Last May, in Taiwan’s third peaceful transfer of power between elected leaders, then-President Ma Ying-jeou of the Kuomintang (KMT) ceded his position to then-opposition leader and today’s president Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). During her campaign and continuing to today, Tsai has not explicitly affirmed a core operating principle of Ma’s administration: conducting relations with Beijing on the basis of the “1992 consensus.” What is that consensus, and what might the shift portend for Taiwan’s future?

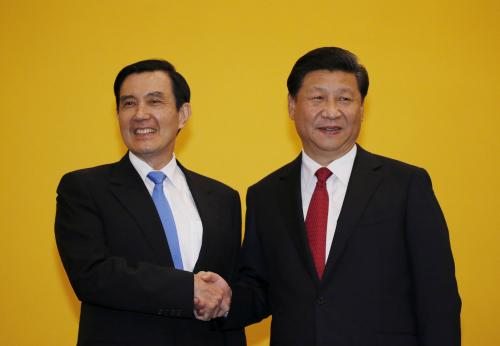

At an event co-hosted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Center for East Asia Policy Studies at Brookings on March 7, former President Ma outlined the history and practice of the One China principle, discussed his administration’s approach to the 1992 consensus and Beijing, and offered his own recommendations for the next stage of cross-Strait relations.

One China, unpacked

The People’s Republic of China currently has diplomatic relations with 173 countries; with 137 of them, it concluded joint communiqués at the time of establishing diplomatic relations. Of the 137 joint communiqués, 52 countries recognize that the People’s Republic of China has sovereignty over Taiwan; 29 countries—including the United States—use ambiguous language on whether Taiwan is a part of China; and the remaining 56 simply don’t mention Taiwan. President Ma highlighted these numbers to illustrate how wide-ranging the One China principle is practiced globally.

Ma expressed relief that President Trump confirmed the One China policy in his call with Xi Jinping, as this ambiguous U.S. policy has helped sustain cross-Strait stability. Although many in Taiwan were excited by the December news that then-President-elect Trump spoke with President Tsai over the phone, that sentiment soon subsided following Trump’s further comments on the One China policy and Beijing’s hardline reaction to the call. People in Taiwan don’t want to be bargaining chips in U.S.-China relations, so a return to business as usual was welcomed. Quoting his law professor at Harvard, Ma reminded the audience that Taiwan is the “most recognized, unrecognized government of the United States.”

Ma then discussed how the One China principle has been implemented in cross-Strait relations. People-to-people contact across the Strait restarted in the late 1980s, but under President Lee Teng-hui in 1992, Taiwan’s Strait Exchange Foundation (SEF) and China’s Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait (ARATS)—the two organizations that negotiate cross-Strait relations—met in Hong Kong. During the initial meeting in October 1992, no consensus was established, but a few weeks later, SEF sent a new proposal that called for both sides to insist on a One China principle, but defer the definition to each side. This “one China, respective interpretations” eventually became known as the 1992 consensus, and the foundation for the Ma administration’s relations with the mainland.

Fmr. #Taiwanese Pres. Ma Ying-jeou discusses the centrality of the #OneChinaPrinciple to cross-strait relations & #TaiwanFuture @BrookingsFP pic.twitter.com/EPSvpgjqVI

— Hunter Marston (@hmarston4) March 7, 2017

After DPP President Chen Shui-bian (2000 to 2008) applied a different interpretation of One China—one country on each side of the Strait—President Ma returned to the 1992 consensus upon entering office in 2008. He credited this policy shift for driving increased economic and cultural activity between the mainland and Taiwan. As he described, his aim was to build a bridge across the Strait that future leaders could then utilize, so long as they followed the prescribed “traffic regulations” (when asked later what these traffic rules entailed, he simply responded: “the 1992 consensus”).

The current stalemate and what’s next

What about the current stalemate in cross-Strait relations? Ma noted that President Tsai Ing-wen “repeatedly expressed her goodwill and sincerity in maintaining a stable and peaceful status quo. In doing so, she vowed to abide by the ROC constitution and the Mainland Relations Act.” And yet, because she hasn’t explicitly endorsed the 1992 consensus, Beijing has, once again, halted official communications. Ma posits that the current environment is reminiscent to the conditions during his presidential campaign ten years ago. The stalemate, he warned, could create challenges for Taiwan’s tourist industry and service exports, as well as Taiwan’s involvement in the international community.

Emphasizing that “it’s clear that rhetoric will not help, so we need concrete actions,” Ma then outlined steps that both sides could take to rebuild mutual trust. For instance, he noted Taiwan’s appeal to attend the 2017 World Health Assembly (WHA) and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) conferences, as they have in previous years. In a similar vein, he said that an important step to build Taiwan’s role in the international community is establishing a diplomatic truce, through which neither Beijing nor Taipei attempts to sway diplomatic relations from each other. Efforts to increase the number of mainland tourists and students in Taiwan and restore negotiations for the cross-Strait trade-in-goods agreement are two measures that can create economic opportunities in Taiwan. Beijing, however, has its own set of conditions that it seeks Taiwan to complete. They include Taiwan acknowledging that people on both sides of the Strait are all ethnic Chinese people of the Chinese nation (中華民族) and that cross-Strait relations are not international, but rather “special” relations (特別關係). And, of course, Beijing wants President Tsai to accept the 1992 consensus.

President Ma concluded by defending his cross-Strait policies and arguing that his acceptance of the 1992 consensus led to greater international cooperation for Taiwan. Further, while the 1992 consensus is ambiguous, he argued that its core connotation implicitly exists in the agreements other countries maintain with China. Since 70 percent of the countries that have communiqués with China also take a flexible stance towards Taiwan, that means—in his view—that they effectively practice the “one China, respective interpretations” version of the One China principle. That, in turn, has allowed them to maintain diplomatic relations with Beijing while also conducting substantive diplomacy with Taiwan.

Commentary

Former Taiwan president Ma on One China, the 1992 consensus, and Taiwan’s future

March 16, 2017