On November 21, 1979, a few hundred student protesters from the Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad stormed the U.S. embassy in that city, setting it on fire. They took one embassy employee hostage, and their aerial fire killed a 20-year-old marine. About 140 people assembled in the embassy’s vault for five hours while they waited for the Pakistani army to disperse the rioters. It later emerged that the students were part of the Jamaat-e-Islami Islamist party, which had been emboldened under Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq, who took over power in a coup in 1977.

This incident is described in the first chapter of Steve Coll’s Pulitzer prize-winning book “Ghost Wars,” but it has otherwise largely fallen out of the collective consciousness of even those who closely follow the U.S.-Pakistan relationship, dwarfed by the other events that took place that year in the region: the Iranian revolution, the Iranian hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. But the incident had direct links with the Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis, and was also an indicator of the rising influence of the Jamaat in Pakistan and of Zia’s coming Islamization.

Brothers in arms

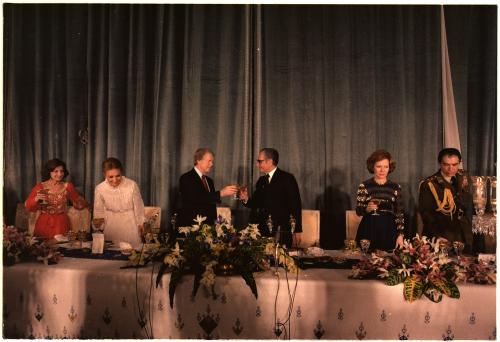

The siege on the U.S. embassy in Islamabad came a day after an attack by Islamist militants on the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Iran’s new supreme leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, publicly blamed America and Israel for the attack. Pakistani newspapers carried that accusation as news. Anti-American sentiment in Pakistan was running particularly high because the Carter administration cut off aid earlier that year over Pakistan’s construction of a uranium enrichment facility. Cue the Iranian revolution and then the hostage crisis, and Jamaat-affiliated students, always anti-American, were particularly emboldened. The Mecca mosque attack was the last straw.

In the end, the Pakistani army dispersed the rioters. The attack cost $20 million in damages; the protesters returned the hostage unharmed. Two of the attackers were killed in firing from the Pakistani side. That night, Zia told the country that no Americans or Israelis were involved in the Mecca attack. He also gently scolded the attackers in Islamabad, saying that while he understood “the anger and grief over this incident were quite natural,” this was not the way to react.

Khomeini praised the rioting in Islamabad. He declared it was a “great joy for us to learn of the uprising in Pakistan against the U.S.A. It is good news for our oppressed nation. Borders should not separate hearts.”

Khomeini praised the rioting in Islamabad. He declared it was a “great joy for us to learn of the uprising in Pakistan against the U.S.A. It is good news for our oppressed nation. Borders should not separate hearts.”

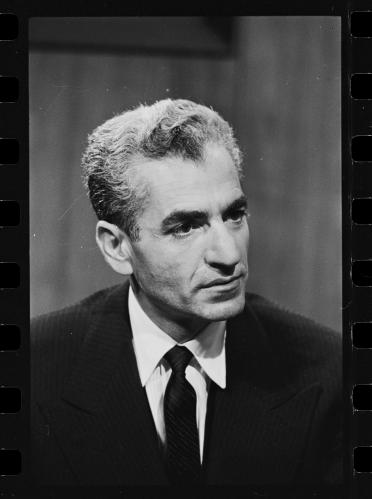

Zia pacified the U.S. government, expressing great regret over the loss of American life. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan the following month, and Zia’s signing on as a party with America and Saudi Arabia to train mujahideen for the war meant the beginning of a decade-long alliance between America and Pakistan; ironically, some of the Jamaat’s madrassas helped train the mujahideen, and some of those fighters were Jamaat members.

An emboldened Islamization

From 1977 to 1989, Zia engaged in a multi-faceted Islamization of Pakistan, and used the Jamaat-e-Islami to help him, especially in the early years. Though his reasons for this Islamization were political—he relied on Islam for legitimacy, as did many of Pakistan’s leaders—he was no doubt encouraged by the Islamic revolution in Iran. And though Pakistan did not become a theocracy like Iran—there was no centrally imposed, sectarian version of religion—in that decade Zia successfully “shariah-tized” aspects of Pakistan’s laws, emboldened its Islamist parties, and Islamized its curricula. His changes have proven all but impossible to reverse.

In 1979, Zia enforced Hudood laws—with shariah-like legislation—that in particular served as a blow to the status of women. The laws criminalized adultery and introduced draconian punishments such as stoning to death for adultery and chopping off hands for theft. That same year, he created “shariat benches” in the provincial high courts to rule on the repugnancy of Pakistan’s laws to the Quran and Sunnah (the body of Islamic practice based on the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings). In 1980, Zia also established a Federal Shariat Court, which could issue rulings that were mandatory.

In 1981, Zia’s University Grants Commission issued the following guidance to Pakistan Studies textbook authors: “To guide students towards the ultimate goal of Pakistan—the creation of a completely Islamized State.” The first chapter of these social studies textbooks was now titled the “ideology of Pakistan,” which, the textbooks said, was Islam. It was the Jamaat which coined the “ideology of Pakistan” term.

In 1984, Zia engaged in a referendum to extend his rule. He framed it a referendum on Islam, asking Pakistanis:

“Do you endorse the process initiated by General Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq, the President of Pakistan, for bringing the laws of Pakistan in conformity with the injunctions of Islam as laid down in the Holy Quran and Sunnah of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and for the preservation of the Islamic ideology of Pakistan, for the continuation and consolidation of that process, and for the smooth and orderly transfer of power to the elected representatives of the people?”

His government claimed that 98.5 percent of those who voted said yes.

And in 1986, Zia amended Pakistan’s blasphemy laws to make offences against the Prophet Muhammad punishable by death, setting in motion decades of violence over the issue. More than a thousand Pakistanis have been accused of blasphemy since the mid-1980s, and at least a few dozen killed in vigilante killings.

Zia’s Islamization and the Iranian revolution also helped stoke Sunni-Shiite sectarian tensions in Pakistan in the 1980s. Zia’s shariat benches were staffed with Sunni judges who favored Sunni legal interpretations; the madrassas that mushroomed in the 1980s, with Saudi aid, were Sunni. Meanwhile the man Zia had deposed, Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, was Shiite. In 1979, Zia had him hanged. All this stung Pakistan’s 20 percent Shiite minority; they were also emboldened by the revolution in Iran. The stage was set for Sunni-Shiite conflict.

Iran’s revolution, U.S.-Pakistan ties, and domestic politics in Pakistan

Ultimately, it was the most immediate and visible effect of the Iranian revolution in Pakistan, the November 1979 embassy siege in Islamabad, that had the shortest-term impact on Pakistan and on U.S.-Pakistan relations. It was Iran’s more subtle effect on Zia, on the Jamaat-e-Islami, and Sunni-Shiite sectarian tensions, that transformed its eastern neighbor, and defines it still.

Commentary

1979: Another embassy under siege

January 24, 2019