As the USS Carl Vinson concluded a week-long port call to Danang, Vietnam today, one can’t help but consider the contrast to not-too-distant memories from when both countries were locked in a long, bloody war. The USS Carl Vinson, home to 5,500 American sailors and 72 aircraft, is the first U.S. aircraft carrier to visit a Vietnamese port since the Vietnam War ended over four decades ago. Yet, while the visit may seem startling to some, it actually reflects longstanding trends in U.S.-Vietnam relations that have been building for over two decades—illustrated by diplomatic normalization in 1995, previous ship visits starting in 2003, and steady increases in maritime security cooperation over recent years. It also supplements Vietnam’s concurrent deepening in defense ties with other U.S. security partners in the region, including Japan and India.

In some ways, Vietnam is at the epicenter of broader developments in U.S. Asia policy and regional security cooperation generally. Under the rubric of its new “Indo-Pacific” strategy, the Trump administration is maintaining and enhancing Obama-era policies to expand bilateral relations with emerging partners in Asia, like Vietnam, and to encourage the development of security networks among like-minded countries—including U.S. allies and emerging partners—to address regional challenges like maritime security and counterterrorism. Sustained U.S. engagement has breathed new life into a quadrilateral security dialogue in the region, commonly known as the “Quad,” encompassing the United States, Japan, India, and Australia. All of these countries have stepped up defense cooperation with Vietnam in recent years.

The common concern propelling such security cooperation is China, and specifically its massive reclamation and militarization activities in the South China Sea. China’s maritime claims span Vietnam’s entire coastline, creating serious territorial disputes and overlapping claims between Beijing and Hanoi. This is part of a concerted island-building strategy to create “facts on the sea,” including airfields, maritime ports, and resupply facilities. In 2014, Hanoi was stunned when China National Petroleum Corporation moved an oil rig into waters off the Paracel Islands claimed by Vietnam. The move set off protests across Vietnam lasting for weeks, with angry Vietnamese protestors burning down Chinese businesses and forcing Beijing to extract thousands of its citizens fleeing the country. The China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) announced it was withdrawing the rig after two months.

The Vietnamese are realists in the face of these challenges, however, and understand they need a stable relationship with China due to their economic dependence and geographic position. At its core, Vietnamese foreign policy aims to balance China without provoking it. Consistent with this approach, Vietnam adheres to a “multi-directional” foreign policy doctrine rooted in “three no’s”: no foreign troops on Vietnamese soil, no allying with one country to counter another, and no military alliances with foreign powers. Since 2001, Hanoi has diversified its foreign relations and established comprehensive or strategic partnerships with 16 countries, including Japan, India, and Russia. It has even established a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership” with China, the highest-level category in Vietnam’s diplomatic pecking order.

Still, within this multidirectional approach, there has been a particularly noticeable uptick in Vietnam’s security cooperation with countries that share a common concern about China’s assertive maritime moves in the South China Sea. U.S.-Vietnam relations expanded quickly under the Obama administration. Highlights included the signing of an MOU on Defense Cooperation in 2011, establishment of a comprehensive partnership in 2013, and agreement on a Defense Relations Vision Statement in 2015. Washington also announced it would fully lift a longstanding lethal weapons ban on Vietnam during Obama’s visit to Vietnam in 2016, when the two countries outlined plans to expand maritime security cooperation, reflected in the delivery of a Hamilton-class cutter to the Vietnamese coast guard last year.

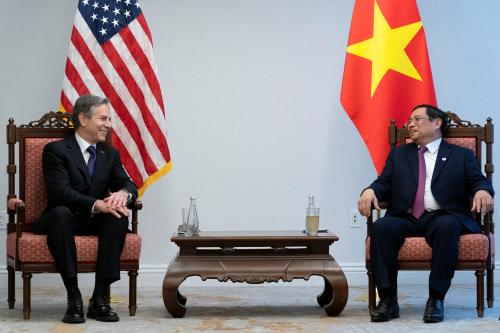

These trends have continued under the Trump administration. President Trump traveled to Vietnam for the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in November, making it the first Southeast Asian country he visited as president. While on a state visit hosted by President Tran Dai Quang in Hanoi, the two sides announced commercial agreements worth $12 billion and concluded the 2018-2020 Plan of Action for U.S.-Vietnam Defense Cooperation. Secretary of Defense James Mattis soon followed on Trump’s trip to Hanoi to meet with Vietnamese Defense Minister Ngo Xuan Lich. The two discussed regional security issues and pledged to deepen defense cooperation. They also confirmed plans for the USS Carl Vinson’s visit to Vietnam this month.

Significantly, Vietnam’s diversification efforts have not been limited to the United States. Japan is contributing to Vietnam’s defense capabilities by enhancing military exchanges and defense personnel interoperation. It also transferred six Coast Guard vessels to Vietnam in 2014 and pledged another six in 2017. Vietnam analyst Le Hong Hiep has reported that Japan will transfer two advanced radar satellites to Vietnam in 2018 as part of its official development assistance, noting that Hanoi is also mulling purchasing anti-submarine and surveillance aircraft from Japan. This equipment will expand Vietnam’s maritime domain awareness capabilities in the South China Sea.

Hanoi is expanding cooperation with India as well. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Hanoi in 2016, the two countries elevated their relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership, and Modi pledged $500 million in credit to upgrade Vietnamese defense capabilities. New Delhi also offers submarine training to the Vietnamese Navy, which is important because both countries use Russian-built subs. On top of defense cooperation, Vietnam has extended exploration rights to Indian state-run oil company Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) Videsh to mine the seabed in block 128, territorial waters that fall within China’s “nine-dash line.”

Vietnam’s expanding relations with these “Quad” countries have unfolded alongside growing divisions within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on how to cope with China’s rise and activities in the South China Sea in particular. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has taken a softer line toward Beijing while seeking greater economic support and investment from China, reversing the tougher maritime stance of his predecessor. Meanwhile, Vietnam is playing a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, it continues to challenge China’s maritime claims, while carrying on with its own reclamation efforts. On the other hand, it appears to have relented to Chinese pressure by backing off a recent oil exploration venture in the South China Sea last summer—in a deal involving the Spanish corporation Repsol—after Beijing is reported to have threatened to use force if the exploration continued.

Vietnam is mindful that China is economically powerful as well. China is Vietnam’s largest trading partner, accounting for nearly 30 percent of Vietnam’s imports and over 10 percent of its exports, and Beijing hasn’t hesitated to leverage its economic influence in the past. Keen to reduce its dependence on China, Hanoi is taking steps to diversify its economic relations by agreeing to a free trade agreement with the European Union, which will come into effect this year, and was highly motivated to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership in its original formulation involving the United States. It is among the 11 nations that just signed the revised and scaled-down version of the TPP, known as TPP11 or the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The U.S. withdrawal from TPP places limits on economic engagement with Vietnam, as member countries will benefit from the diminishing trade barriers rooted in this high standard agreement. But the bilateral relationship is broadening into new areas, evolving in a more strategic direction, and has significant upside potential as reflected in the USS Carl Vinson visit to Danang this week. The multifaceted nature of the U.S.-Vietnam partnership is also mirrored in Vietnam’s expanding relations with a growing number of other countries and security partners, spanning the entire Indo-Pacific, itself a reflection of a changing and dynamic region.

Commentary

As U.S. aircraft carrier departs Vietnam, what are the implications for regional security?

March 9, 2018