providing access to Lebanon and Hezbollah, as of 2016 Iran began to see Syria as an asset in its own right as a second front against Israel in addition to Lebanon. Related to its interest in having a presence near the Mediterranean, Iran sought Syrian agreement to build a naval base on the Syrian coast and to embed itself in Syria with strategic infrastructure (including long-range missiles and missile production facilities). Iran has sought to build what has become known as “a land bridge” through Iraq and Syria to Lebanon; Iranian supplies to Lebanon had previously been provided by air, by sea, and only occasionally over land. The air and sea routes had challenges, so secure access by land would be a significant improvement for Iran’s access to the Mediterranean. In November 2016, Chief of Staff of the Iranian Army General Mohammed Hussain Baqri declared in front of Iranian naval commanders that in the future, Iran might construct long-range naval bases on coasts, on islands, or as floating bases, and that it could possibly build bases on the coast of Yemen or Syria.

The ongoing question of Iran in its neighborhood

And so, as it marks the 40th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, Iran finds itself as a major actor in a transformed Middle Eastern system shaped to a considerable extent by its own actions. It is deeply invested in two crises, in Syria and in Yemen, that are still unfolding, and is confronted by a hostile American administration whose willingness to match its anti-Iranian rhetoric with action is uncertain.

Forty years after its birth, the Islamic Republic is still fueled by a blend of religious zeal, geopolitical ambitions, and vested interest. The question remains open as to when—as has been the case with other great revolutions—a phase of consolidation and moderation will set in.

Commentary

How Iran’s regional ambitions have developed since 1979

January 24, 2019